Stargazing in September: A drop in the celestial sea

Nigel Henbest on why so many star patterns on view this month have watery themes; plus the two brightest planets vying for our attention

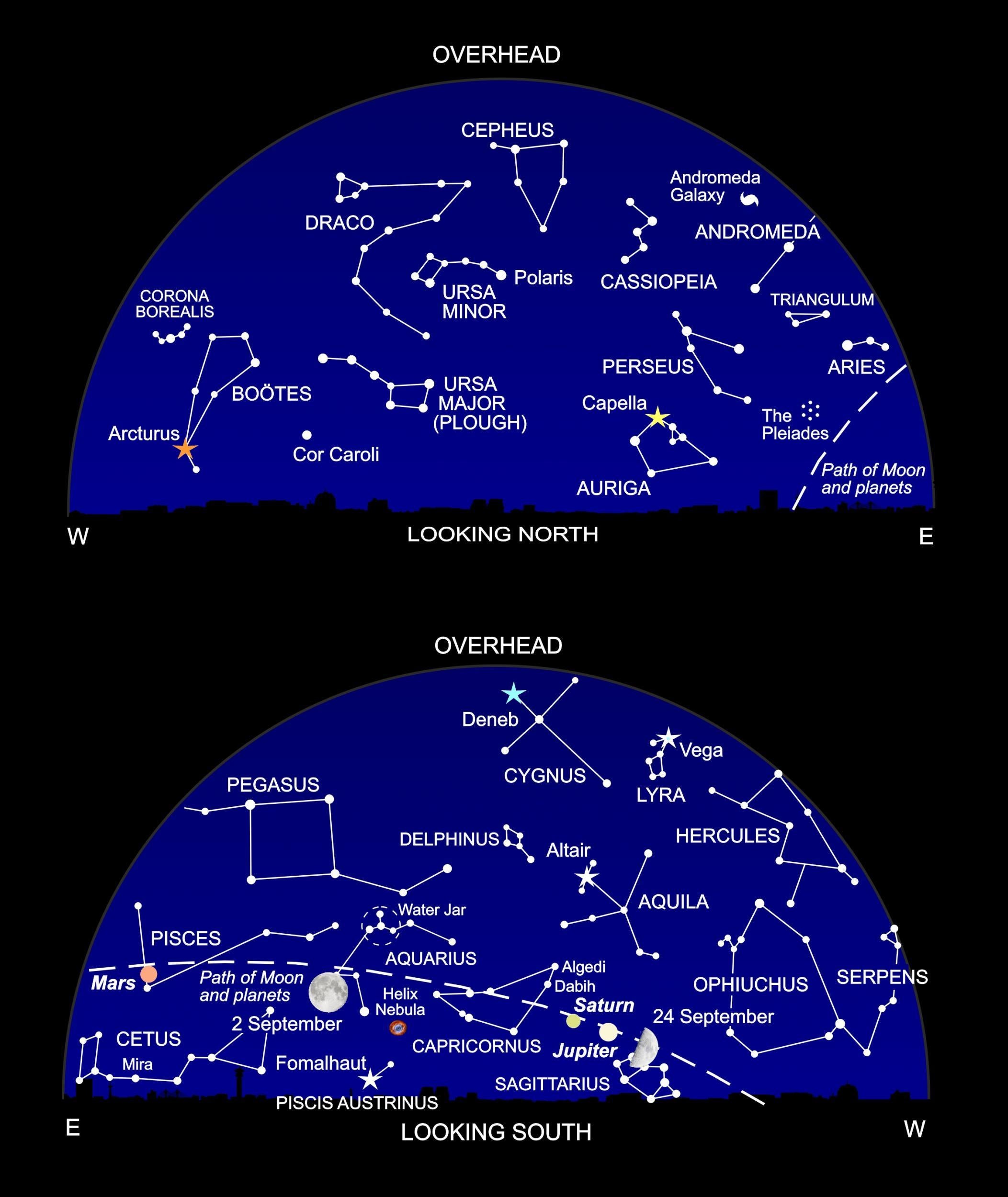

In the late evening, look around the horizon and you’ll spot two brilliant steady lights, brighter than anything bar the Moon. Don’t worry: it’s not an invasion of flying saucers. We’re being treated to two of the showiest planets rivalling one another for our attention. To the right we have giant planet Jupiter, and to the left Mars (more details below).

Between Mars and Jupiter, you’ll see only faint stars. But – amazingly – here we find some of the oldest constellations, drawn up by Bronze Age astronomers well before more familiar figures like Orion and the Plough. And all have a watery theme.

Right in the middle is a distinct pattern of four stars, a triangle centred on a fourth star, like the Mercedes-Benz logo. Marked on the chart as the Water Jar, it’s central to the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Bearer. The stars to the right mark his strong shoulders, while a stream of stars to the left depict a stream of water overflowing from his jar down to the horizon.

Ancient inscriptions from the Middle East name this constellation after the great Akkadian god Ea. He is depicted as far back as 2300BC, on an ancient stone seal found in southern Iraq, with streams of water gushing from his shoulders. This makes faint Aquarius one of the first constellations to be recorded, along with much more prominent Leo (the Lion) and Taurus (the Bull) which also appear on the Adda seal.

Mesopotamian civilisations divided the sky into three regions. The stars to the north belonged to Anu, the god of the heavens. Enlil, god of air and land, ruled the constellations around the equator of the sky. As god of the sea, Ea was in charge of the southern stars, and as a result the star patterns here have an aqueous theme.

The torrent from Aquarius’s Water Jar flows down to the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish), its mouth marked by brilliant Fomalhaut. To the right, you’ll find a large triangle of stars marking out the shape of Capricornus, the Sea Goat. This was another manifestation of Ea, the fish’s tail appropriate to his home in the ocean depths, while the goat’s head reflects his other role as the god of fertility.

To the left lie the big sprawling constellations of Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces, two fishes joined at their tails by a cord. And to the upper right you’ll find the compact star pattern of Delphinus (the Dolphin), four stars marking its body and one its tail as the playful cetacean leaps above the other maritime constellations.

For all this fascinating history, I’m afraid there aren’t many brilliant sky sights in the celestial sea. First, check out Mira, a star in Cetus that varies in brightness over the course of about a year as it swells and shrinks: at the moment, you can make it out with the naked eye but in a few months you’ll need a telescope to see it at all.

Look closely at Algedi, in Capricornus, and you’ll see it’s actually a double star: a telescope reveals that each of these components is itself a close pair of stars. A pair of binoculars reveals that nearby Dabih is a glorious double star, its components sparkling in yellow and blue.

Stealing the show, though, is the magnificent Helix Nebula in Aquarius, a multicoloured shell of gas puffed out by a dying star. It’s wonderful in long-exposure photographs, though you’ll need dark skies and a good pair of binoculars to catch it for yourself.

What’s Up

Let’s start with those brilliant planets. To the southwest, we have Jupiter, the giant of the planets. It’s eleven times wider than the Earth, and so capacious that you could fit all the other planets inside Jupiter – and still have room to spare.

The fainter “star” immediately to the left of Jupiter is another giant world. Saturn is 95 times heavier than the Earth, but it’s made of gas so tenuous that Saturn would float on water, if you could find an ocean big enough. The Moon passes near Jupiter on 24 September, and Saturn the following night.

Over in the east, competing with Jupiter for our attention, lies the Red Planet, Mars – actually more of an ochre-coloured world. On 5 September, you’ll find the Moon close by. Though Mars is tiny compared with Jupiter – just half the diameter of the Earth – we are approaching it so closely that by the end of this month it will equal Jupiter’s brilliance.

If you’re an early bird, you’re in for a true planetary show-stopper. Venus is rising in the east around 2.30am, its superlative luminosity putting even Mars and Jupiter to shame. Set your alarm for 14 September, around 5am, to see the wonderful sight of the Morning Star immediately below the crescent Moon. Aim binoculars or a small telescope at them, and between the Moon and Venus you make out a swarm of faint stars: it’s the Praesepe star cluster, also name – more poetically – as the Beehive.

Diary

5 September: Moon near Mars

10 September, 10.25am: Last Quarter Moon near Aldebaran

14 September (am): Moon near Venus

17 September, 12.00pm: New Moon

22 September, 2.30pm: Autumn equinox; Moon near Antares

24 September, 2.55am: First Quarter Moon near Jupiter

25 September: Moon near Saturn

Just published: Philip’s 2021 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky next year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks