The Japanese torture of my father was horrific — so why are they considering watering down the apology for their wartime past?

Around 80,000 allied troops were captured by Japan in Singapore, and suffered some of the worst treatment imaginable

The Japanese have always had a problem admitting they did anything wrong during the Second World War or during their long colonial rule in Asia.

So it's sadly unsurprising that their Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, has just announced that he is considering watering down the country's 1995 apology over its wartime past, “for waging aggressive war and oppressing its neighbours”. Abe has appointed a panel of experts to consider for the first time what he should say at ceremonies to be held to mark the end of World War Two, to coincide with the 70th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day.

This is despite opinion polls suggesting that most Japanese people feel that their country did things in Asia for which the country should apologise. But there are some, like Abe, who are obviously blinded by their nationalistic pride, or uncertain about how appropriate the apology is now so much time has passed.

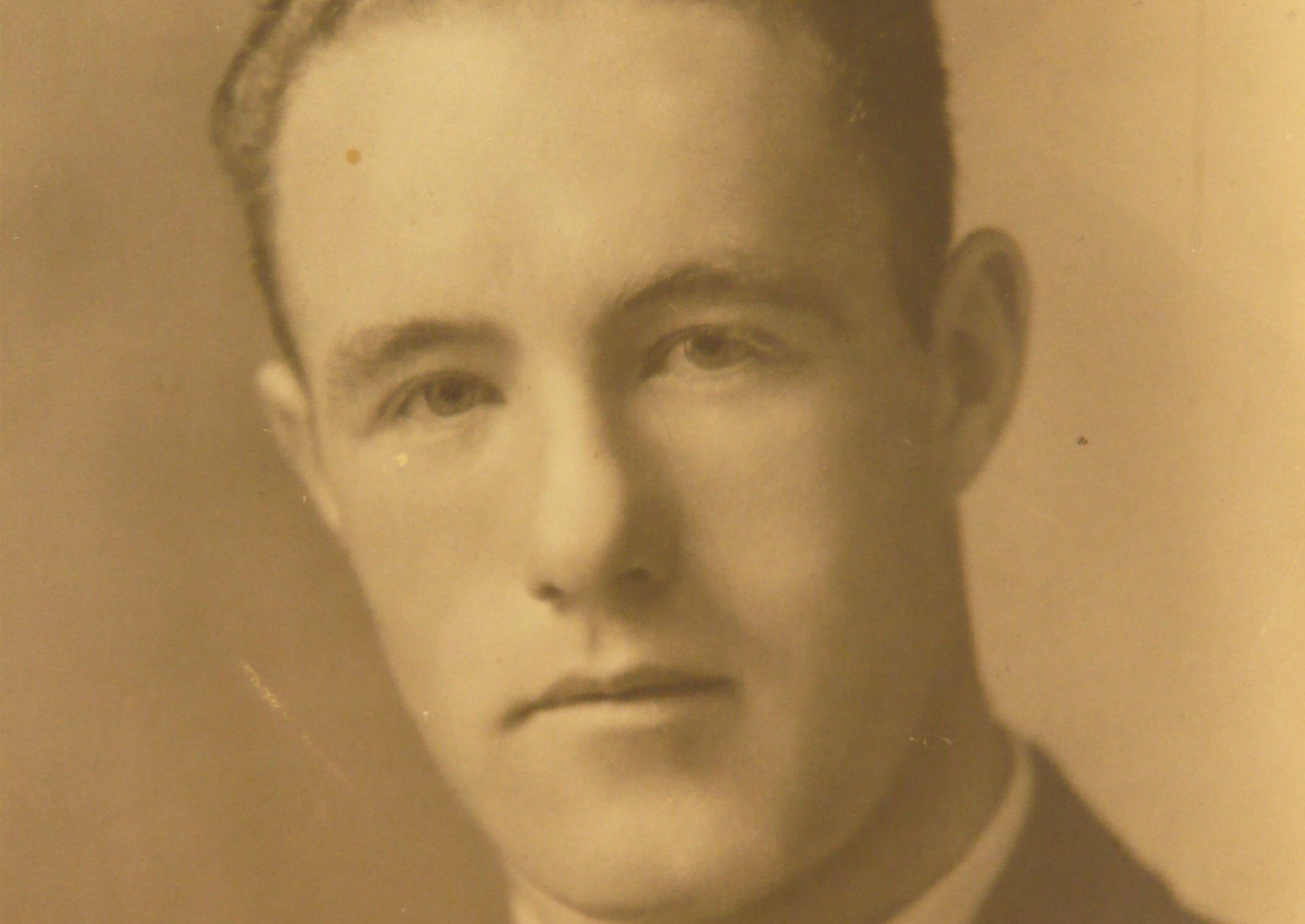

For surviving Far East Prisoners of War (FEPOWs) there are no grey areas. My father was a Japanese Prisoner of War in Java with all the horrors that entailed. As a Canadian member of the RAF, Wing Commander William Woods fought in the Battle of Singapore, as part of the allied forces' Far East Campaign. He was in charge of 100 men when they were captured in 1942 by the invading Japanese army, and was moved to one of the largest POW camps on Java.

Churchill called Japan's capture of Singapore the “worst disaster” and “largest capitulation” in British military history. Around 80,000 British, Indian and Australian troops based there became POWs as a result.

Once taken prisoner, my father was subjected to the most horrific torture. Torture which included being staked out in the midday sun with a glass of water just out of reach, to routine beatings and operations without anaesthetic.

Some prisoners even told stories of being forced to drink pints of water, being tied to the ground and then having gleeful guards jump on their stomachs.

My father spoke of the terror when the Kempetei (the Japanese equivalent of the Gestapo) would arrive at the camp and scream out the names of ten men who were then ordered outside to dig their own graves. Nobody knew who would be called next-all they could do was listen to the shots being fired and the thud as the men fell.

Prisoners were starved of food and the camps were rife with cholera and dysentery. My father once told me he would eat anything he could find including frogs, spiders and snakes.

When Victory in Europe Day arrived in May 1945 it may have signalled the end of the war in Europe. But as thousands thronged the streets in celebration, many prisoners including my father were preparing themselves for what turned out to be three more long months of suffering. During that period many more prisoners were slaughtered in cold blood by the Japanese.

When the Americans finally liberated the camps, they faced a vision from hell, as they were greeted by thousands of skeletal men with sunken eyes and broken bodies. Many of these men could not cope with “normal” life on return to the UK and simply dropped dead. Many who survived, like my father, never recovered psychologically.

The trauma my father experienced damaged him for the rest of his life. When he returned he was skin and bone. At six foot he weighed little more than 6 stone. When my mother received the news she had waited three and a half years to hear she went to meet him off the train. She walked past him twice on the platform before she recognized him.

He lost his Catholic faith and indeed his faith in the whole of mankind. Once home, he was prone to long bouts of deep depression and terrifying nightmares which frightened my mother and had a tremendous impact on our family. But he could never bring himself to talk about the horrors he had witnessed.

The war in the Far East is often called the Forgotten War — not helped by the many years it took to get the Japanese to apologise for the part it played. Even now some Japanese, just like Holocaust deniers, still believe that accounts of Japan’s wartime atrocities were lies or gross exaggerations. Japanese children are taught very little about this part of their history.

When an apology did finally come it was too late for my father —he died 21 years ago, a year before the apology was issued. However, there are still survivors of those camps for whom it would be a terrible insult to hear Japan rethinking its stance.

China and South Korea are not happy about his plans to rethink the apology. China has warned Japan not to “whitewash past crimes of aggression” while South Korea has said that any statement should not “row back from past apologies”.

The debate shows the huge divide that remains in Japan 70 years after the war ended. On the one side there are the denials of any wrongdoing and on the other those who say the country should never forget how it invaded Southeast Asia and the disaster that arrived in its wake.

For my part those men who were captured and so brutally tortured should never be forgotten; Japan must face up to its past actions and leave the apology as it is. And I'm sure that if my father was alive he would agree.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks