If Anthony Burgess doesn’t merit a blue plaque, then few do

He had a phenomenal knowledge of languages, philosophy, religions and more, on top of his writing

The London Blue Plaque Scheme has been around for a long time – the first-ever plaque in 1867, attached to a wall in Holles Street, off Cavendish Square, celebrated the one-time residence of Lord Byron – and has proved a nicely understated way of celebrating the creative dead.

Statues can be used to commemorate statesmen, politicians and soldiers because their lives usually involved declaiming or giving orders to thousands of people, but they seldom seem appropriate for writers; only Shakespeare has the stature (and career theatricality) to justify one. For men and women who invented immortal stuff while seated indoors at their desks, drawing boards, easels or musical staves, the blue plaque seems just right. It combines the domestic and the apocalyptic. Right here, it says, behind these modest, suburban walls, Mr or Ms So-and-So conjured a masterpiece from their imaginations, in between doing ordinary things like making tea, reading the paper and worming the cat.

Six houses down the road from me, a plaque reveals that Thomas Hardy lived there between 1863 and 1874, the years when he was a student at the University of London and then an architect. There I was, thinking he spent his whole life in Dorchester, when for years he lived practically next door to Royal Oak Tube station, and probably availed himself every Saturday, to his neighbours’ relief, of the facilities at nearby Porchester Baths.

In Doughty Street, you can see the house where Dickens wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby. In Primrose Hill you can find the dwelling where Sylvia Plath wrote the Ariel poems, and, in St James’s, the house where Sir Isaac Newton performed his alarming experiments with optics by poking bodkins around his eyes.

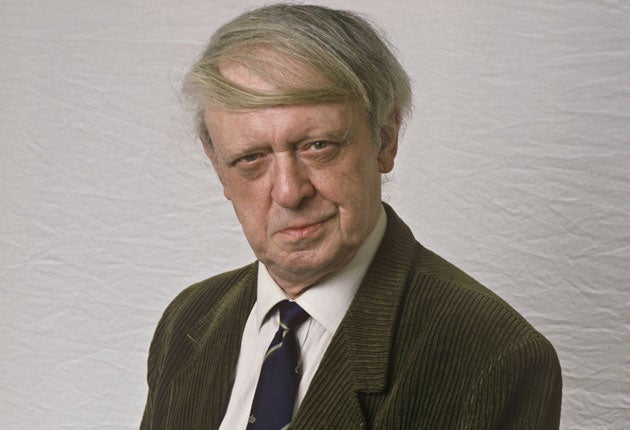

Who, though, decides which writers, musicians, painters, scientists, historians and so forth deserve one of these £1,000-a-time plates? The question is prompted by the leaking of the Blue Plaque panel’s deliberations about Anthony Burgess, the Manchester-born polymath, novelist, critic, composer, author of A Clockwork Orange and Earthly Powers, and dizzy-makingly omniglottal manipulator of language.

He was nominated last year by the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester. The foundation wanted the blue roundel to adorn the house at 24 Glebe Street, Chiswick, west London, where he lived between 1963 and 1968, and wrote six novels, three books of criticism and umpteen translations. They thought it would be a shoo-in because Burgess fulfilled most of the criteria: he was famous (his work was filmed and on the school syllabus); he was “considered eminent by a majority of members of his profession”, give or take the bitchiness of the literary world; he’d “made an outstanding contribution to human welfare or happiness”, at least among readers and TV chat-show watchers; and he had been conveniently dead for over 20 years (he died in 1993).

The advisory panel, however, weren’t impressed. “The panel agreed,” read the minutes, “that Anthony Burgess was a prolific and energetic writer, but that it was too soon after his death to evaluate the merits of shortlisting.” English Heritage explained that the panel “felt his overall significance and profile were not yet strong enough to make a case for a blue plaque”.

I’m not sure who sits on the panel these days (recent cuts have played havoc with the scheme, and several members resigned last year) but many things about these boneheaded remarks cause alarm. The panel “agree” that Burgess was “prolific and energetic,” meaning he wrote lots of books using lots of fancy words – not a very literary judgement is it? They think it’s “too soon” to decide his worth, having already set a minimum of 20 years for posterity to get its evaluative act together. Are they waiting for 30 years to elapse, or 50 or 100? Are they hanging on to see if his works stay in print? Or for some super-critic at some future literary festival to opine that yes, Burgess was indeed a Major Writer? Will that decide for them? As for suggesting that his “overall significance and profile” weren’t yet strong enough for plaque-dom, words fail me. Will the panel celebrate only creative types who’ve become a brand rather than published excellent work over many years?

The odd thing is, of course, that Anthony Burgess was something more than “just” a writer. He was a polymath, a magisterial, panatella-waving know-all, a Renaissance man with a phenomenal knowledge of languages, philosophy, religions, culture, music, art and food. His conversation could switch in a moment from the Albigensian Heresy to the Jerusalem artichoke, from Russian loan words to Rameses II’s invention of hieroglyphics. He had a talent for reducing complex subjects to clear and manageable proportions. And his headlong creativity was of an exuberant, boisterous quality that’s rarely seen in English literary circles – the spirit of Fielding, Dr Johnson, Thackeray and Dickens.

I’ve long been a fan, so I’m biased about his suitability for en-plaque-ment, both for his literary brilliance and for what he represents as an embracer of the whole world of knowledge. I’d like to think that seeing his plaque on a modest house in Chiswick might inspire future pedestrians to Google his name and discover what a titanic figure he was. Isn’t that rather the point of blue plaques? Not just to mark the one-time living quarters of the super-famous (like Handel and Jimi Hendrix whose plaques adorn adjacent properties in Brook Street, Mayfair) but to call attention to vivid, bustling, contrarian figures on the British cultural scene, whose torrential imaginations left the arts-consuming public stunned, whose example inspired the nervous and shy to utterance, and whose modest home in a London street became a crucible of achievement?

Twitter: @JohnHenryWalsh

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks