The entrepreneurs fixing Pakistan’s problems one start-up at a time

Making healthcare accessible for women and using video games to help children with special needs are among the new apps transforming the world’s fifth most populous country. Zlata Rodionova and Julia Hanne report

With his yellow backpack and Pakistani school uniform, Namir looks like a typical 11-year-old. He’s charming, lively and has a passion for video games. But the little boy also suffers from a brain injury and physical disability, as a result of being given the wrong injection to treat his meningitis as a child.

Disability remains heavily stigmatised in Pakistan, where 96 per cent of children with special needs are out of school and there is only one therapist for every 30,000 students. Rarely brought out into the public by their families, these youngsters often live in isolation, which worsens their condition.

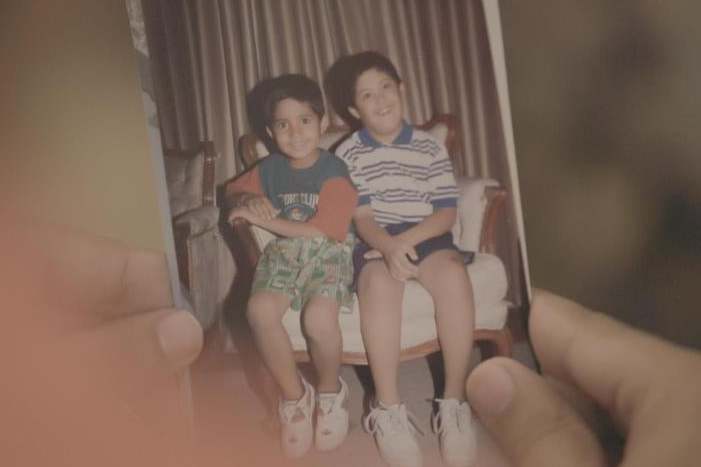

Dissatisfied with the complete lack of available treatment options, Muhammad Usman, whose elder brother suffers from Down’s syndrome, founded WonderTree – a start-up which introduces computer games to children with learning disabilities – in 2015. “One day, I saw my brother playing games on my console and he was really good at it. So I thought, why not do something different?”

He was quickly joined by his friend and fellow gamer Muhammad Waqas, who closed his corporate marketing firm to be part of WonderTree. The Karachi-based tech start-up now aims to “give back to the community” and help children with special needs by using interactive augmented reality and artificial intelligence games. Working in collaboration with special education teachers and psychologists, the start-up has already developed 17 games that are best suited for children with autism, Down’s syndrome and cerebral palsy, among other mental disabilities. Five more are due to be released by the end of the year.

“Children with special needs are not used to winning or to have things going their way. But in these games, they actually see themselves win, which really motivates them to repeat these exercises. In reality, their cognitive development is happening as they play,” Waqas says. Thanks to WonderTree’s technology, children with learning and motor disabilities are able to improve their motor skills as well as their cognitive and behavioural development.

The software also helps teachers track and document the performance of each child by using an in-built reporting system. “We can’t build special needs schools or increase the number of therapists, but what we can do is use technology to make treatment accessible, cheaper and effective,” Waqas says. By the end of this year, their games will be installed in over 100 special schools and 40 hospitals across 25 cities, with 40,000 children using the games.

Children with special needs are not used to winning or to have things going their way. But in these games, they actually see themselves win, which really motivates them to repeat these exercises. In reality, their cognitive development is happening as they play

Other countries have started to take notice and WonderTree is expanding to Qatar, the UAE and Europe in the coming year. “Whenever I hear success stories of a child progressing, I feel like my own brother is achieving something and it keeps me motivated to do more for these children,” Usman says.

WonderTree’s long-term global vision is to become a household name, “like a Google for parents with special needs children”.

Waqas and Usman are far from the only Pakistanis who have started their own tech business to take on the country’s most pressing development issues. “I think one of the great things about Pakistan is that there are a lot of challenges to start with. When you have to start with trying to find a lot of solutions to those challenges, you are training your brain to become a problem solver,” Saad Hamid, Google’s community manager, says.

Challenges abound in the world’s fifth most populous country. The education system is in crisis, with 22 million children out of school, while 50 per cent of its 200 million citizens lack access to healthcare. It also remains one of the riskiest places in the world for newborns, with one out of five never reaching their fifth birthday.

Start-up activity has surged in recent years as businesses have stepped in to address people’s unmet demands – and they are up for the challenge. “Their shared resilience is amazing, especially in this country, in the absence of any of the small business investment companies that you have in the west. They don’t have resources. And they’re still surviving,” Fasieh Mehta, planning and growth strategist of Pakistan’s first national incubation centre (NIC) in Islamabad, says.

At the NIC, where the youngest entrepreneur is a seven-year-old girl, 48 per cent of the entrepreneurs are women and start-ups have created over 2,386 jobs in the past two and a half years. Inclusivity and community-building are key guiding principles, with the centre being fully accessible to people with disabilities. The centre is also hosting drum circles, pitching sessions, a daycare centre for “mumpreneurs” and soon its first transgender entrepreneur.

Inspired by Silicon Valley, Pakistan’s aspiring entrepreneurs have ushered in a new business culture that is driven by ethical conduct and collaboration to overcome issues such as gender inequality and climate change, according to Yussuf Hussein, CEO of the government’s $75m (£58m) business investment fund Ignite. After 20 years of living in the US, where he ran a successful tech company, Hussein decided to pack his bags and return to Pakistan with the conviction that it could be one of the great tech investment opportunities of the next decade. He was one of many investors to do so.

The government has played a key role in building the momentum around technology and entrepreneurship; in 2017 it introduced a three-year tax relief for start-ups and created regulations to allow local venture capital firms and investors to establish a presence in Pakistan. Multinational companies like Microsoft have started to pay attention and are now working with the government on a policy framework to create a start-up hub in the country.

Other private sector firms and foreign governments have followed suit, setting up their own incubators including Google’s Nest i/o or UKAid’s five-year Spring Accelerator programme, managed by one of the British government’s largest private sector partners Palladium, which supports businesses in emerging markets like Pakistan. One of those businesses is the female-led health tech start-up Sehat Kahani, which uses an app to connect millions of female patients that lack healthcare with some of Pakistan’s 85,000 qualified female doctors, who are forced out of work after they get married.

You will not believe how many times I hear the sentence when we pitch to investors, ‘OK, you’re two female founders, but who’s the man behind the business?’

Women often struggle to get access to healthcare because they are not allowed to leave their homes or because of a lack of facilities in the area where they live. “Growing up as a female in Pakistan, we are told ‘there are only two noble and respectable professions for you: you can either be a doctor or a teacher’. My parents told me that I had to be a doctor. So for me, there was never another career option,” Dr Sara Saeed, co-founder of Sehat Kahani, says.

Parents are keen for female doctors to become their daughter-in-laws, but don’t want them to work. This explains why 70 per cent of the total medical workforce of Pakistan is made up of female doctors, but only 23 per cent practice. Once Saeed gave birth and moved to a new city following her wedding, the isolation she experienced from being unable to work made her slip into postnatal depression.

Having realised that a huge number of other “doctor brides” are going through the same experience, she created an app-based consultation service that brings these women back into the workforce by allowing them to work from home. Sehat Kahani has also started to enrol Pakistani doctor brides living in the US, Canada and the UK. The app either instantly connects female doctors directly with their patients or through nurses at one of their rural clinics, which also serve as community centres.

Saeed was joined by Dr Iffat Zafar, whose mother battled a life-long addiction to tranquilisers until she passed away earlier this year. “I think for the most part of her life, she struggled with getting access to the right healthcare. The need for businesses like ours is so immense because it’s not just my mother’s story, but also the story of so many women who live in isolation,” Zafar says.

For many of the women visiting Sehat Kahani’s clinics, it’s the first time they’ve seen a doctor. These clinics are meant to be one-stop-shops that resolve 80-90 per cent of their patients’ general and mental issues. In Pakistan, there are only 400 psychiatrists and psychologists in the entire country.

“We’ve been able to diagnose a 19-year-old with throat cancer only through clinical history and examination. We’ve also treated infertility in a woman who hadn’t had a baby in the last eight years and provided mental health care to patients suffering from schizophrenia,” Saeed says. In the next five years, Sehat Kahani plans to expand its doctor network from 1,500 to 5,000 and increase its reach from one to 14 million people. But despite their success, the two women routinely face scepticism.

You doubt yourself every other day but if you want to bring about change, it takes time. In the next 10 years, 40 to 50 per cent of the jobs that exist today will not even exist. We really wanted our country to be in that race

“You will not believe how many times I hear the sentence when we pitch to investors, ‘OK, you’re two female founders, but who’s the man behind the business?’” Saeed says. Scepticism is a common reaction other young entrepreneurs, not only women, have faced for forging a path into the unknown.

“When I used to say that we want to revolutionise education and introduce technology in Pakistan everyone used to laugh at me. So, whenever we ask for funding or mentorship we didn’t get a lot of results. But we never stopped because it wasn’t about the money,” Faisal Laghari, CEO of Pakistan’s first edtech start-up LearnOBots, says. His vision is to create the “makers and inventors of tomorrow, coming out of Pakistan” and to revolutionise the country’s education system.

According to Laghari, the biggest obstacle to incorporating technology into curriculums in Pakistan is the shortage of Stem teachers. To bridge this gap and to enable children from low-income communities to break into science careers, he developed the low-cost elearning platform RobotWala, which runs classes without a teacher and only requires a moderator or facilitator.

This has dramatically reduced the cost of providing Stem classes for schools to just $1 per month, enabling LearnOBots to reach hundreds of thousands of students across Pakistan and abroad, with the first pilot due to launch in South Africa this year. Requests are now coming in from 30 countries across the EU, as well as China, the UAE and Qatar. And LearnOBots has inspired over 30 other start-ups to improve Stem education in Pakistan.

While it would have taken five to 10 years to develop the platform, enrolling in UKAid’s SPRING Accelerator enabled him to bring the product to market within less than a year. Like many other start-up founders, Laghari broke with cultural tradition when, instead of following the path of graduating, starting a career and getting married, he left his well-paid job at a multinational company to found his own business, knowing he would have no salary in the foreseeable future. “You doubt yourself every other day but if you want to bring about change, it takes time,” Laghari says.

“In the next 10 years, 40 to 50 per cent of the jobs that exist today will not even exist. We really wanted our country to be in that race,” he adds.

Even though the start-up sector is booming, there are still many challenges ahead. The success of young Pakistani entrepreneurs is clouded by an ongoing parliamentary inquiry into UK aid to Pakistan. The result could lead to a significant cut in funds, potentially threatening the existence of some of the accelerator programmes in the country.

The absence of any investment in small business also makes the future of some of these companies uncertain. Meanwhile, power outages, which have plagued Pakistan for years, continue to cripple industries and small businesses alike.

But most of the founders take each day as it comes. Meht, from the NIC, says: “In Pakistan, instead of being in an economy or situation where all things are taken care of, you have to think of new challenges every day, which kind of helps these founders develop that ability to think very fast and really creatively. Their shared resilience is amazing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks