Andrew Adonis: ‘The prosperity of the North is not founded on the suppression of London’

London should heed the warning of the fall of Rome to continue to maintain its place as the ‘capital of Europe’

To the Guildhall in the City on Tuesday to hear Andrew Adonis address the Strand Group on what London needs to do to remain the greatest city in the world. Against the prevailing wail about London’s dominance of the UK, he seeks to boost London further and spread its success to the rest of the country.

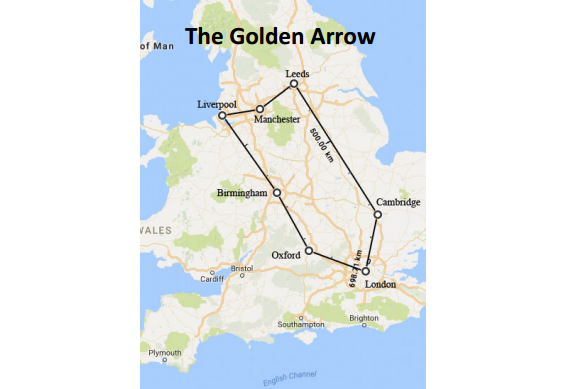

The main thing is greater connectivity with other cities in what he calls the Golden Arrow: Oxford, Cambridge, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds. This makes me uneasy. Adonis’s map reminds me of the one of greater Tokyo superimposed on England (below), and seems to be proposing that most of England should become an island megalopolis – a word Adonis himself uses – off the coast of Europe.

As you might expect, however, Adonis makes a good case. His energy and capacity to generate ideas are extraordinary. Where most ministers leave no mark, he left two substantial legacies: academy schools and the High Speed 2 railway. Now he is not just a visiting professor at King’s College London, where the Strand Group under Jon Davis is based, but chair of the National Infrastructure Commission and a hypercharged campaigner against Brexit.

Some of the objections to the Golden Arrow idea are the same as those to HS2: that it will draw even more economic activity from the rest of the country to the capital. As Sir Richard Mottram, former top civil servant at the Transport Department, said in the Q&A after Adonis’s lecture, the arrow points towards London. That’s the trouble with clever graphic devices: Adonis was forced to insist, against the visual cue, that it pointed both ways.

But his essential argument in the lecture – the full text of which is here – is that suppressing London does not raise up the rest of the nation:

The 40 years until the 1980s were particularly bad for London because of the mistaken policy of industrial relocation: a policy of deliberately trying to move jobs, businesses, indeed whole industries, out of the capital, because it was supposedly overheated, seeking to locate them instead in the Midlands and the North. The 1966 selective employment tax introduced a levy on service jobs – which of course were disproportionately in London and the south – intended to subsidise manufacturing jobs, which were assumed to be the forte of the Midlands, the North and Scotland. The London Government Act of 1963 went as far as to make it illegal for the GLC to advertise industrial opportunities in London. This, by the way, is one of the most amazingly discriminatory British legislative provisions I have ever come across: the 1963 Act said: ‘Nothing shall authorise the Greater London Council to give publicity in the United Kingdom, whether by advertising or otherwise, to the commercial and industrial advantages of Greater London; and nothing shall authorise the publication of any advertisement, or the establishment or maintenance of office accommodation, by the Greater London Council in any place outside the United Kingdom.’

The effect? London’s population fell sharply; unemployment rocketed, public services decayed – the London Underground in the 1970s looked as if it had witnessed the fall of Rome – and swathes of Inner London became ghettos of poverty, crime and hopelessness. But the same happened in the cities of the Midlands and the North too. Except that they got it even worse: the population of Liverpool halved in the 60 years after 1937. What we learned then was that less London does not mean more Liverpool, or any other city well beyond London. The prosperity of the North is not founded on the suppression of the South; on the contrary, the prosperity of London breeds the prosperity of Liverpool.

There is obviously a lot of truth in that, although Adonis himself has proposed moving at least the House of Lords out of London, if not the House of Commons too. And he does recognise the importance of east-west links across the spine of the arrow. He is an enthusiast for the Oxford-Milton Keynes-Cambridge line, and said of the Trans-Pennine Express, which takes an hour to go 40 miles, “That’s as much of an offence against the Trade Descriptions Act as my own name.”

Another feature of his Golden Arrow plan is that it is entirely English. Indeed, he closed his speech with a pretty graphic showing the distances between the five largest cities in the US, China, Japan, Germany, France and not the UK but England. Because if you put Glasgow and Edinburgh in it would have thrown out the neat progression towards the shape he had in mind.

Adonis’s vision does not even extend to the North-East of England. Indeed, he chastised the leaders of Newcastle, Middlesbrough and Durham for failing to appreciate the go-ahead qualities of directly elected mayors. But these were mostly rejected in local referendums until they were finally imposed elsewhere – an example of that oxymoron, centralised devolution – by David Cameron and George Osborne.

But he does make a powerful point about the failure of past attempts to push economic activity out of London and the South-East. The wonderful thing about Andrew Adonis is that, agree or disagree, he makes you think.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks