It's not "left-wing campaigners" who are defending judicial review. It's anyone who cares about justice

Arbitrary government decisions have been highlighted by both the left and right

Following a sustained campaign from the Legal profession, last week the Government ditched plans to introduce price-competitive tendering for criminal legal aid contracts. But this is no cause for celebration. Instead, the Government proposes further punitive reforms, which will damage access to justice for all; among them is a proposal to significantly reduce the number of judicial reviews.

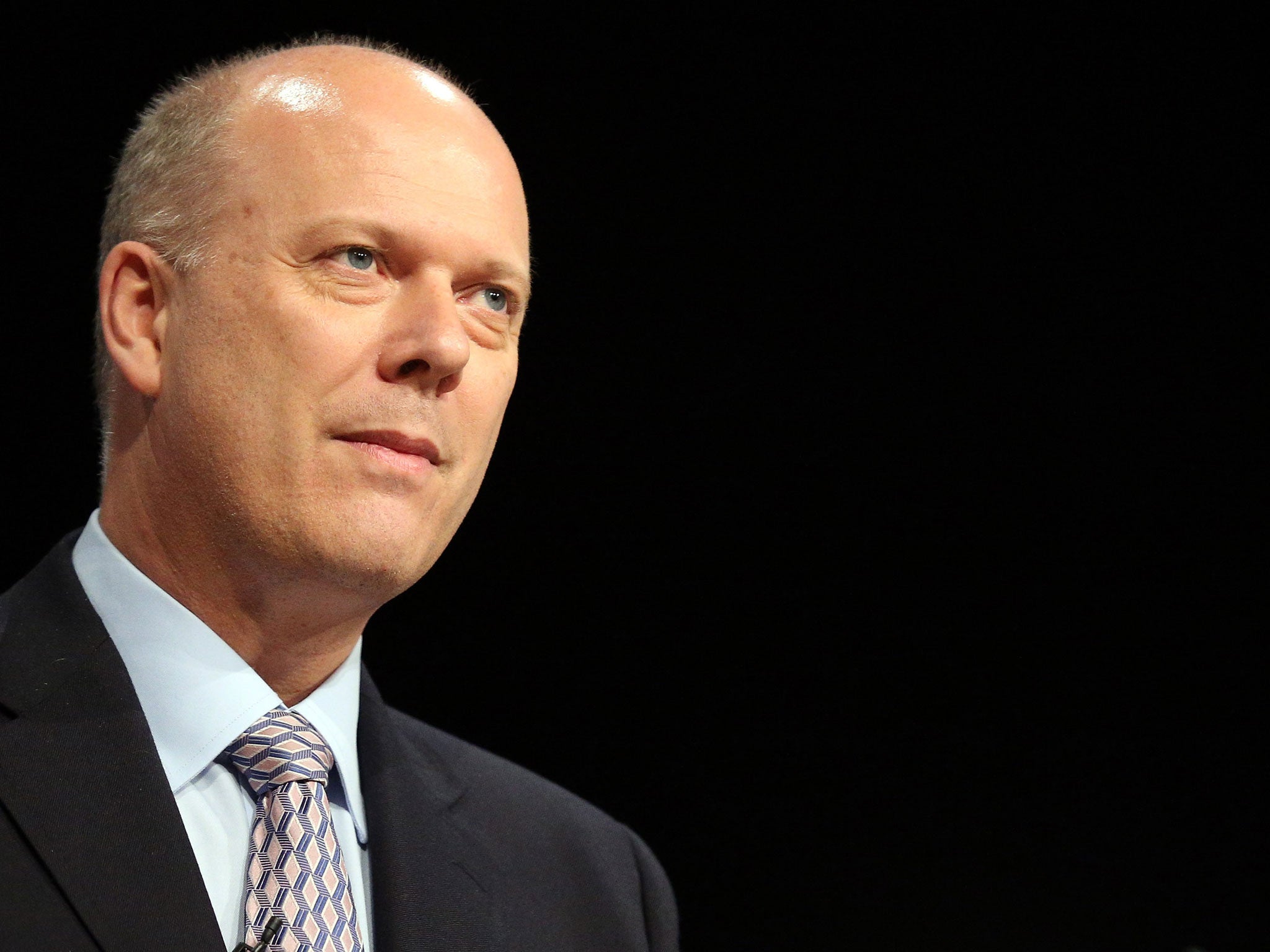

Currently, courts judicially review decisions of the Government and public bodies to ensure they are lawful and do not breach our civil liberties. Writing for the Daily Mail this week, Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, opines judicial review is a promotional tool for left-wing campaigners. Actually, judicial review is not about left or right. People of all political persuasions use judicial review, including the Countryside Alliance over fox hunting and the Daily Mail over the Leveson Inquiry. By framing the debate in an over-simplistic narrative of left vs right, Grayling is trying to distract us from the real purpose of judicial review: it is about ensuring public bodies and the Government are subject to, rather than, above the law.

To make the case for retaining judicial review it is important to review its historical trajectory. It did not evolve during a left-wing campaign, as Grayling might like to suggest. Rather, it gained ground in the mid 1970s in response to appalling abuse in the British criminal process and prisons following allegations of injustice regarding suspected IRA terrorists. It soon became apparent that miscarriages of justice frequently occurred in criminal trials and those wronged by the state needed a means to challenge this injustice.

Exposure of arbitrary and unlawful government decision-making was highlighted by charitable organisations on the left and right, including the Catholic Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland, the Women’s Movement and campaigns against racial discrimination. Mobilising in opposition to unfair government practice, they sought to pursue the expansion of human rights through the courts and to challenge the power of the state. The judiciary was responsive and showed a willingness to hold the government to account for unfair decision-making.

This increasing judicial activism and third sector movement in the UK from the mid-1970s to the late 1990s was part of a wider move towards the development of international human rights standards and integration into the European community. The UK Parliament in 1998 incorporated the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) into British law through the Human Rights Act 1998. British judges now judicially review decisions by public bodies and the government to assess compliance with the ECHR.

Only last month a successful application for judicial review was brought by the family of Olaseni Lewis against the state after Lewis, aged 23, collapsed following prolonged restraint by 11 police officers in custody. He later died. The High Court ruled the investigation into the death of Lewis by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) was unlawful and breached the ECHR. During the investigation police officers responsible for the death were not cautioned nor were they questioned in interviews, so their accounts of the events remained untested. Unsurprisingly, the investigation concluded Lewis’ death was not as a result of disciplinary or criminal wrongdoing by any officer.

The case of Lewis will fundamentally change the way in which investigations are conducted by the IPCC. Investigations must now involve rigorous questioning of relevant officers - under caution - to determine whether criminal proceedings should be brought against any officer. The outcome of this judicial review will hopefully prevent other families going through the same ordeal as the family of Olaseni Lewis. Sadly Lewis’ case is one example among thousands where the state has acted outside the law in breach of our civil liberties.

Should Grayling succeed in restricting judicial review, there will be no other means to challenge decisions taken by the state which breach our human rights. Once judicial review is restricted, the Human Rights Act will slowly become superfluous. Indeed, eroding the Human Rights Act supports the Home Secretary, Theresa May’s long-held aim, which is to scrap the legislation and withdraw from the ECHR.

Grayling wishes to return to a time when the state had overriding power to regulate and control citizen’s lives through unscrutinised decision-making. With no checks and balances in place, the state can sanction deplorable acts, as occurred in the case of Lewis, without any fear of review. For decades both the left and right have fought to ensure the government and public bodies comply with the law and are held accountable. Now both sides of the political spectrum must join together once again to reject this latest attack on justice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks