There has been no good news for Britain’s army of underemployed workers

The underemployment rate rose more quickly than the unemployment rate in Q1 2013

The latest growth estimate – 0.6 per cent for the second quarter of 2013 – is better than we have seen for a while. The last time there was anything like that was in the third quarter of last year when there was growth of 0.7 per cent, which was all down to Labour’s investment in the Olympics and illustrated the point that public investment generates growth. Before that, there was growth of 0.6 per cent in Q3 2011, which was followed by growth of -0.1 per cent, zero and -0.5 per cent. So hang on to your hats, folks, there is likely to be a bumpy road ahead. Indeed, most forecasters are expecting little or no growth over the second half of the year.

The economy has only grown 1.8 per cent in total over the last 11 quarters, against 2.3 per cent from Q3 2009 to Q3 2010. Indeed, the 0.6 per cent is only the third quarter out of the last 11 that matched the rate of economic growth that George Osborne inherited. Recent work by Alan Taylor from the University of California, Davis has shown that without the Chancellor’s austerity programme, output would be 3 per cent higher – almost back to the starting level of output. Professor Taylor argues that there are plausible grounds for arguing that Mr Osborne has had an even bigger downward effect.

The Chancellor claimed last week that Britain is now “on the mend”, but this may well only be a temporary recovery from a self-inflicted wound and one for which he really can’t take credit.

There is little evidence that this growth rate is sustainable, especially as business lending still continues to fall, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Newly published evidence by Bob Butcher and Matt Bursnall* suggests the net reduction in jobs in 2008-11 was not, in contrast to earlier recessions, due to higher rates of job loss; instead it reflected a sustained period of lower job creation in workplaces, especially among SMEs. This is consistent with ongoing credit constraints hitting SMEs particularly hard. There is no evidence that this has changed.

Other evidence on the labour market is hardly consistent with sustained recovery. We should expect the unemployment rate to rise next month. Currently, the published rate for March-May is 7.8 per cent, made up of one monthly average of 7.4 per cent and two of 8.0 per cent; next month the 7.4 per cent will be dropped. A similar story applies to employment; the last three monthly observations have been, in thousands, 29,828, 29,740 and 29,574, and next month the big one is going to be dropped.

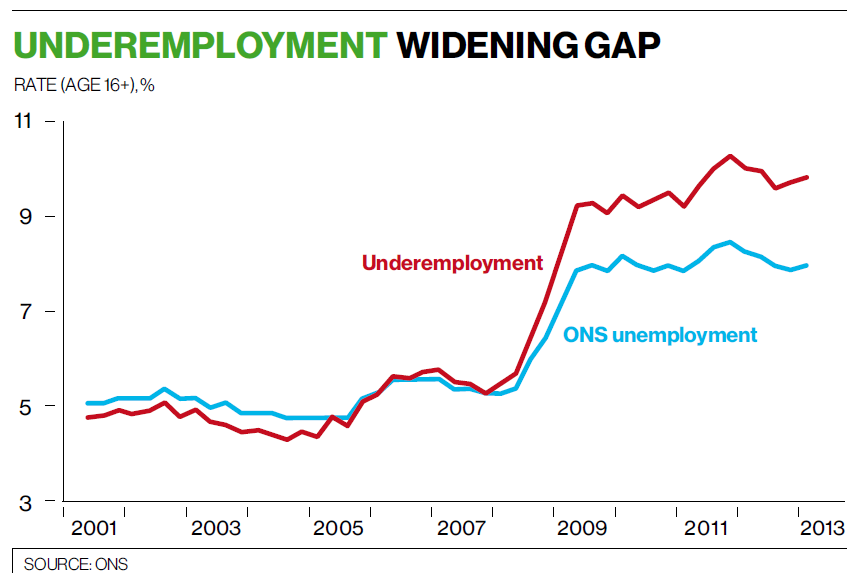

David Bell and I have now updated our underemployment series, which is presented in the chart above. It is a new measure of labour market slack. The conventional measure of the difference between supply and demand in the market is the unemployment rate. We have now updated our figures to the first quarter of 2013 and seasonally adjusted them.

Underemployment continues to rise: our latest estimate shows that the seasonally adjusted gap between the UK underemployment and unemployment rates rose over the quarter from 1.89 per cent to 1.94 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. This compares with 1.07 per cent at the start of 2009 and 1.79 per cent a year ago. The increase is due to the widening gap between the hours that employers are willing to pay for, and the hours that UK employees wish to work. The likelihood is that this is due to falling real wages.

British workers said they wanted to work a net extra 19.9 million hours each week compared with what their employers were offering, up from 19.1 million a quarter ago – obtained by summing the hours of those who wanted extra hours and those who wanted fewer. Given that the average working week is 32 hours, this is equivalent, approximately, to an additional 625,000 jobs.

The British labour market has changed. Although unemployment rates are broadly comparable with those of the 1990s, those in work now are significantly more likely to want to work more hours than their employer is willing to offer. There has been a shift in emphasis from an excess supply of people to an excess supply of hours.

Large numbers of workers want to increase their hours and are willing to do so without any increase in their hourly wage rate. Of course, some would like to work fewer hours. We take account of this in our underemployment measure. There was no change in the aggregate desired reductions in hours worked in the first quarter of 2013. Because the gap between aggregate desired increases and aggregate desired reductions widened, the underemployment rate grew more quickly than the unemployment rate in the first quarter of 2013. No sign of recovery here.

Hours constraints do not augur well for consumption. Why would the consumer spend if their incomes are constrained and savings can only last for so long? Of particular concern is that this underemployment affects the young especially. The gap between the underemployment rate (29.8 per cent) and the unemployment rate (20.4 per cent) for those under the age of 25 is huge. It contrasts with a much smaller gap for those aged 25-49, who have an unemployment rate of 6.36 per cent and an underemployment rate of 8.3 per cent. Meanwhile those aged over 65 want fewer hours –many would like to retire or go part-time. So older workers have more hours than they want and younger workers fewer hours than they want. It shouldn’t take a genius to see that there may well be benefits from trade at a time when the Youth Contract looks like a youth “con-trick”.

The big concern down the road is that the insiders take all the work in a recovery at the expense of the outsiders, namely the young unemployed. If that happens, hours rise but employment doesn’t rise in proportion and unemployment doesn’t fall. The average duration of unemployment also continues to rise, with harmful scarring effects. So much for the good news.

*Bob Butcher and Matt Bursnall “How dynamic is the private sector? Job creation and insights from workplace-level data”, National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks