Modern cartoonists can still learn from the famous James Gillray – that’s why I’ve chosen to honour him

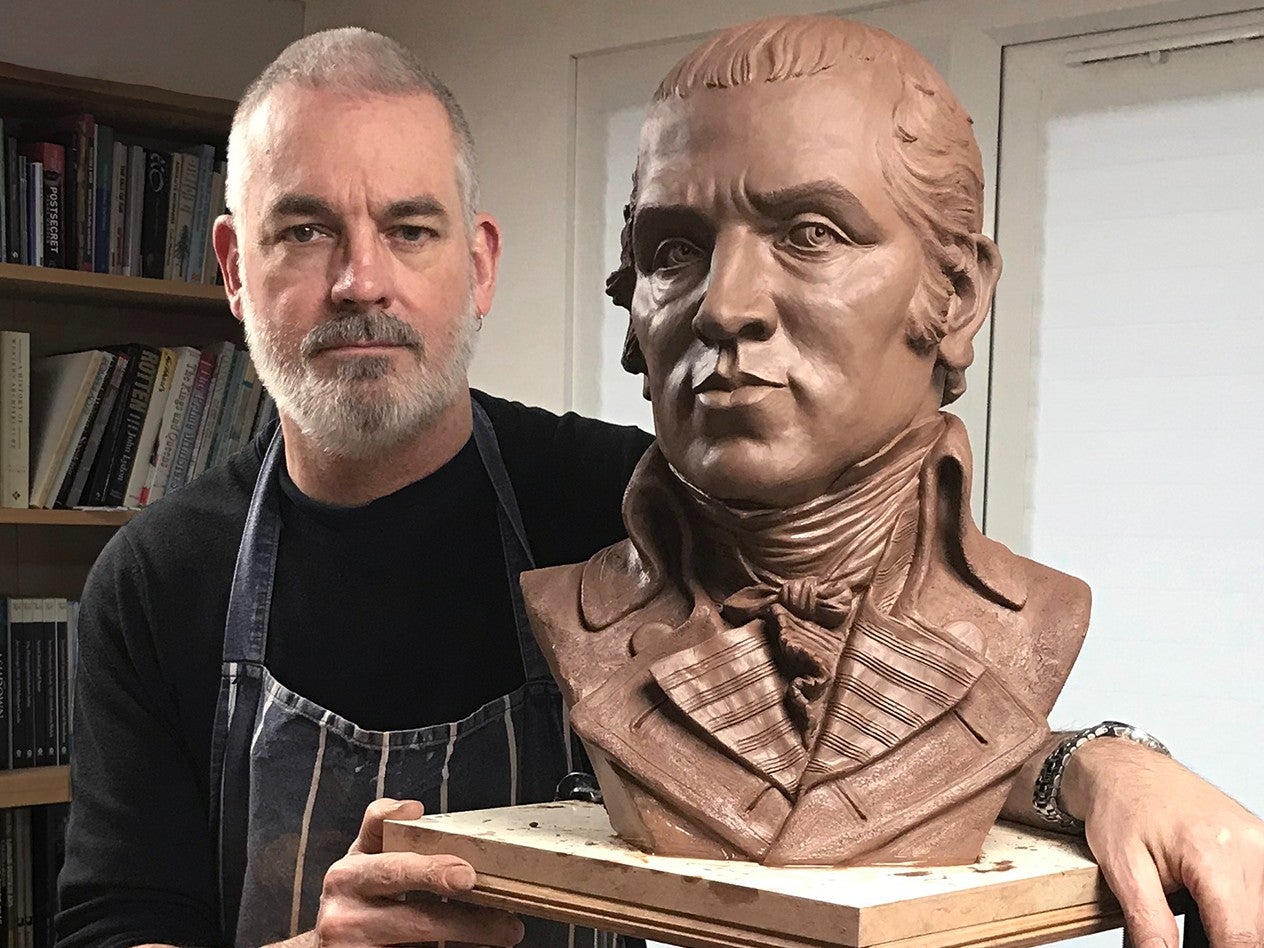

Gillray was not just one of the greatest satirical cartoonists to have lived, but one of Britain’s greatest artists in any genre. I hope my portrait bust does him sufficient justice, writes Dave Brown

If Hogarth was the grandfather of the modern cartoon, You were its father…"

so wrote the cartoonist David Low in 1943, addressing his 18th century predecessor James Gillray.

Born in 1756, Gillray set the template for the modern political cartoon. He combined the old tradition of the political print with the more modern art of personal caricature, his savage humour and supreme draughtsmanship making him the unrivalled visual satirist of the day. In The Plumb-Pudding in Danger he created arguably the greatest, and certainly the most pastiched, example of the form. For many contemporary political cartoonists he is a direct influence, but all cartoonists are indebted to him.

A little of that debt has recently been repaid. Gillray’s gravestone in St James’s churchyard, Piccadilly, had become badly worn and cracked, but was replaced this week with a new stone, funded by an auction of original artwork donated by today’s cartoonists.

Gillray is, in my opinion, not simply one of the greatest satirical cartoonists to have lived, but one of Britain’s greatest artists in any genre. His are the footsteps the rest of us walk in, the shoulders we stand on, the metaphors we still steal.

Gillray stood out from his contemporaries due to his outstanding visual inventiveness, but also the sophistication and innovation of his printmaking technique. His prints were known and admired by Goya and David, both artists borrowing from them in compositions of their own. One German journalist claimed Gillray was "the foremost living artist in the whole of Europe", while Napoleon allegedly remarked that Gillray’s depictions of him "did more damage than a dozen generals" (indeed our whole image of ‘little Boney’, and indirectly the Napoleon complex, are derived from Gillray’s depiction of him as a Lilliputian figure. When in fact Bonaparte was of average height for the age).

Despite the savagery with which Gillray often depicted his those he drew, politicians well understood that to be portrayed in his cartoons was a mark of their personal fame. George Canning was so keen to have his emergence onto the political scene "marked" by Gillray that he had an intermediary solicit the cartoonist and attempt to engineer "chance" encounters between them. Yet when Canning did finally achieve his goal it was merely as a corpse hanging from a lamppost amid the imagined horrors of a French invasion.

However, despite such acclaim in his lifetime, in the first anthology of Gillray's work, published three years after his death, the editor wrote: "It is a scandal upon all the cold-hearted scribblers in the land to allow such a genius as Gillray to go to the grave unnoticed".

Gillray’s antecedent in satirical print making, William Hogarth, is known to us from various self-portraits, a bust "from the life", a statue on the façade of the Victoria and Albert Museum and a more recent life-size bronze in Chiswick High Road. William Blake, another visionary print-maker and Gillray’s fellow student at the Royal Academy schools, commands both a small bas relief in St Paul’s and a large bronze bust by Epstein in Westminster Abbey. But of Gillray we have only one verified contemporary likeness, his self-portrait miniature, painted on ivory, measuring 3” × 2 1/2”.

According to contemporary accounts Gillray was a modest man, however it seemed to me that a simple gravestone and an ivory miniature were scarcely sufficient memorials for such a colossus. There are no blue plaques (the shop in St James’s, belonging to Hannah Humphrey, where he lived and worked, and where his prints were displayed, being long gone), and there are no statues… something I set out to rectify!

Without funding or a site to erect it, a full length statue was out of the question, but I could make a portrait bust. My preference in making a sculptural portrait would be to work from a live model and be able to take direct measurements of the head and its features. Second choice would be to work from an array of photos, showing every angle of the subject. However with Gillray all I had to work with was the one self-portrait. That portrait demonstrates that he was a skillful and adept miniaturist, detailing the short fringe brushed forward to conceal a receding hairline, and the heavy brow and prominent lower lip noted in contemporary descriptions.

So although the miniature also exhibits some stylistic traits common in neoclassical portraiture, we may assume he did not overly flatter himself, and that it is a reasonably true and honest likeness. However, it being the only likeness, proved to be both a blessing and a curse. As long as I captured the look of the portrait, when the sculpture was viewed from the same angle, there could be no other evidence to say I’d failed to achieve a likeness. But by the same token, there was nothing else for me to call on in trying to create a convincing three-dimensional image.

My partner helped solve this conundrum when she looked at the Gillray miniature and said: "he looks like Ronnie O’Sullivan!". I googled pictures of the snooker player, and it was true, the hair style was different of course, but the eyelids, the nose, the mouth, the general shape of the head were a match (I believe they could have been separated at birth, the 200 year age gap notwithstanding!). So armed with an 18th century portrait and some 21st century photos I began modelling the head in clay.

Although I was attempting to produce a contemporary artwork I also wanted the piece to reference neo-classical portrait sculpture, as though to some degree it was filling a gap, correcting the "absence" of an 18th century bust of Gillray.

I researched the work of Joseph Nollekens, whose sitters included two of Gillray’s famous victims Pitt and Fox, but also figures from the arts including Dr Samuel Johnson, Richard Brinley Sheridan, and David Garrick. Nollekens tended to portray his subjects in quasi-classical dress, but this pose of appearing as a noble Athenian or Roman senator seemed far too pretentious to apply to Gillray.

The French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon provided a better point of reference. His canonical portraits of the leaders of the American revolution mostly wear contemporary dress, no doubt a deliberate attempt to present a more egalitarian appearance. His bust of Benjamin Franklin, with its sideways glance and hint of movement in the mouth also suggested ways I might approach Gillray’s character. In Gillray’s self-portrait he is obviously studying himself in the mirror, but I thought that reproducing this sideways look might also suggest a somewhat sly scrutiny, as though in observation of one of his subjects.

Also by sculpting a slight pull in the muscle at the corner of the mouth I hoped to suggest the beginning of a sardonic smile. Whilst these are obviously things I am reading into, or imposing on Gillray, they do seem appropriate. This is what I see in Gillray’s self-portrait, moderated by what I know of his character and work, and of course, all portraits, whether from life or from a distance of 200 years, are to some extent a projection of the artist’s character onto the sitter.

When the clay modelling was complete the work was transported to the Bronze Age London foundry in Limehouse for moulding and casting. Despite the presence of a few modern materials, the lost-wax process of casting in bronze is still one the ancient Greeks, the artists of the Renaissance or the 18th Century sculptors Nollekens and Houdon would be familiar with. The work unveiled at the Cartoon Museum is the first casting, number one in what will be a limited edition of seven for sale.

I believe political satire is an essential correlative to a functioning democracy, so I should love to see a statue of Gillray in Parliament Square. To make room for him we could perhaps pull down a politician or two, starting perhaps with Canning.

Just as people who hunger for power are the last we should trust to wield it, perhaps people so desperate to be immortalised in art are the last we should erect monuments to. How much better to memorialise modest Gillray; from a plinth in the square he could cast a critical eye over both Lords and Commons, his etching needle poised to prick their pomposity.

If someone would care to petition parliament, I’m certainly available to make it, but until then I offer this portrait bust… the father of political cartooning by one of its b*****d offspring!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks