Charles Manson got under the skin of America – and the scary truth is that someone could easily do it again

His oft-quoted words, given in evidence during his trial, seem clichéd now and yet there is a resonance in spite of everything: 'My father is your system ... I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you.' It is the soundbite that every rebel dreamt of delivering

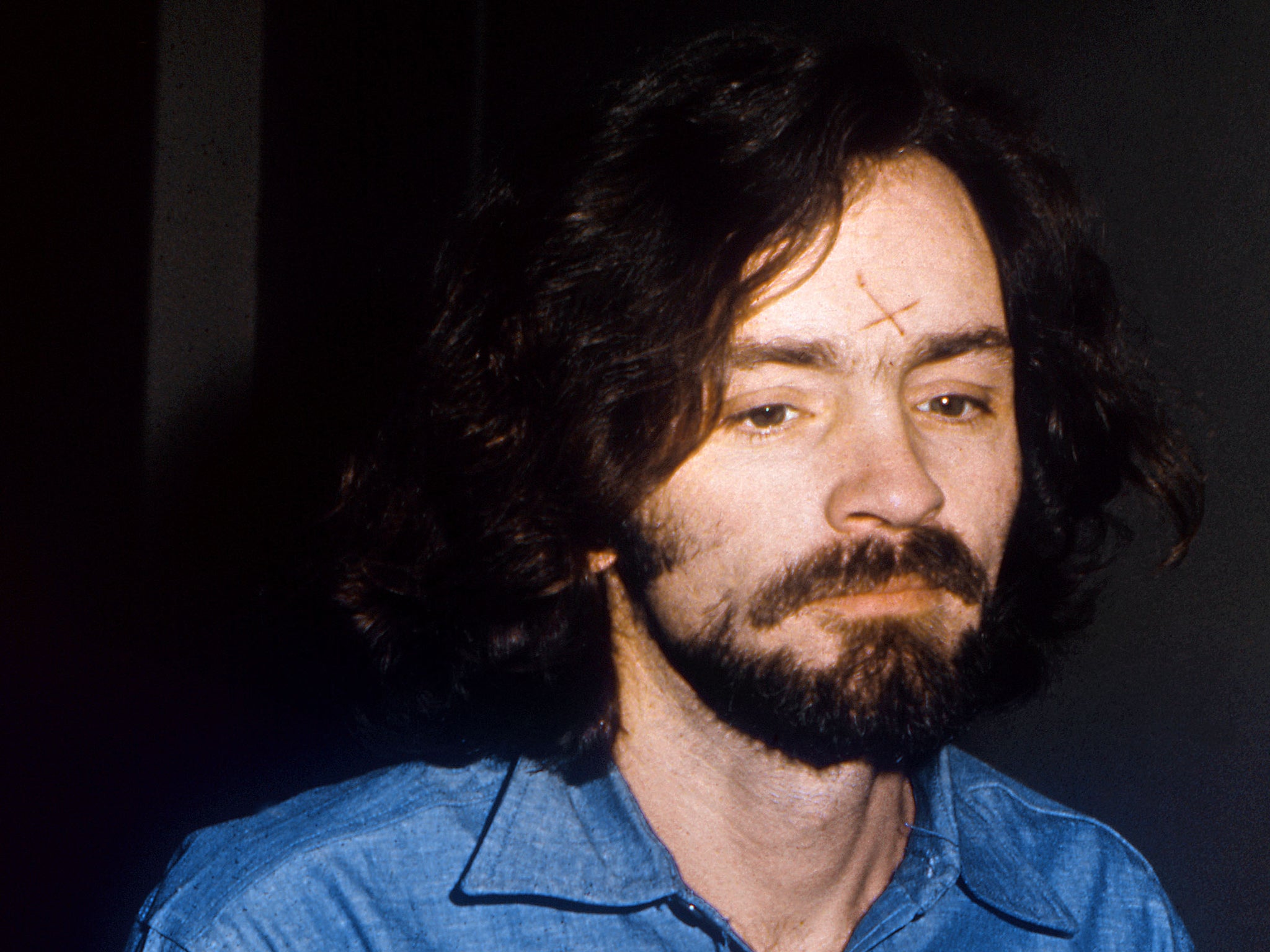

Charles Manson found an unsettling but lasting place in the cultural discourse of modern America.

The brutal crimes committed by his “Family”, on Manson’s orders in 1969, shocked the nation and the world. In the years that followed, the actions of his cult came to be seen as a violent denouement to the decade of free love, hippies and mind-bending drugs.

Manson’s link to the Beach Boys, via a fairly brief friendship with drummer Dennis Wilson, helped to round out the narrative – the criminal and cult on the one hand, the all-American close harmony group on the other: both very different products of the same counter-cultural revolution.

By all accounts Manson had an extraordinary hold over his followers, which was not solely the consequence of heavy LSD use. Despite his own modest education and a background rooted in poverty and unhappiness, he convinced dozens of people to join his Family and to buy into his beliefs about a coming race war that would end with his leadership of a new world order.

His disciples – many of them young, middle-class women – likened him to Jesus Christ and ultimately did his bidding in the most appalling way, murdering at least nine innocent people at Manson’s request.

Throughout the nearly five decades since those frenzied killings, Manson was arguably the most notorious prisoner in the world. Answers have been sought to the way he was able to influence his followers to carry out such horrors. Tomes have been written on the way his group was inspired by the popular culture of the times; and how the Family’s desecration of the Sixties golden era changed America for good.

Manson’s daily life in prison has been the subject of enduring interest too – especially the romances with women seemingly entranced by this would-be Messiah, even from behind bars. His death, perhaps inevitably, has dominated the news agenda.

At times, the fascination with Manson has leaned towards fetishisation. Marilyn Manson borrowed the cult leader’s surname; Kasabian were named after Linda Kasabian, a former member of the Manson Family. The media has thirsted for details of his life both before and after his incarceration.

To some Manson embodied evil, while to others he simply showed up 1960s hippiedom for what it was – a drug and ego-fuelled sham. But for a few who saw themselves being drowned in the mainstream, Manson could be regarded as something of a hero – an icon for the outsider, a rebel against the establishment.

Arguably the endless theorising was a self-fulfilling prophecy: Manson became a pop-cultural star because journalists asked how he became one. Yet that does not explain on its own the degree to which he got under the skin of America; how he forced many Americans to question themselves and their society.

Indeed, one imagines that was precisely what Manson had always hoped to achieve. His oft-quoted words, given in evidence during his trial, seem clichéd now and yet there is a resonance in spite of everything: “My father is your system ... I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you.” It is the soundbite that every rebel dreamt of delivering.

The paradox today is that America is in the grip of another kind dissident in Donald Trump, who came to power precisely on the back of the feelings of disenchantment and disengagement that echo through Manson’s statements. It would be a stretch to make a direct comparison between these two charismatic men, whose backgrounds could not be more different. Yet just as Manson won the loyalty of his followers and brought freewheeling Sixties America to a juddering halt, so Trump, by inspiring millions of voters, has had the same effect on the political consensus that had dominated the US for a lifetime.

The difference is that Trump had the money, and now has the position, to make a lawful – if controversial – difference. Manson’s attempt to change the world was manifested in a handful of grisly murders.

Manson’s death will not bring an end to the debates about his life and crimes. Nor should it stop the questions about the way in which American society forces too many people to the metaphorical margins, turning them either towards active dissent or into the arms of those who offer to represent or guide them.

After all, when individuals like Stephen Paddock can pour thousands of rounds of ammunition into a crowd in Las Vegas – and when a divisive, egotistical businessman can decry politics yet still win the keys to the White House – it appears that a diagnosis for America’s condition is still required.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks