Oprah is wrong. Atheists can experience wonder and awe

Those who believe in God do not have a monopoly over possession of that magnificent sense of the sublime

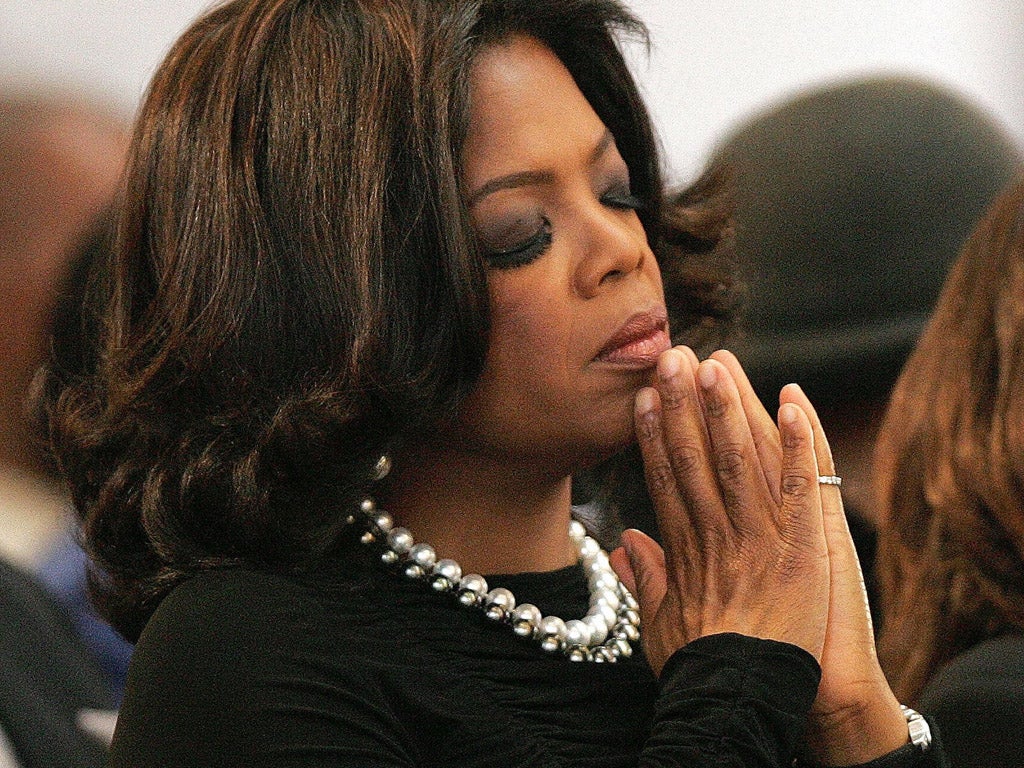

In one sense Oprah Winfrey was absolutely right when she lectured the humanist swimmer Diana Nyad about the inconsistency of the outlook of atheism with a sense of awe. For Oprah, a woman of faith, the sense of wonder and awe are inextricably intertwined with religion and God.

Indeed since the emergence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, awe is the mandatory reaction that the true believer is required to have towards God. From this perspective the sense awe and wonder is bounded and regulated through the medium of religious doctrine. In contrast, those of us who believe that it was not God but humans who are the real creators are unlikely to stand in awe of this allegedly omnipotent figure.

Although in the 21st century the term awe and awesome are used colloquially to connote amazement and admiration historically these words communicated feelings of powerlessness, fear and dread. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us, that awe means ‘immediate and active fear; terror, dread’. The OED explains that from its original reference to the Divine Being it has acquired a variety of different meanings, such as ‘dread mingled with veneration’ and ‘reverential or respectful fear’. All these meanings signal one important idea which that ‘fearing’ and ‘dreading’ are inherently positive attributes to be encouraged.

The religious affirmation of fear and dread of a higher being is indeed alien to the humanist view of the world. But does that mean that Oprah is right and that atheists cannot wonder and awe? Not at all. Those who believe in God do not have a monopoly over possession of that magnificent sense of the sublime that catches us unaware in the face of the truly mysterious. Atheists and humanist experience wonder and awe in ways that sometimes resembles but often differs from the way that the religious people respond to the unknown.

We all have the capacity and the spiritual resources to experience the mysteries of life and the unexpected events that excite our imagination through a sense of wonder. Those who stand in awe of God internalise their sense of wonder through the medium of their religious doctrine. Their response can possess powerful and intense emotions. But the way they wonder is bounded by their religious beliefs and their conception of God. In a sense this experience of spiritual sensibility is both guided and ultimately dictated by doctrine and belief. Historically those religious people who dared to go beyond these limits risked being denounced as heretical mystics.

In contrast to the way that religion does wonder, atheists and humanists possess a potential for experiencing in a way that is totally unbounded. Humanists do not stand in awe of the mysteries of God but truly wonder at the unknown. Through the resources of the human imagination (humanities) and of the sciences the thinking atheist realises that every solution creates a demand for new answers. That’s what makes our wonder so special. Instead of dreading and fearing, it empowers us to set out on the quest to discover and understand.

Experience shows that the capacity top wonder is a truly human one. Toddlers and young children do not need God to wonder at the mysterious world that surrounds them. At very early stage in their life they express their sense of astonishment and wonder without effort or a hint of embarrassment. Thankfully most of us continue to be motivated and inspired by the mysteries of life.

One final point. There are of course some new atheists who insist on living in a spiritual-free world. From their deterministic perspective everything is explained by neuro-science or our genes. But what drives them away from wonder is not their atheism but their inability to engage with uncertainty. In that respect they are surprisingly similar to those who embrace religious dogma to spare themselves the responsibility of engaging with the mysteries that confront us in everyday life.

Frank Furedi’s Authority: A Sociological History is published this week by Cambridge University Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks