Robert Fisk: Britain feared civil war in Ireland more than it feared war in Europe 100 years ago

Was the British Empire about to crumble from within? This was the question at the start of 1914

When I was researching the execution of Chinese workers employed by the British on the Western Front of the Great War at the Public Record Office, I found, among the papers, the official notice of the death by firing squad of Padraig Pearse and the other “rebels” of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. Pearse and his brother Willie, and Connolly and McBride and the other 10 men put to death in Dublin on the orders of General John Maxwell, were deemed worthy of capital punishment in the 1914-18 war. Their papers lay in the very same file as those of British soldiers shot for desertion or cowardice in France. For the British Army, the Easter Rising was just another episode in the Great War.

I recalled all this last week when I walked past the central redoubt of the 1916 insurrection, the General Post Office in O’Connell Street in central Dublin, its walls still scarred by a few bullet holes; another bullet – probably British – left its hole in the left breast of a bronze angel guarding O’Connell’s statue beside the River Liffey. And when I turned into Lower Abbey Street, I walked past Wynn’s Hotel where the Irish Volunteers – who were to fight in the Easter Rising and are the forerunners of today’s Irish Army – held their first meeting on 11 November 1913.

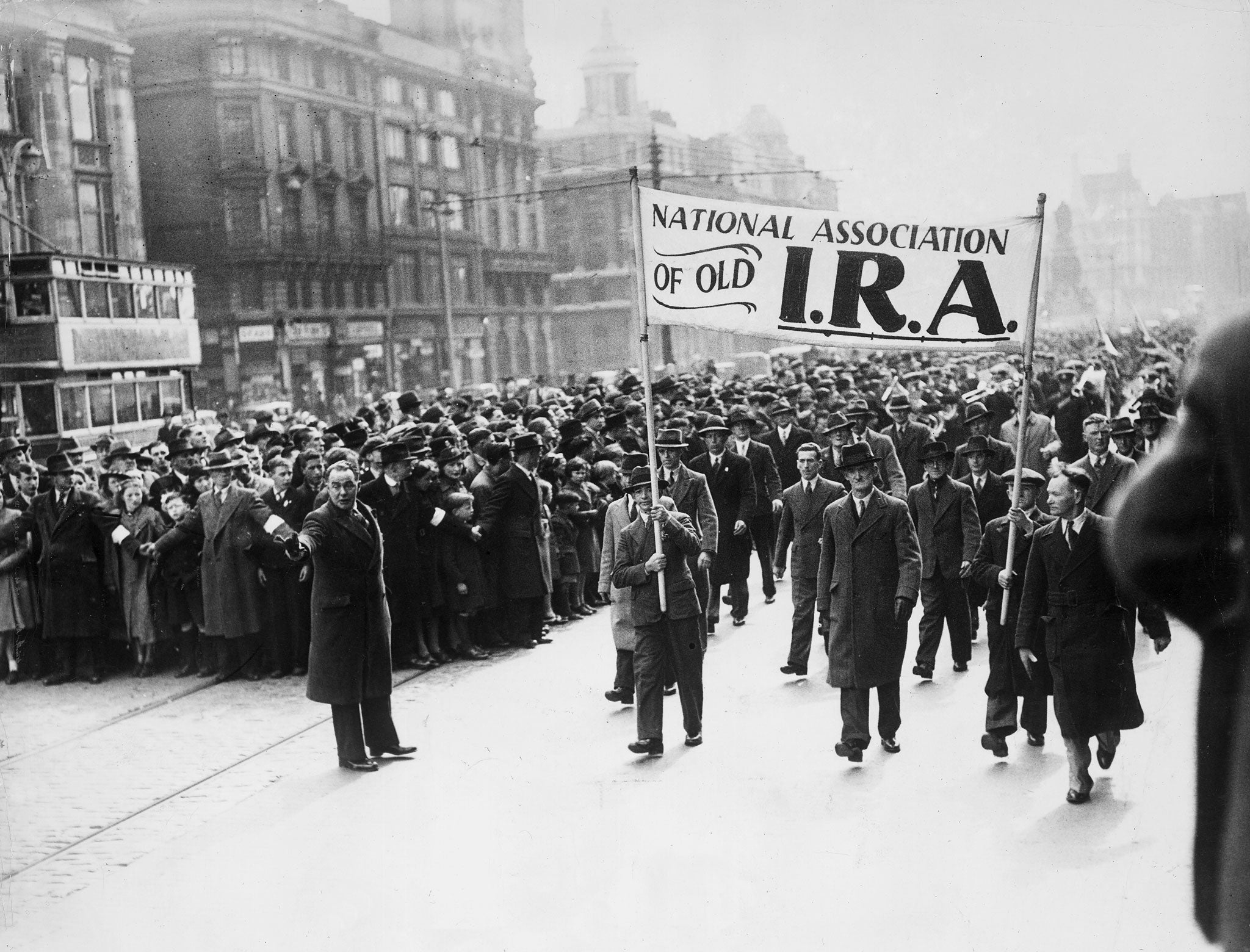

Astounding it is to recall now that this event (partly in response to the creation of the armed Protestant Ulster Volunteers) and the civil violence in Dublin and other cities at the time consumed British politics on the eve of the Great War. Civil war in Ireland – not war on the continent of Europe – is what London feared 100 years ago. Would the British Army mutiny if ordered to force the Protestants of Ulster into Home Rule? Was the British Empire about to crumble from within? This was the question at the start of 1914.

And could I not sense this a few metres away from Wynn’s – still, by the way, a hotel – where the Abbey Theatre was last week staging another version of James Plunkett’s The Risen People. A collection of stories on the 1913 Dublin lockout by Jimmy Fay from a version by Jim Sheridan with characters from Plunkett’s original Strumpet City, it told the story – from the workers’ point of view – of the great anti-trade union struggle of William Martin Murphy, an immensely wealthy Irish businessman and owner of the Irish Independent newspaper, who colluded with other employers to refuse work to anyone joining Jim Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers Union. Up to 100,000 Irish men and women were put out of work in a city of 305,000 people, of whom 87,000 lived in tenements and where infant mortality was the highest in Europe.

For the British – who still owned Ireland – the lockout was symptomatic of the growing nationalism of the island, even though the industrial struggle was between Irish workers and employers. British trade unions offered funds to their Irish brothers and sisters – and even temporary homes for their starving children. But the Irish Catholic Church, opposing such assistance on the grounds that the children of the poor would be in the care of English Protestants, persuaded their flock that it was better their progeny should starve in Dublin than receive three meals a day in England. The Risen People contains songs aplenty – not least the Communist Internationale – but the one trade union official who is asked to sign an employer’s document promising to abandon Larkin’s union in return for work, burns the paper in 1914 – and joins the British Army.

So at the end, he is presented with his military webbing, khaki uniform, Lee Enfield 303 rifle and steel helmet, and sent off to Flanders. The lockout lasted for eight months – whether the employers or their workers won is still debatable – but the hero who should have benefited from a good life in his own land leaves for an inevitable death on the Western Front – in British uniform rather than that of the Irish Volunteers who first met round the corner from the Abbey.

Not so surprising, though, when you remember that Irish parliamentary leader John Redmond – promised that Home Rule would be passed at the end of hostilities – urged the Volunteers to take Britain’s side against Germany. Upwards of 170,000 answered his call, but among the Volunteers’ leadership were those who believed, after the trenches of France had smothered hopes of an early end to the war, that England’s difficulty was Ireland’s opportunity.

Thus one side in the putative civil war which dominated the British empire in the early months of 1914 took up arms against it two years later. For the British, who had gone to war for the freedom of little Belgium, the firing squads of 1916 were a mere footnote in the Great War. For the Irish, they were the start of the final struggle for the freedom of another little country. And just over two months later came the Somme.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks