A university which is a hotbed of offence-taking isn’t a university but an ideological prison camp and indoctrination centre

The freedom to think freely is more important than the right of women to enjoy equal respect to men

So how did you spend the extra time last week – that leap second inserted into our clocks to keep them in sync with the fickle Earth’s rotation? I spent my second wondering how many more it would take to slow down the ageing process. How many leaps before the Earth juddered on its axis and time reversed, as it did for Superman, and I would be able to recall the names of friends again, get out of a chair without groaning, read the number of a bus in time to hail it before it drove past me? How many before the lines of sad experience vanished from my face and the hairs retracted into my nostrils? Which brings me neatly to my theme: nostril hair.

There are two ways we can speak about nostril hair, allowing that some people might not want to speak about it at all. We can speak literally and we can speak figuratively. Allow me to speak literally first.

For my own poor part I go to great lengths to keep my nostrils sightly. I own a mirror for looking upwards, several pairs of scissors with differently curved and blunted points, and a battery-operated razor (the batteries are optional: vanity alone can power it) the shape of a small spaceship. We shouldn’t be too hard on vanity. It can be a mark of respect for the world. The day I don’t attend to my nostrils is the day I will have forsworn that world and become a different person. Someone otherwise preoccupied. Someone who couldn’t care less what anyone thinks of his appearance, someone for whom the material life has lost its appeal. I will have retreated into myself, to that place where eccentricity and maybe even madness reside. Science, perhaps.

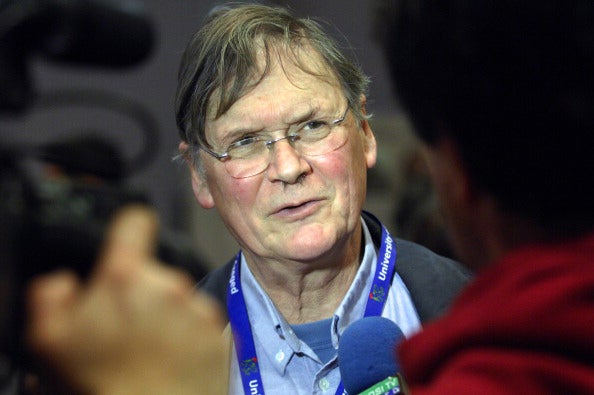

The astute reader will by now have worked out that in truth nostril hair is only my sub-theme, and that my real subject is Tim Hunt, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who recently made a joking reference to the lachrymosity (were there such a word) of women, in punishment for which University College London expeditiously removed him from the honorary post he held there.

If I say that Tim Hunt is to be numbered among those who don’t fanatically barber their nostrils twice a day, I intend no disrespect. I am now addressing nostril hair culturally. Tim Hunt has the air of a man who doesn’t put his appearance first, a man who, whether calculatedly or otherwise, inhabits that sphere of extraterrestrial idiosyncrasy whose uniform is a cream linen jacket bought from one of those shops in Piccadilly where they come pre-battered, a fisherman’s smock (probably picked up in Cornwall), stained owlish spectacles, a cord that goes around the neck to hang them from (else they’d fall into a laboratory bath) and, yes, figurative tufts of nostril hair.

Among the reasons universities exist is that such men should have a habitat. They are a dying species. When I went to university, there was almost no other way for a don to look. A few military men and dandies were the exception, but even their moustaches and cravats were mildewed and wouldn’t have passed muster anywhere but in the Fens. Otherwise, the Scarecrow look from The Wizard of Oz prevailed. Bicycle clips, one trouser leg still in the sock, ties unevenly knotted, hair growing out of their ears and from their noses, sometimes in odd fringes above their shirt collars, occasionally in tussocks on their cheeks.

This was the higher carelessness of the academic life. To have turned up to give a lecture any less neglected would have been to put show before sagacity. Nostril hair wasn’t simply an inadvertent consequence of collegiate life; it was the very badge of it.

That they held opinions abominable to those of us who tirelessly invigilate the political niceties goes without saying. Here were odd men and women, but mainly men, to all intents still living the monastic life of the 13th century. Some were even tonsured like monks and taught in tiny cells where, when they thought no one was listening, they played upon medieval instruments. To them the mundane demands of modernity were a torture.

So what right did we have to expect modern attitudes from them? Of course they were sexists, racists, pederasts, colonialists, anti-Semites. Of course they made jokes which not another living soul found funny. Bigotry was expected and even required of them. There have to be places where people let nostril hair run wild, think differently from the rest of us, implicitly call into question and even deride everything we have made up our minds about, find wisdom through unconventionality, and say a lot of foolish things along the way. Universities are such places. Correction: universities should be such places.

Show me a university which is a hotbed of thin-skinned offence-taking, where every unacceptable idea is policed and every person who happens to hold one is hounded out of a job, and I will show you a university that isn’t a university but an ideological prison camp and indoctrination centre.

Reaffirming the college’s pusillanimous decision to show Tim Hunt the door, the Provost of University College London said: “Our commitment to gender equality and our support for women in science was and is the ultimate concern.” Wrong, Mr Provost. The right of women to enjoy equal opportunities, receive equal pay and enjoy equal respect to men in science, or anywhere else come to that, is without doubt a matter of high importance. But it is not as high, if we are to talk of “ultimate concerns”, as the freedom to think freely and independently – a freedom which matters as much to women as to men, and without which equality must lose its savour.

Who wants to be equal in an institution which is frightened of the very differences it exists to foster? What shall it profit a man or a woman, if they shall gain the whole world and lose their own soul?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks