Peter Hain is out of order in calling for Bloody Sunday soldiers to be immune from prosecution

To those of us from Northern Ireland, the past can’t just be brushed aside

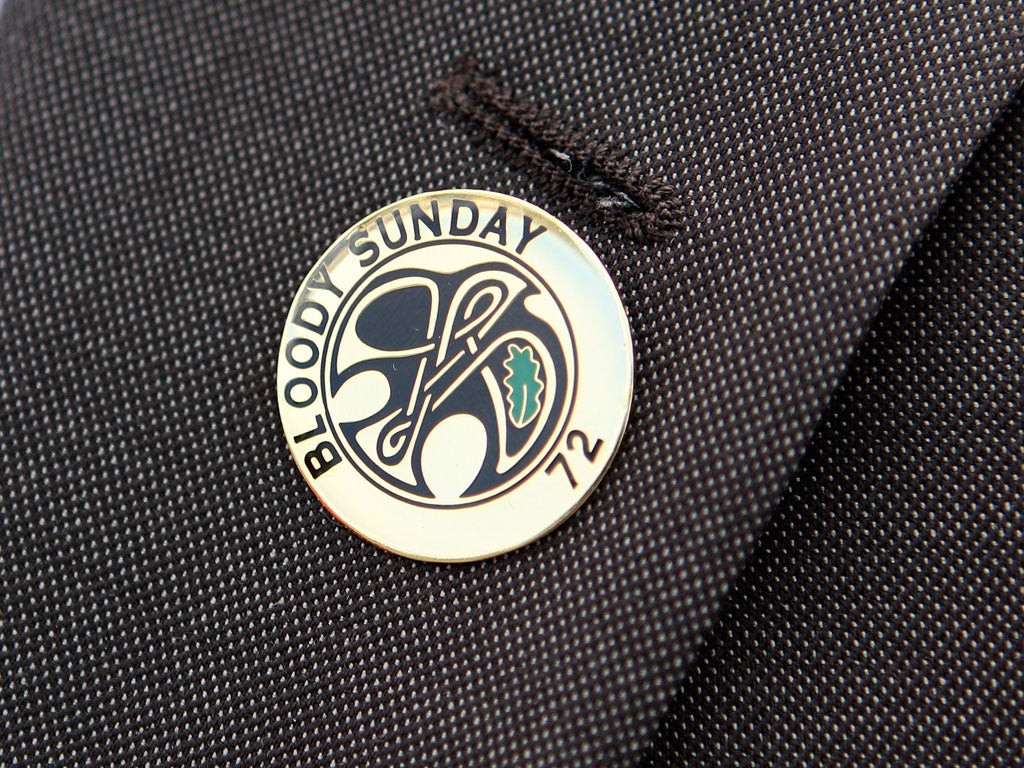

I’m sure that other than in North Korea politicians aren’t supposed to step in and stop police investigations. Yet Peter Hain yesterday stated that it was a waste of police time and money to investigate the soldiers involved in the Bloody Sunday atrocity. Writing in the Sunday Telegraph, he defended the “On the Run” letters that provoked such a wave of controversy last week – and in doing so, used the moment to put up an idea he has long held dear: paratroopers who killed 14 people in the Bogside in Derry on 30 January 1972 (13 on the day, one of injuries later) should not be charged for their crimes.

Why is Peter Hain trying to circumvent justice? One clue: he wrote that the north of Ireland “looks over its shoulder too much at the past, rather than to the future”. It is this metaphor that I think reveals his perspectival error. When you live in Northern Ireland, the past is not behind you. It is in the soil beneath our feet. And beneath the surface grow the shoots from seeds planted years before.

Yes, there was a peace process. Yes, there was an agreement on a Good Friday that war should cease. It wasn’t just a war on two fronts, though. And so the agreement wasn’t the end of fighting and the beginning of peace. It was a line drawn in the history books, a line of pebbles on bloodied soil that said “this far and no further”. To get all those pebbles in place was a feat of delicacy and compromise from political factions and terrorist splinters and political parties and communities and groups; voices clamouring from all sides about how and where the stones should be placed, what they’d do to lend their support and what they wouldn’t.

It was complicated. To get to that point required multifarious bargains, conversations through the night, deals made in alleyways, the prayers of church leaders, winks and nods to the deadliest of perpetrators, and declarations of forgiveness from families whose sons and daughters died horrible deaths.

But new beginnings do not negate the past. They cannot. To imagine that they do is to imagine that there are no consequences. And to believe that there are no consequences turns the peace agreement into a PR exercise, a shiny plastic floor tacked into the soil, with no foundations, no strength or stability to deal with what inevitably comes up from the soil beneath.

The On the Runs letters pushed their way up above the surface last week, dislodging the plastic boards that the Northern Ireland politicians are standing on. The revelations shook the NI government, with first minister Peter Robinson threatening to resign. That’s what happens when you pretend the past didn’t happen. This is why Peter Hain is incorrect.

The Saville Inquiry, which ended in 2010 after 12 years, concluded in gut-wrenching terms that the battalion sent into the Bogside was at best off-message, and at worst, out of control. David Cameron, in response, apologised: the murders were “unjustified and unjustifiable”. The Inquiry presented prima facie evidence that individual soldiers had committed crimes. And so, in a step of logic that should not be questioned, the Police Service of Northern Ireland is in the process of doing what is surely a norm for police forces: to detect and investigate crime.

Fresh posters have been put up in Derry, calling for witnesses, and paratroopers involved have received letters asking them for questioning. One paratrooper spoke out yesterday, railing against the “injustice” that would see him questioned, but would see terrorists given amnesty. But how can justice be served if a terrorist and an employee of the state are given an equal level of accountability?

Peter Hain says that people look too much to the past. But Bloody Sunday is an open wound. And the feeling on the ground in Derry is one of deep suspicion. Never mind that people think that the fresh investigation is a mere publicity exercise, people in the Bogside, aren’t trusting of the “comfort letters”.

At some point, when there has been a war, you get over certain things. It has been difficult for some groups to reconcile that Martin McGuinness is now in power. But things move on. And less violence and more diplomacy is progress. When I go back home, Belfast is different from when I was growing up. There were bag searches in shopping centres. Army vans trundled down the streets. Machine guns were part of routine police wear.

It’s better now: the outer dimensions of life in Northern Ireland are changing. But the past happened. And like bindweed, you can’t keep chopping down the stems that pop up above the surface, because that way you’re not dealing with the problem. What’s beneath the surface will just spread out, become more gnarled and tangled. The consequences of war are knotty, difficult to handle, thorny and bloody. But they must be faced. They must be unpicked. Or there will be no chance for anything new to grow.

@claredwyerh

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks