Losing my religion: Why I realised that I could no longer fake a tribal attachment to Judaism

Simmy Richman returns to his bar mitzvah days and traces back to when his disbelief in God began

Religious people have their Damascene moments, but atheists often have only the vaguest recollection of the point at which the scales dropped from their eyes. Me, I can trace my disbelief in God back to two distinct childhood memories. To understand those events in context, you’ll need a little bit of background.

Where to start?

Here’s the problem when you talk about anything to do with Judaism. It’s a religion, sure, but it’s mostly not that for many people who are born into it. In the main – and I’m going to try hard not to generalise here – the kind of Jews I grew up around called synagogue shul but didn’t go to it, called the sabbath “shabbas” but did not observe it and did not, strictly speaking, keep kosher. Neither did they show any of the outward signs that would allow strangers to identify them instantly as Jewish. If they want you to know they are Jewish, they will proudly tell you. They’re not hiding anything. It’s just not fundamental to their everyday lives. You’re on a need-to-know basis, and when you need to know (perhaps when they invite you to, say, a son’s bar mitzvah), they’ll tell you that, yes, they are Jewish, but no, they’re not really that observant.

I have no idea what the statistics would tell you, but from first-hand evidence gathered unscientifically from my immediate surroundings and beyond, I’m going to guess that around 75 per cent of Jewish people are not the kind of Jews who go in for the religious observance/outward signs (yarmulkes, dangly hair bits) thing. It is widely accepted and understood that the vast majority of Jews will go to synagogue maybe two or three times a year (Rosh Hashona and Yom Kippur are the biggies) and will make a show of keeping kosher at home only to dine out at their nearest McDonald’s as and when the next Mac attack strikes.

I’m not saying that we are a bunch of hypocrites, but we undoubtedly are. It’s not just that, though. We are, I prefer to think, a complex and conflicted people and for reasons too complicated and boring to go into, most Jews are of the pick-and-choose variety, selecting the laws they wish to keep and finding endless excuses to dispense with those that are too much bother. There are, precisely, 613 commandments that the observant Jew must live by and, as with so many other aspects of the religious code, it feels as if most of these are to do with food. Don’t eat this, do eat that, don’t eat this until this much time has passed since you ate that, and so on. The upshot of all this madness is that my mum did what she could to run a kosher home and my dad interpreted the texts to suit all practical purposes.

At home, meat would be bought from a kosher butcher, gelatin (a banned piggy product) would sneak in in the form of jellies and chocolate bars and sundry larder items whose labels were never checked scrupulously enough. In this way do most modern Jewish people find their lives self-governed. Can anyone live to the letter of the ancient texts and countless interpretations? A saint only. So let’s bend the law to serve our needs. Let’s reform the rules to make them more manageable. Hell, let’s break the little buggers at will when they seem – and they often do seem – entirely ridiculous and out of step with the modern world.

We lived in a world of secular Jews or, to be more precise, a north London suburb of secular Jews. It was, as suburbs of secular Jews went back in the 1970s, not too bad I suppose. There were others that were way more ostentatious. Here, everyone was middle-middle-class: a nice car or two, a second bathroom, perhaps; nothing too opulently resplendent. These were family homes to be lived in, not the showroom homes you might find in similar suburbs today.

From what I could tell growing up, north London Jews in the 1970s were perfectly comfortable socially just as long as they were mixing with other north London Jews. But while my parents’ generation tended to shy away from people when they failed to find an almost exact match, I grew up intrigued by the other, obsessed by the tiny ways in which you might tell whether other people were more bohemian, more rich or more poor than we were. Were they more religious, less religious? Other. I’m not sure that I ever tried bacon at any of my completely non-observant friends’ houses but I can remember smelling it cooking and knowing that one day I would. Because for me, Judaism always felt – as a character in an Isaac Bashevis Singer novel puts it – like a pack of cards. You build it up with every observance and good deed and prayer, and if you neglect any of these in favour of any kind of secular satisfaction, the whole thing collapses.

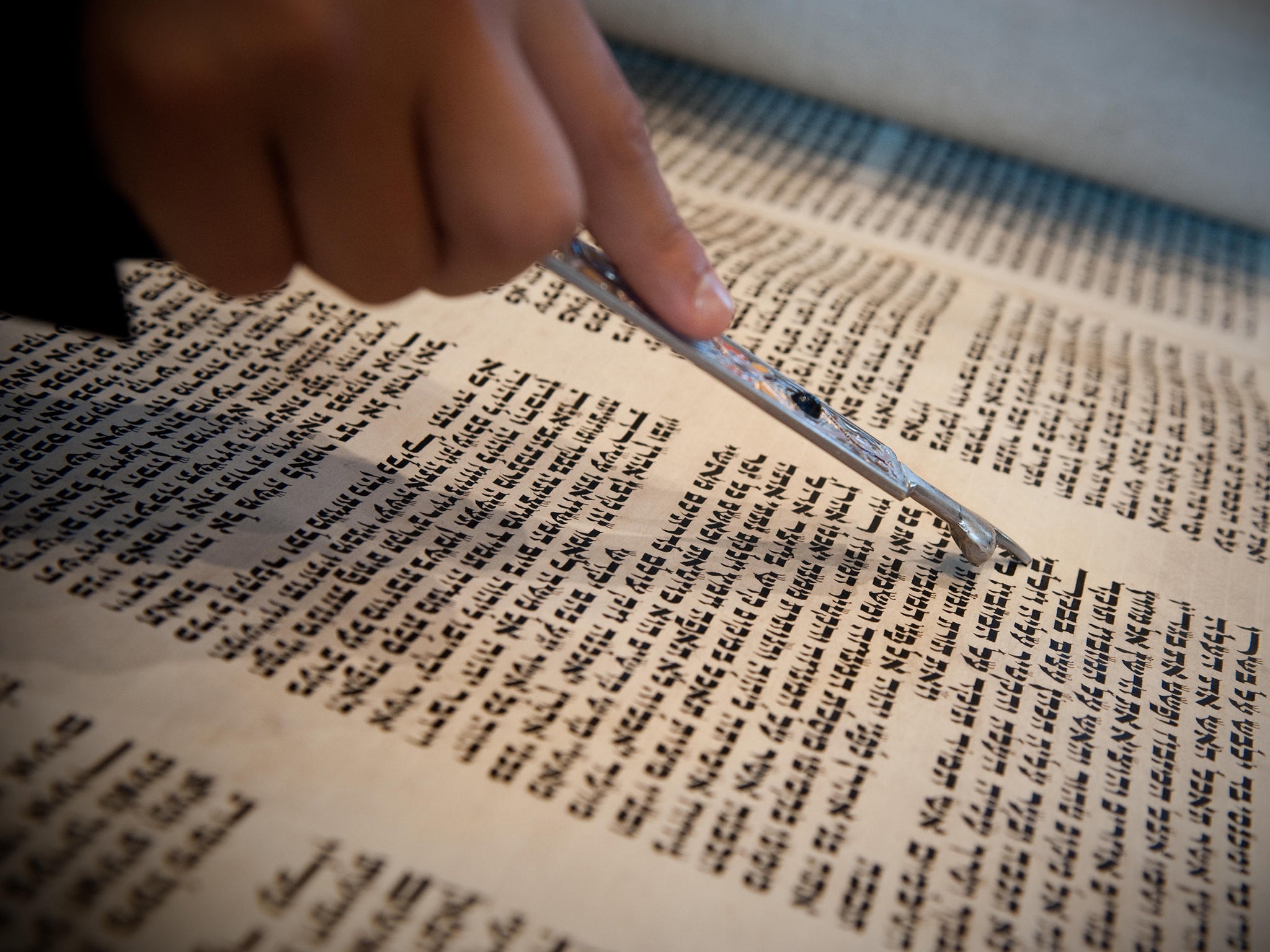

This, anyway, is how it was for me, and the first card was pulled out, Jenga-like, before I’d even reached manhood in the eyes of my people. It was 4 October 1976 and Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. The day for all those Jews who might only go to synagogue once or twice a year. The big day. The Day of Atonement. The day of no food or drink or toothpaste from sundown the night before until sunset on the day itself. My dad, a three-visits-to-synagogue-a-year man, loved Yom Kippur even if the service was interminably dull and the shul smelt of stale breath. If you met him only on this day each year, you might think you were meeting the most devout Jew in all of Jewtown. Such was his eagerness that this year he had gone on ahead to get there as prayers started and to hold the wooden seat next to him vacant for his youngest son, 12, who would be following the service alongside him but who had yet to wake up.

The reason that this year mattered was that the following summer would be my bar mitzvah and it was the done thing that, the year before you officially became a man, you would attempt the Yom Kippur fast for the first time. This was my big moment. There had, as there always had to be in this Yom Kippur matter, been a big meal the previous night to “see in” the fast so there was no way I can have woken up particularly hungry, but, well, there did happen to be this sweet shop on the walk to shul and, what do you know if – in spite of the fact that I am wearing a suit and smart shoes – I don’t stop in and absent-mindedly pick up a Mars bar.

I’m just inside the shul gates when I realise that the guy on the door, who is only there to check that all is well and safe, is looking at me strangely. And then it hits me. I am eating a Mars bar while walking through the shul doors. On Yom Kippur! Will word get out? Am I to be shunned or expelled like an errant Amish from the heart of my own community? No. The guy on the door gives me that look of condescension that only a guy guarding a shul can give you and asks me to throw the chocolate away in a dustbin across the street before he’ll let me in.

I am cursing myself under my breath for being such a fool. What was I thinking, or rather not thinking? I feel chastened, shamed, devastated.

Still, it was the best chocolate bar I ever ate. And the reason it tasted so good was that it served to confirm something I had realised about my fragile belief in God a few years earlier. I would have been around 10 years old when the following happened...

You get brought up in a house with any kind of religious background, and the very least you’re going to get out of it is some kind of moral framework. And so it was in our house: good and bad differentiated; right and wrong clear cut. Within this code there are many commandments, but few are as unambiguous as truth = good, lying = bad. Get it? Got it? Good. The lessons from home were reinforced at a nearby Jewish primary school, where I would meet as many children as much like myself as possible, and the rules were consistent and unerring. Nevertheless, though the primary school in question was attached to a secondary school, entrance was not a given and a preliminary interview would be required.

So we set off, Mum and me, a young man and his mother heading out to secure his place at the prestigious and academic Jewish learning establishment but a couple of miles from the family home. What could be easier? The interview a mere formality; the jump from one school to the next assured. Except that’s not how things turned out. Suddenly, there I was in what I remember as the headmaster’s office being asked all sorts of questions I hadn’t expected. Did my parents keep kosher at home? Check. (There seemed no need to point out the inconsistencies here. What’s a little gelatin between friends – and anyway lies of omission are permitted, right?). What synagogue did we belong to? And then, the humdinger came: did I always observe the shabbas and keep it holy?

Truth good, lying bad, remember? “Not really,” I say proudly. “We do Friday-night dinner but as far as going to shul and not travelling in a car and not watching TV is concerned… No. I have to tell you that we don’t keep shabbas, actually.” A thin smile from the guy on the other side of the desk. I return it and walk out, pretty damn pleased with my honesty.

Back in the car, Mum inevitably asks how it went. I relay all the details, including my fine upstanding answer to a question obviously designed to trip me up.

“You told them what?”

“That we didn’t really do shabbas.”

“What were you thinking?”

“Er, I was thinking that you’ve always told me that honesty is the best policy.”

Cue multiple threats of a “wait till your father hears this” nature.

Even (especially?) at 10 years old, life can be pretty confusing at times. But while the self-righteous, morally indignant part of me would swear that I was right even in the face of my father’s fury, the truth is that I probably knew exactly what I was doing: sabotage. Here I was, an average kid who could spot bullshit from a mile off, pointing out the hypocrisy he could see and sense all around him and deciding that he wanted no part of it. And if sticking to what you know to be right means that you can’t land a place at the nearest centre for Jewish indoctrination, then so be it.

Let my parents find somewhere else for me to go to school. Somewhere I might meet people from all walks of life, a variety of religions and races. And who, I decided in my own mind, wants to go to a school where it’s just nice little Jewish kids anyway? I would be a 10-year-old of the world. I would question and challenge this absurd notion that a Jewish education is the best thing for me and escape the confines of my upbringing in the process. Hell, if I played my cards right, I might even get sent to a liberal school with girls.

But I wasn’t going to be allowed to slip away that easily. Because the truth was that the secondary school that had turned me down was prepared to accept my parents’ challenge of that decision. It was an appeals process that, as far as I can understand it, involved money changing hands. Bribery, by another name – and where that particular Jewish secondary school was concerned that name was “voluntary donation”.

Great. I’m in. Woop di doo. The instinctive pre-adolescent atheist will spend the next six years at what is essentially a factory for frummers (observant Jews). Was I consulted? No. It was a fait accompli and all I could do was go along with it, although a subconscious decision had already been taken that they (my parents, the school) would never turn me into one of those pick-and-choose Jews I had grown up surrounded by.

In such ways are the seeds of dissent sown. Though I wouldn’t read the Singer book (it’s called Shadows on the Hudson and it’s a doozy) until many years later, this moment and the Mars bar incident that would follow a year or so later, were the precise points at which my religious house of cards lurched, and then collapsed in on itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks