After Chilcot, Iraq will always be the ruin of Tony Blair's reputation – and unfairly so

The famous 'I will be with you, whatever' line turns out to be followed by a 'But…'

As we approach the final verdict of history, there can be no doubt now that it will be negative. Tony Blair had a good record as Prime Minister domestically, and he did the right thing in Sierra Leone and Kosovo, but he will be remembered for Iraq.

Almost no new information about the decision to join the US invasion has been available since Blair was Prime Minister, and there seems to be surprisingly little new in the Chilcot report today. Yet the opinions expressed about the same information have become progressively more hostile.

The main new information that I have seen has been the actual text of some of Blair’s notes to George W Bush. They seem to me to reflect well on Blair. He asked the right questions, even if he patently failed to receive the right answers. The famous “I will be with you, whatever” line turns out to be followed by a “But...”

The line has been known about since John Kampfner’s book published in October 2003 (he reported it as “I’ll be with you, come what may”), but the qualification, the fact that it was a diplomatic device to get Bush’s attention for an argument to build a wider global coalition, was less well understood.

Another note mentions almost in passing Blair’s fear that, if there was an invasion, Saddam Hussein might “let off WMD [weapons of mass destruction]”, confirming that his fear of them was genuine.

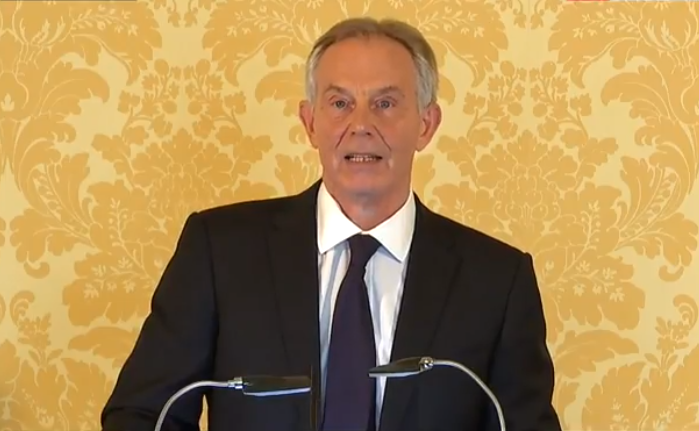

No doubt there will be other new things in the rest of the report and the hundreds of documents published with it. But so far, the argument has been spinning like a wheel that has been stuck in the mud for 13 years. Sir John Chilcot rehearsed a familiar case against the Iraq war, heavily influenced by hindsight even as he denied it, followed by Blair himself, initially tearful and contrite, repeating at inordinate length the fluent and articulate case for the defence.

Blair was as right as he ever was – read that as you may – but the magic has gone. The people who voted for him in such large numbers have moved on. His attractions of cogency and communication have become repellents. And there is a new generation for whom he is a semi-legendary personage, the warmonger of yesteryear.

He was right to disagree with Sir John – “with respect” – that Iraq was not a war of last resort. It was a binary choice, he said. He had to decide whether it was right to try to remove Saddam Hussein, and he had to decide then, in March 2003. The option of more time was not available. For once, he was brutally honest about Britain’s subsidiary role in an American decision. The Americans were going in. His only decision was whether or not to go with them. It was not a “last resort” decision; it was a “better or worse” decision.

And I think he was right to disagree about the way the decision was taken. Chilcot wanted more Cabinet discussion and more Cabinet subcommittees. Blair even said: “I accept that I could and should have presented a formal options paper [to Cabinet].” But it wouldn’t have made any difference. The Cabinet with the sole exception of Robin Cook supported the decision. Even Clare Short supported the decision.

As David Cameron said in his statement, he did everything the ex-mandarins wanted when deciding what to do about Libya. A National Security Council. More meetings, more minutes. And the consequences of intervention there were still bad, although, just like Blair and Iraq, Cameron thinks the air campaign against Muammar Gaddafi was justified.

As one of Cameron’s advisers told me after watching Blair’s news conference: “You have to take tough decisions with imperfect knowledge.”

One of the least important effects of the Chilcot report is that it has strengthened Jeremy Corbyn in his attempt to cling on to the Labour leadership. This was bound to be the case, simply by stirring up the sulphur-pit of Blair-hatred, which is one of the engines of the Corbyn insurgency in Labour. But the report is worse for the Blairites than I had expected. Corbyn had the basic political instinct to avoid mentioning Blair by name in his response in the House of Commons, and to style his criticisms in the passive. The invasion was an “act of military aggression launched on a false pretext”, which avoided the question of whether it was deliberate. The House “was misled”, he said, again avoiding the outright accusation of deception.

By being relatively reasonable (the “colonial-style occupation” of Iraq was one of few rhetorical excesses), he made a stronger case. The timing could not be worse for Angela Eagle, one of the many MPs who voted for military action in 2003, as she seeks the votes of the Labour Party members who supported Corbyn in such numbers only 10 months ago. Labour’s hope of recovering from Corbyn’s leadership has been postponed.

But the moment will pass. Iraq will always be the ruin of Blair’s reputation, but it may not yet be the end of the Labour Party.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks