Innocent until proven guilty? Not under the EU’s justice system

Corpus juris, used in Europe, is not a system of justice we should be welcoming

We all know that early November is “Remembrancetide”. Taking pride in our armed forces –something I wholeheartedly think we should do – is trendy and sophisticated these days. Everyone from the Duchess of Cambridge to schoolgirls donating their pocket money supports “our boys and girls”.

It’s also inevitable at this time that stories appear about celebrities, or “Channel 4 newsreaders and left-wing comics”, as I like to call them, not wearing their poppy. Despite calls for us to be outraged, the Royal British Legion will always respond in the same way: by pointing out that millions died for our freedom, which includes, if one wishes, the right not to wear a poppy. In short, they died for our liberty.

Freedom, liberty and justice are something I think the left of politics and the media have completely wrong. In a flurry of “isms” they have closed in on free speech, on the right of protest and demonstration, and clamped down on opposition to certain views. But nowhere do I think they have it more wrong than the creeping harmonisation of EU justice and home affairs.

Viviane Reding, the EU’s Commissioner for Justice, says it would be “crazy” for the UK to opt out of these transfers of powers to Brussels. “Do you want criminals and paedophiles running freely around on the streets? Is that really in the United Kingdom’s best interest?” she asked. Is Brussels going to release some criminals if we don’t sign up, after it’s forced Westminster to give them the vote?

Such intimidatory language is typical of Eurocrats. Reding speaks as if the UK has no police force or justice system, when in fact our traditions of habeas corpus should be held up as a beacon of fairness.

Unlike most continental countries, Britain has had a continuous and peaceful constitutional development going back hundreds of years. The last significant armed conflict in mainland Britain was the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. Disputes have been settled and power has passed from one government to another essentially by voting (with an ever-increasing franchise) since the end of the Civil War. The losers have accepted the verdict of the voters without resorting to protest and rebellion. This history may lead some commentators to overlook the central role of physical force in the maintenance of state power.

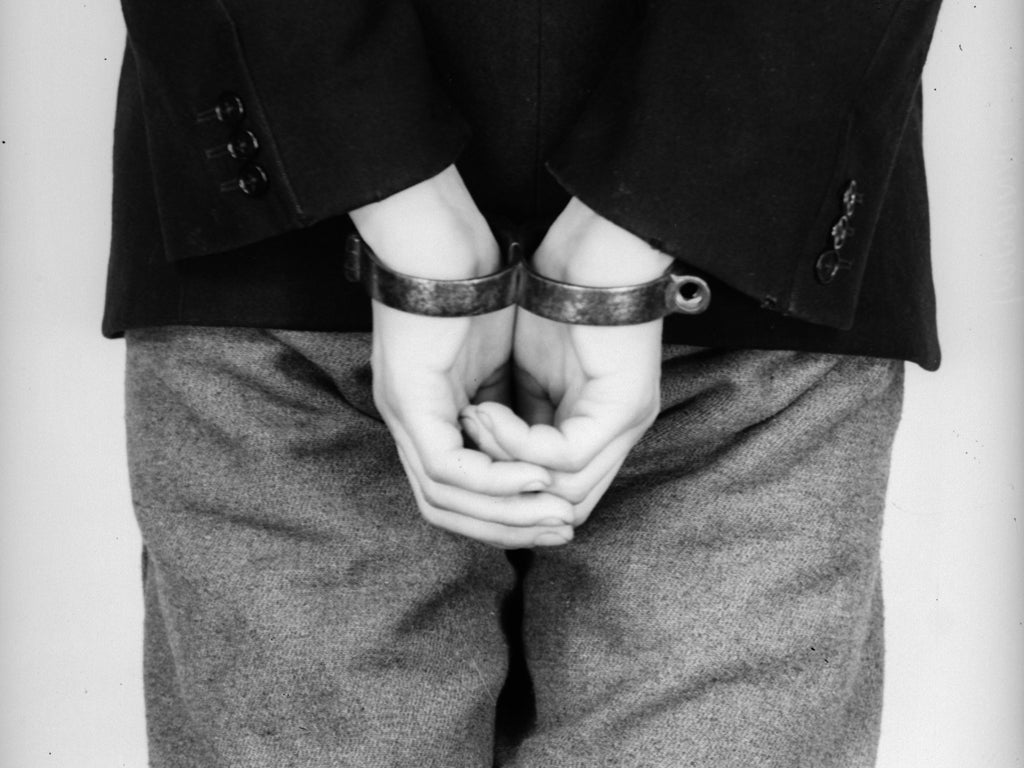

Corpus juris, used by our continental neighbours, is not a system of justice we should be welcoming in the UK. It is alien to our beliefs of “innocent before proven guilty” and of limiting the power of the state. Once the power of law enforcement has been handed to another institution, there is no guarantee we can get it back. Certainly the endless rhetoric of “repatriating powers” to Westminster politicians, scared of the increasing hostility to the EU project and the rise of Ukip, has seen no reversal in the flow of powers.

The EU court already exists: the plans under the Lisbon Treaty are to extend its jurisdiction. I question whether many MPs know the details of these measures.

As far as I am aware, there is no official research centre of comparative criminal procedure in any university in Britain, nor has any previous government undertaken any detailed research into the workings of the criminal law system of our EU partners. And yet we have been signed up to a series of treaties that bring ever-closer union.

In England in 1215, King John was prevailed upon by his barons to give his assent to the Magna Carta. This established certain limits on the power of the king to ensure he wielded his authority for the purposes of justice, not vindictiveness.

What we may not appreciate in this country is that at the same time, the opposite was happening in Europe. For example, the Holy Inquisition was being set up in Rome. This system of combining the prosecutor and judge is something which formed the basis of the legal system in Europe. They are no longer the same person, but are instead salaried civil servants working cheek by jowl.

My question to those who support this transfer of powers to the EU is simple: “Do you believe in the principle of innocent until proven guilty?” Perhaps they should speak to Andrew Symeou, who was extradited to Greece and languished in jail there based on the signature of a magistrate that no UK judge could overturn despite the evidence against him being obtained under duress. He was in a Greek prison for almost a year and denied bail until the trial was adjourned.

If we do not opt out of these Justice and Home Affairs measures, we risk our system being replaced by a system as in Italy, where criminal investigations make no distinction between imprisonment for prosecution purposes or investigative purposes. Amanda Knox is a high-profile example of this system. She was subject to her personal life being publicised and attacked in a way which would not have been permitted here or in her own country of the US. Indeed, the police said she had committed slander by trying to defend herself. She was told she had HIV so that she would reveal details of her ex-partners – details which were then released to the media.

The debate a few years ago on 90 days’ detention without charge, which was subsequently defeated, pales into insignificance compared to what British citizens could be locked up for, for months on end, if the EU gets its way. It is essential that we have a public debate on this so we do not end up with this system by default.

Nigel Farage is the leader of Ukip

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks