Iraq crisis analysis: Our leaders have no appetite for further conflict

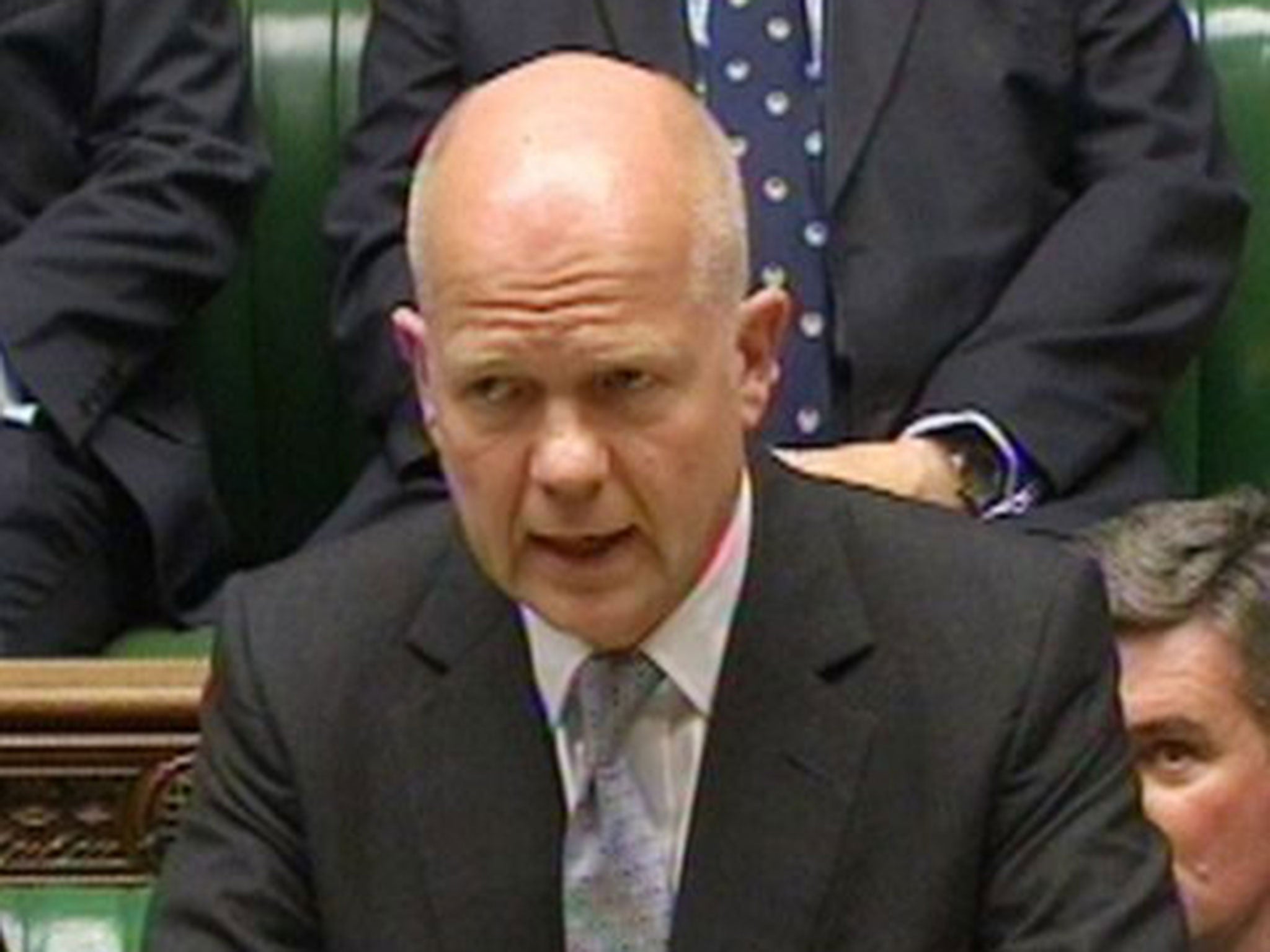

The Foreign Secretary, William Hague, noted the White House was contemplating the use of drones, but made clear Britain would not follow suit

Eleven years after Britain backed the American-led invasion of Iraq, the spectre of Tony Blair continues to haunt British politics.

In the House of Commons yesterday, senior figures from all parties were united in opposition to military action to stop the march of Isis militants across northern Iraq.

Nor was there much enthusiasm for the former Prime Minister’s call for the West’s leaders to consider launching targeted air strikes.

The Foreign Secretary, William Hague, noted the White House was contemplating the use of drones, but made clear Britain would not follow suit.

Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister, would only say Britain could offer “passive assistance” to the Americans, a possible hint that the Government could allow strikes from airbases in the UK.

The near-universal reluctance to authorise the use of British firepower comes almost 10 months after the Commons rejected David Cameron’s plea for limited air strikes in Syria to reverse the advance of President Bashar al-Assad’s troops.

That dramatic vote, which also stymied any chance of Barack Obama launching action in Syria, has made a profound change to British foreign policy.

It is difficult for the foreseeable future to imagine the Commons authorising military action in a state thousands of miles away, apart from the limited “counter-terrorism support” supplied to the Iraqi forces and support for British embassy staff.

The lack of any appetite for becoming embroiled again in Iraq was underlined by the failure of any MP to raise the subject last week at Prime Minister’s Questions.

“We are not planning a military intervention by the UK in this situation,” Mr Hague said yesterday. Asked whether Britain could join air strikes, he replied that he “could not be clearer” that would not happen. He added: “The US is much more likely to have the assets and capabilities for any outside intervention.”

British political leaders are left with no alternative but to try to find other solutions to the civil war engulfing Iraq and the deepening instability across one of the world’s most volatile regions. That means performing a remarkable diplomatic volte-face and reaching out to the Iranian government, long shunned by the West.

But on the basis that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, encouraging Tehran’s intervention could be the key to combating the Isis threat.

Iran is considering sending military help to the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, a move that would stiffen the resolve of Iraqi forces. There is a danger, however, that the move could only inflame the Sunni fighters marching under the Isis banner.

If they can be turned back, Britain will put pressure on Nouri al-Maliki’s administration to abandon its sectarian approach and work for a pluralistic government involving Shias and Kurds.

In the even longer term, the Government will harbour hopes of the region’s most powerful states, including Saudi Arabia, coming together to try to resolve the centuries-old Sunni-Shia faultline.

British politicians risk falling into the trap of reviving old arguments about the 2003 Iraq war and the lack of planning.

Mr Blair’s comments at the weekend, insisting the invasion is not linked to Iraq’s insurgency added fuel to that, particularly as the Chilcot inquiry into the war is expected to report within six months.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks