Sorry James Salter, if a book's any good, the best lines will linger. And you can quote me on that

Plus: The joke's on the National Gallery and fangs a lot to the film funders

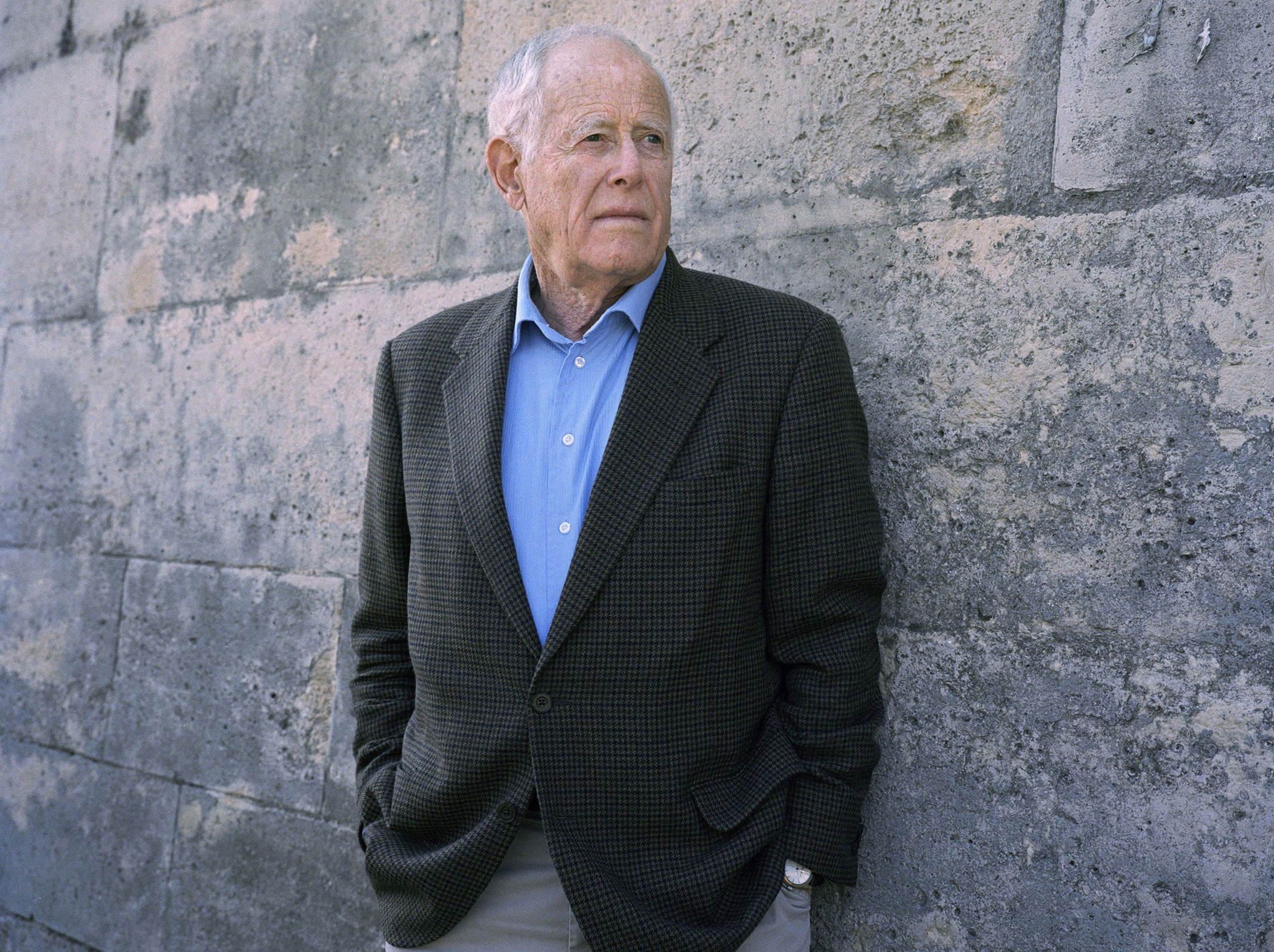

"I wanted to write a book where nobody underlines anything on any of the pages," the writer James Salter said in a recent interview with Esquire magazine about his novel All That Is. "I don't want it to rely on language or for the language to be conspicuous."

His ambition is ambiguous. There are two ways of achieving it, after all, one considerably harder than the other. Either you make the book seamlessly bland and uninflected, or you achieve such a steady state of excellence in the writing that no one sentence stands proud of the next. Salter explained – a little immodestly to be honest – that the ambition had come about because he "was constantly hearing people talking about their favourite passages" with his previous book.

Having read All That Is I found myself wondering whether what Salter was really objecting to was the conversion of his writing into "quotes" – that dismemberment from context which is a hazard for all writers, and which brings with it the faintest odour of the fortune cookie. It's one thing to have a line quoted as evidence of your prose style, after all, and quite another to have it served up as a free-standing quote – a truth about the world which doesn't require the substantiation of what went before or after.

One of my own favourites – at the risk of irritating Slater – occurs on the first page, where he describes dead soldiers "lolling in the surf, the nation's sons, some of them beautiful." The patriotic cliché includes everyone and then the last four words discriminate – in circumstances where discrimination seems almost like an affront. What could looks possibly matter? And yet the human mind still distinguishes.

It's not the only quotable line in the book – but the odd unfinished nature of that last phrase, as if it was thinking of explaining itself but then decided against, withdraws some of the endstopped satisfaction of the over-neat quote. Which doesn't mean that Salter has achieved his ambition. What's really odd is that there are lines in the novel which seem almost designed to hook you to a stop like an aircraft carrier arrestor wire. Salter seems preoccupied with the capacity of his central character's ejaculations – directly addressed twice in the book – and on the second occasion he uses this unexpected metaphor: "The silence was everywhere and he came like a drinking horse". So startling is the line that its fame has gone before it. On Twitter someone even posted a YouTube video of a drinking horse so anyone interested could venture a more direct comparison.

There was debate about what exactly was meant. Drinking horses don't sip, so presumably the image aimed at something impressively copious. A sense of hydraulic vigour couldn't be entirely ruled out either, though a horse's gulping absorption of fluid seemed 180 degrees at odds with what was being described. I wondered for a while whether it was simply the unstoppability of the moment that attracted Salter to the metaphor. I don't have much experience of drinking horses, but I imagine if the animal is thirsty it's no easier to interrupt in mid-flow than an ecstatic climax.

My guess was that this wasn't one of those moments when a writer casts around for the perfect image and finds it but that Salter had seen a drinking horse at some point and thought to himself, "that looks oddly familiar... must use that one day". In a sense it was underlined already, by Salter himself.

I can't get it out of my head now, anyway, and can't look at the book without thinking of it underlined so forcefully that the next three pages are indented too.

The joke's on the National Gallery

Michael Landy's exhibition Saints Alive, which transforms National Gallery saints into clanking self-destructive automata, is probably the funniest exhibition ever staged in the Sunley Room. But I did find myself wondering whether its comedy would leave a permanent mark on the collection. After seeing Landy's St Francis, who whacks himself on the head with a crucifix when you drop a donation in the box he sits on, it's difficult to look at the original painting without a memory of slapstick. And I'll never be able to look at Carlo Crivelli's Saint Lucy in the same way again, having been alerted by Landy to the bizarre comedy of her pose. It's as good as the Muppets.

Fangs a lot to the film funders

"Remember. The revolution started here," said Stephen Woolley, introducing a gala screening of Neil Jordan's new vampire film Byzantium the other night. He wasn't actually referring to the film (excellent, by the way) but Jordan's success in persuading all the funders to show all their vanity cards on a single montaged screen.

Instead of six of those swooshy CGI graphics that clutter up your pre-film anticipation, there's just one brief screen showing the logos of the production companies.

And then the director gets to have a crack at your perceptions, refreshingly unpolluted by corporate showboating. I don't know how he did it – but I really hope the trend spreads.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks