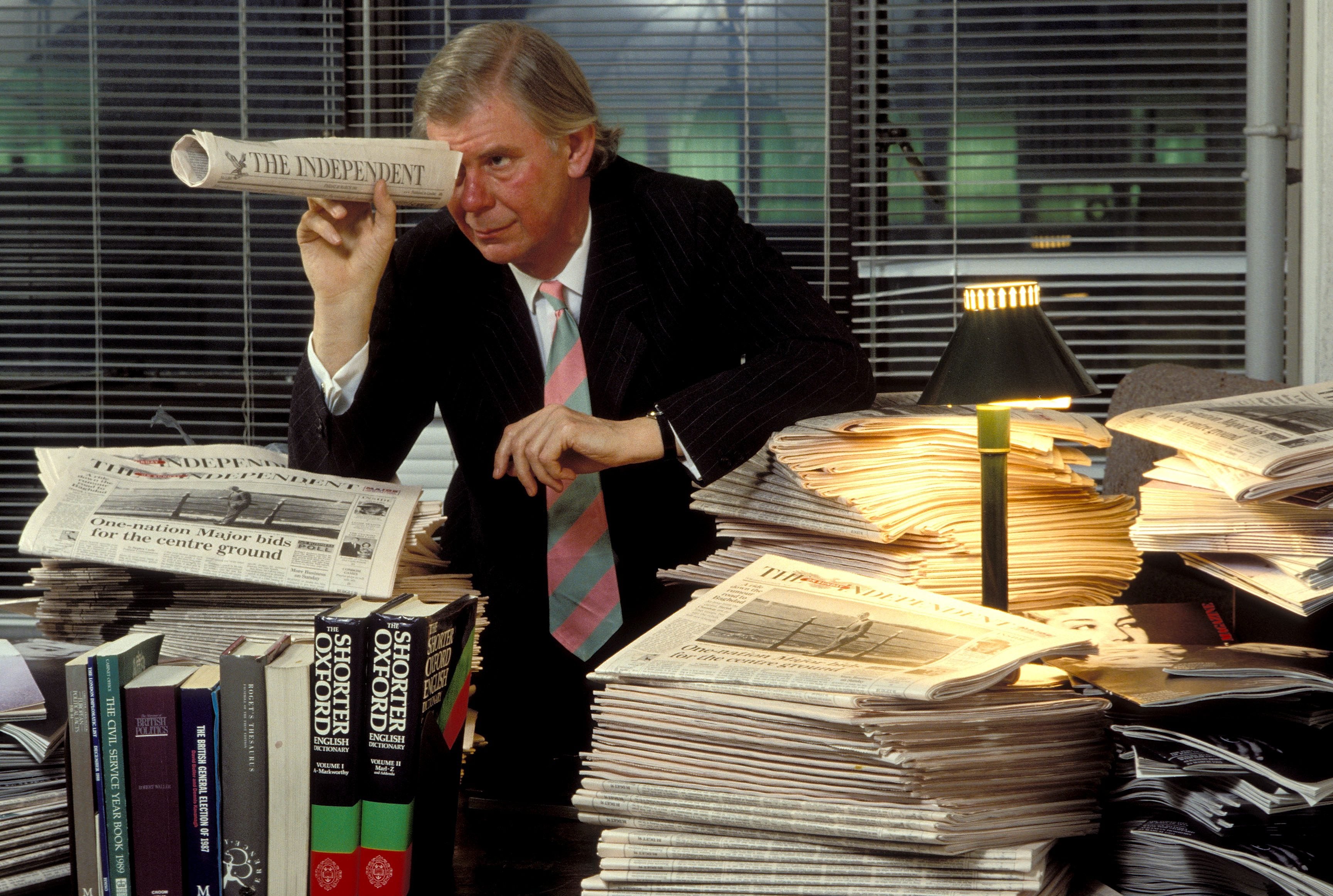

‘For Andreas Whittam Smith, anything that threatened independence for monetary gain was strictly off-limits’

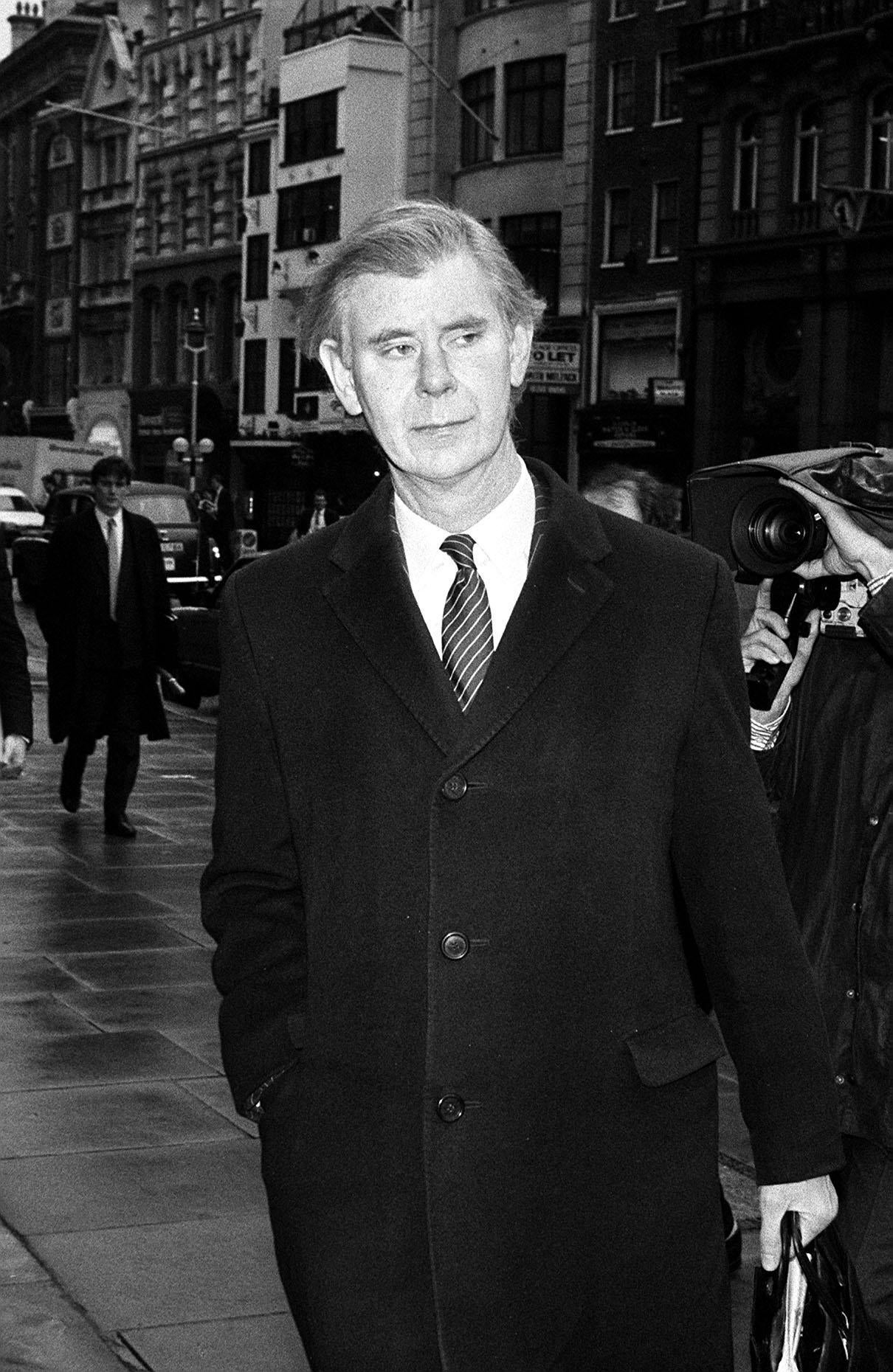

Dubbed ‘Saint Andreas’ by Private Eye, Andreas Whittam Smith might have had the image of a principled university don, but he could be ruthless and calculating when he wanted – and needed – to be too, says Chris Blackhurst

Andreas Whittam Smith could not have been a short man. If he’d been of low stature, he would not have retained the same other-worldly bearing.

Tall and stooped, he was softly spoken, often hesitant and slow in delivery. This gave him an intellectual, somewhat patrician air. He came across as a don at university, rather than a cut-and-thrust, in-your-face, newspaper editor or proprietor. Pugnacious and swaggering, he was not.

But he was brilliant, inspiring huge loyalty and admiration among the staff. Courageous, too, prepared with his fellow ex-Telegraph co-founders, Stephen Glover, these days the Daily Mail’s longtime common-sense columnist and Matthew Symonds, father of Carrie Johnson, to plunge into the shark-infested waters of Fleet Street proprietorship.

He was a man of determined principle, which somewhat unfairly earned him the sobriquet of “Saint Andreas” from Private Eye. But Andreas could be just as ruthless and calculating when he wanted to be. He wished to buy The Observer but only with the sole purpose of closing it down, to merge the historic Sunday paper with the Monday to Saturday Independent. He had the champagne ready in his office fridge. When, at the last minute, Tiny Rowland sold it to The Guardian, Andreas was furious.

His manner in meetings was deceptive – he would say little, let others speak, then give his verdict. At a morning editorial news conference, the discussion centred on House, the 1993 sculpture by Rachel Whiteread, where she’d made a concrete cast of the interior of a Victorian house. The stark structure had won her the Turner Prize.

Andreas did not want to be seen so nakedly on trend – it was not his style. He exhorted the staff to go and see it for themselves. The following day he went round the table, asking people what they thought. They gushed about how amazing and inspirational it was. Andreas listened. A news executive, new to the paper, piped up and said he found it “vapid and empty”. Andreas fixed him with a stern gaze and said, “that is not an opinion you’re allowed to have on this newspaper”. The Indy was a collective – but with Andreas firmly in charge.

His view was that his paper was to be positioned above the rest, in tone and quality. His original intention was to create a more cerebral version of the Daily Telegraph, in words and visually with superb black and white photography, believing a gap was opening up among the broadsheets as he thought Rupert Murdoch was taking The Times downmarket.

That is where The Independent went. Guided by Andreas, it was setting new standards, famed for its reporting, imagery and layouts. For many years, it was the newspaper that others across the industry aspired to work on – a beacon for independence and objectivity. Many of us took a salary cut to join; we were that keen on what Andreas was trying to do.

He had a City background, himself, yet he could seem uncommercial or rather, he had such a fixed idea of where his creation belonged that little would persuade him to change. Sales and revenue were something of an afterthought, at least that is how it appeared to us on the editorial floor. Andreas made sure we were ring-fenced, able to go about our calling, safely protected from commercial pressures.

Any suggestion of a shift downwards, threatening to sacrifice independence for simple monetary gain, was off limits. A friend in marketing rang me to say he could make an offer exclusive to Indy readers – his client was the Savoy Group of hotels and they could have a three-night stay for the price of two. That seemed like a good deal – other papers had similar reader promotions. I went to see Andreas. When I told him, he shook his head. Such tie-ups weren’t for his Independent.

One day, without warning, all the Indy staff were asked to gather in the newsroom at City Road. Andreas said he had two announcements to make: the first was that Murdoch was cutting the price of The Times; the second was that the Indy was going up in price. There was a pause while everyone took this in – there was shock and bafflement. Wait, they are reducing while we are increasing? It seemed bizarre. Andreas assured us that research showed quality broadsheet readers would happily pay more. We lost a third of our sales almost overnight.

He was famously not easily influenced. I was an investigative reporter in the City and at Westminster. Company titans and Cabinet ministers who could get somewhere with other papers’ owners and editors would moan like mad that Andreas would not take their calls, and if he did, nothing would come of them. He had excellent high-level contacts and he often knew things that we reporters did not.

Once, after I’d been working on an unfolding story, uncovering a political scandal, we were standing in a crowded lift. He nodded at me and said, with his eyes twinkling, “You’re on the right lines.” The door opened and he walked off. Another editor would have got back to their desk and carried on, furnishing what they knew. He never did. That was not Andreas’s style. He’d encouraged me and that was enough.

He also could not abide bullying, no matter how famous or heavyweight or rich the bully. He stood by his paper and its journalism, come what may. We thought enormously of him for it. Mohamed Al-Fayed complained about a piece I’d written and wrote to every Indy director saying he was especially disappointed because I’d left him “bearing gifts”. The letter came straight to me, with Andreas’s familiar handwriting at the top: “Come and see me, now.”

Knowing his stance on employees accepting freebies, I feared the worst. I said it wasn’t a Harrods platinum card or anything like that, but a Harrods teddy bear [we’d recently had a baby] and a coffee table book about the restoration of the Ritz in Paris that Fayed also owned. Andreas told me to send back the book, keep the bear (by then it was in our child’s cot). I did, then another Fayed missive landed, again to all the directors, “This was not all the gifts,” said Fayed in typical sinister fashion, as if I was playing fast and loose, being selective in what I kept and chose to return. Andreas wrote back simply: “This stops now.”

Later, I was deputy editor and editor. Andreas was by then a non-executive director but still held great sway as a spiritual figurehead, a constant, enthusiastic keeper of the Indy flame. He was someone to turn to in a crisis. He was always unflappable, calm, measured, and, where editorial was concerned, wise. He could be counted upon to be supportive, taking the side of the journalists against any proposal that he regarded as possibly commercially exploitative and damaging to that Independent ideal.

For a period, we sat on the company board together. He and I were charged with trying to find an outside investor to pump in extra cash. We arranged to meet a Middle Eastern billionaire who had expressed an interest in coming in. He’d made a fortune wheeling and dealing, some of it in dubious circumstances. In another guise, he might have been just the sort for Andreas’s Independent to investigate.

Over coffee at The Landmark hotel in London, we outlined how the Indy was a great investment, how readers loved our content. Towards the end, Andreas suddenly said: “You know, it’s one of my proudest claims that on no day in its history has the paper made a penny in profit, but we’re still here.” The Kuwaiti was bemused.

Afterwards, in the cab, I said: “Do you know when we lost that, Andreas? When you said we’ve never made a profit.” He said, “Do you think so?”, and gazed out of the window.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks