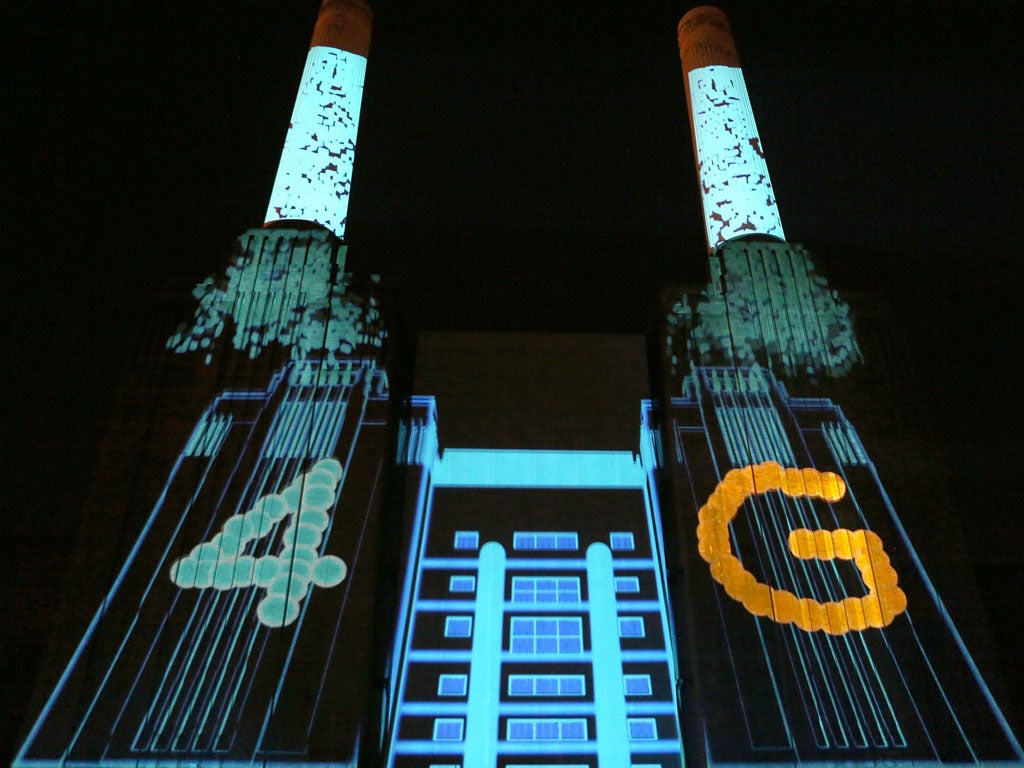

Really, who needs 4G?

David Phelan analyses the present and future of speedy mobile data

In the next few days the airwaves go on sale. Bidding begins for the auction of so much spectrum, as it’s called, it’ll increase the available airwaves by 75 per cent. This auction is for the frequencies that will underpin the next generation of mobile phones, tablets and more. The process will be powered by a complex and sophisticated piece of software designed specifically for the purpose.

But do we need it? What are the benefits? And should we care?

Well, for a start, we can have a clear idea of what’s coming because one network, EE, has already launched its 4G service. So: what was 4G set up to deliver and how’s it doing?

It came about because we mostly use smartphones now, supplementing calls and texts with obsessively browsing the internet, checking our email and – most of all – consuming apps on the go.

We were able to do this thanks to the last auction, for 3G frequencies. That led to Three launching the first 3G network 10 years ago (on 03/03/03) and other companies following suit. We were promised video calling (which came, but nobody really used it) and fast data connections. Only when the iPhone launched and added the word “apps” to our vocabulary did 3G data usage really take off. Suddenly, everyone wanted to have the latest currency conversions, stock prices and weather forecasts that speedy data made comfortable. Actually, almost nobody wanted those particular things, but they wanted to be able to get them, just in case.

And everyone certainly wanted to be able to tap an address into a maps app to see directions how to reach it. Or speak the name of a nearby restaurant to find its phone number, read reviews and check opening hours. Or use Augmented Reality – where digital effects are overlaid on top of the physical world the phone’s camera can see – to find the nearest Underground station in a deeply cool way.

Not to mention Facebook and Twitter posting and checking, iPlayer streaming and YouTube browsing.

All very well but the 3G networks have been creaking with the weight of data traffic for ages now. A YouTube clip uses hundreds of thousands times the amount of data a text message does. Hence the need for 4G, or 4G Long Term Evolution to give it its full name.

There are two bands of airwaves being auctioned in multiple lots. One is low frequency – 800MHz – and will be the most keenly fought over. Mobile signals travel further at lower frequencies so they can penetrate further into buildings and even underground. As Kester Mann, an analyst at CCS Insight points out, “One of the 800MHz lots will carry an obligation to provide mobile broadband coverage indoors to 98 per cent of the population by the end of 2017”. The other frequency is 2600MHz which won’t get inside buildings so easily but will still be in demand.

The 4G already available, from EE, is at a frequency in between, 1800MHz and came about because EE, forged from the union of Orange and T-Mobile had lots of spare capacity at this frequency. Enough to sell some to Three and launch its 4G service, called 4GEE, last November. And Phones4U has just announced it’ll use EE’s airwaves to provide its own virtual 4G network, called Life, in a few months’ time. So do you need it?

If you’ve ever spent time waiting for maps to download or a web page to build, you’ll know how frustrating this is. Apple’s iPhone has an excellent voice recognition service called Siri but it requires a data connection to work. If you’re dictating a text – way handier than tapping at the glass screen keyboard – you’ll have come across the familiar and all-too-infuriating three mauve dots which appear while the iPhone tries to parlay your spoken words into text. Even worse, when it just can’t do it, those dots wobble as if shaking their heads in sorrow.

This happens a lot on 3G connections. But if your EE phone says LTE in the top corner, everything flies. Dictation is converted to text often before you’ve taken the phone from your mouth to see what it’s doing. It’s spectacularly impressive, and since voice recognition, I predict, is going to be one of the technologies that comes of age this year, it will be increasingly useful.

Similarly, the pleasures of seeing Google searches populating the screen in a gnat’s crotchet or judder-free video streaming, are hard to exaggerate. To be clear, we’ve been here before – this is the speed and efficiency we were promised when 3G was launched, and my experiments are on a network which isn’t yet choked with users. Even so, the speed step-up does seem to be happening this time. Who knows, maybe we’ll take up video calling as well. Maybe not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks