2016: a tumultuous game-changer

For some, the year just gone was devoid of hope, for others it was the year of Hope Not Hate. Whatever your position, it was a year when norms and conventions were turned on their head

On Radio 4’s Today programme in the week before Christmas, four acclaimed historians were each briefed to place the tumultuous events of 2016 in context by selecting a year they considered so significant it stood out as a game-changer in history.

Bizarrely, one professor chose 1420, the year of The Treaty of Troyes, when the kingdoms of England and France were designed to become one (the plan collapsed two years later when Henry V died earlier than envisaged). Another expert chose 1066, when a relatively insignificant feudal kingdom called England was invaded by a Norman duke from across the sea.

Perhaps more conventionally, the others chose 1914, which triggered so many decades of death and fear; and 1989, when the fall of the Berlin Wall ended a Cold War and ushered in not only philosophical predictions of the “end of history”, but also a period when the tectonic plates of geopolitics genuinely shifted.

The year 1989 was also one that, after so long, filled people with hope.

For many, 2016 was a year in which the reservoirs of hope began to dry.

Some of the extraordinary events were on the cards.

The Independent’s editorial column on New Year’s Day this year highlighted some of the possibilities. We wrote that while it was wise not to be confident in predicting the future, “some events are easier to be definite about, and the importance of them – Britain’s place in Europe, and the unity of the United Kingdom itself, may well be decided in 2016”.

We said David Cameron’s “flippant remark that he cared ‘1,000 times more’ about the union of England and Scotland than the EU will be seen for what it is: a reflection of a careless, shallow politician willing to put the future prosperity of this country at risk to satisfy the emotional spasms of his backbenchers”.

“Never has so much been gambled for so little,” we warned.

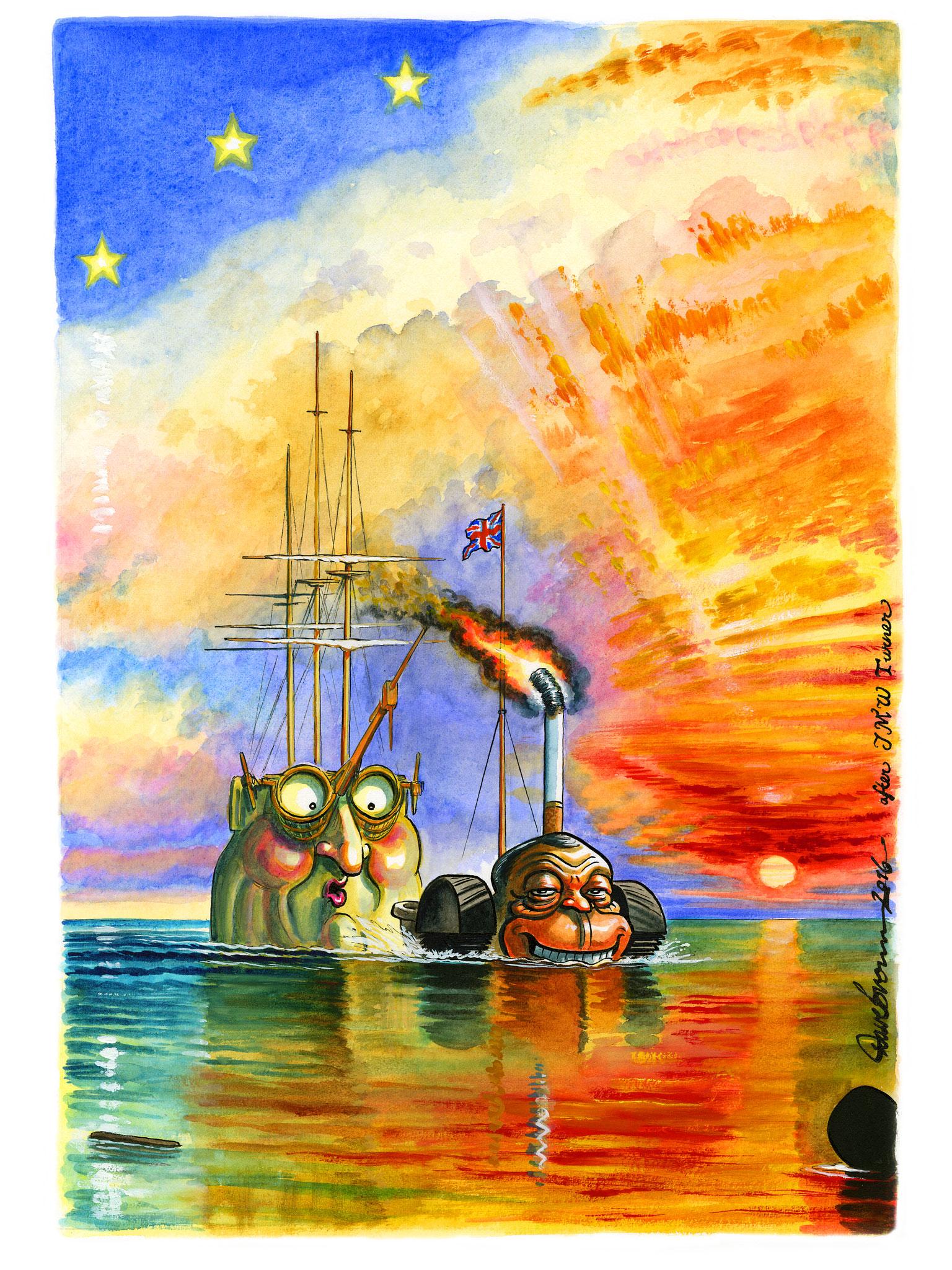

And on 23 June, largely due to a disconnect between London and the rest of England and Wales, he lost his gamble. Six months on – and after a disgraceful abuse of the honours system on his way out of Downing Street – it is perhaps a tragic measure of his place in history that Mr Cameron, 50, is so regarded as an irrelevant yesterday’s man who spectacularly failed to see the coming anti-establishment backlash.

His is likely to be a long road towards statesman status.

For Barack Obama, however, he might well look back at 2016 as the year in which his stature grew and his reputation was cemented, not necessarily by what he did, but by how half his nation took its own gamble.

Eight years after entering the White House on an evangelical message of hope, the Chicago showman is preparing to leave Washington to a man he despises in Donald Trump – and to deafening calls in some quarters for him not to go.

To misquote Shakespeare: Nothing in his presidency became him like the leaving of it.

Who would have thought it? Not us. On 1 January, we wrote this about US politics for the year ahead: “Not much more heartening is the race for the White House in the US. The appalling Donald Trump is still in the running for the Republican nomination – though his offensive, childish remarks about Mexicans seem guaranteed to deny him the presidency.”

But we added: “Whoever wins that contest will face some familiar challenges: trying to turn back Isis terror; making peace in Syria; repairing relations with Russia while protecting Ukraine; rebalancing the global economy; and – all too easily neglected – helping lead efforts to slow global climate change.”

And if they are the criteria for success, it could explain why President-elect Trump is – as offensive as it seems – the symbol of hope for millions.

While 2016 is unlikely to be seen as a year in which Islamist extremism had its greatest impact – 9/11 in 2001, 7/7 in 2005 and the Paris attacks of 2015 were more significant – atrocities in Belgium, France and Germany have arguably taken a more frightening turn.

In March, 22 innocents were murdered by explosions in Brussels. Four months later, jihadis slit the throat of a priest in Normandy, and ploughed a lorry into the packed promenade in Nice, killing 86. The same month, there were further attacks in Germany, where this week another truck was driven at speed into a Christmas market in Berlin: 12 lives were taken.

With every attack, the divisive determination of far right “populists” across Europe and the US deepened. Some believe it helped fuel Brexit and drive Trump to power.

Many mocked the Putin/Trump mutual admiration society this year, but given how Russian military intervention in Syria saw Bashar al-Assad reap its returns in 2016, others feel it could be decisive in dealing with Isis.

How they deal with climate change is more questionable. After the highs of 2015, this year proved disappointing in that fight. In September, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere moved above the landmark figure of 400 parts per million for the foreseeable future.

While the Paris Agreement on climate change at the end of last year had raised hopes, the follow-up Marrakesh summit was dubbed an “extreme disappointment” by campaigners.

Mr Trump is a climate-change denier and has pledged to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement.

But 2016 also saw many triumphs and justice prevail.

The campaigning families for the 96 killed in the 1989 Hillsborough disaster were finally given the verdict they demanded in April: their loved ones were unlawfully killed. The subsequent emotional reaction in Parliament was described as the “Commons at its best”.

In football, there was another happy ending as Leicester City, managed by the lovable “Tinkerman”, Claudio Ranieri, secured the Premier League title against all the odds. At the Rio Olympics, Team GB had another record Games, while Andy Murray cemented his reputation as the country’s greatest active sportsman by winning Wimbledon again and ending the year as World No 1.

And, of course, it is customary in media reviews of the year to note the passing of notables as neat and somewhat nostalgic chronological bookends.

David Bowie, Alan Rickman, Terry Wogan, Harper Lee, Ronnie Corbett, David Gest, Prince, Victoria Wood, Muhammad Ali, Caroline Aherne, Gene Wilder, Andrew Sachs, Fidel Castro, Leonard Cohen, AA Gill: all of them – even Cold War warrior Castro – were curious throwbacks to more straightforward times.

And then there was MP Jo Cox, murdered at the hands of neo-Nazi Thomas Mair as she attended her constituency surgery on 16 June. In any other year, her death – and the photograph of her standing on her east London houseboat by Tower Bridge – would be the enduring image.

That that instead falls to a grinning Nigel Farage standing next to Donald Trump in a gold-plated Manhattan lift would no doubt have appalled her.

Two men became history makers. A week after her death, Mr Farage saw his cherished ambition fulfilled with the vote to leave the European Union. He changed the course of British history. The frenzy of the next several weeks were unprecedented: the resignation of David Cameron; the feud between Michael Gove and Boris Johnson; the implosion of Andrea Leadsom; the arrival of Theresa May at No 10; and the failed coups in Turkey and against Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader.

Will 2016 be seen as the year of the grassroots backlash? Or when the far right began to extend its stride? Jo Cox’s widower, Brendan Cox, has continued her campaigning with Hope Not Hate. Most people will surely dream that those three words become the legacy of 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks