We’re on a very slippery slope if we accept what Clean Reader is trying to do

Removing “unacceptable” words cheats both the writer and the reader

When I was bullied at school (which was often), my grandfather used to say this to me: “Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” He was wise in many ways, but in this I think he was wrong. Words are far more potent than any kind of weapon. The world still reels from the impact of Shakespeare; the Brontës; Nabokov; Joyce – words written by people long dead, but whose voices ring true, even today.

As a writer as well as a linguist, I am very much aware of the potential impact of my words. I choose them with care, reading aloud to check the tempo of the phrase. Where I can, I work with my foreign translators to try and ensure that the music, as well as the meaning of words, is conveyed as cleanly as possible.

Sometimes, I meet an obstacle. When my books are edited for release in America, I often find myself having to fight to retain my “British” vocabulary; my Oxford commas; my rhythms and sounds; my idiomatic phrases. But to try to convert my accent into an American drawl; to substitute sidewalks for pavements, or eggplants for aubergines, seems both clumsy and pointless. I want my readers to hear my voice, not a synthetic version, and if that means including a few footnotes to explain some of my more arcane vocabulary choices, then so be it. Words are our weapons; without them, we are mute and defenceless.

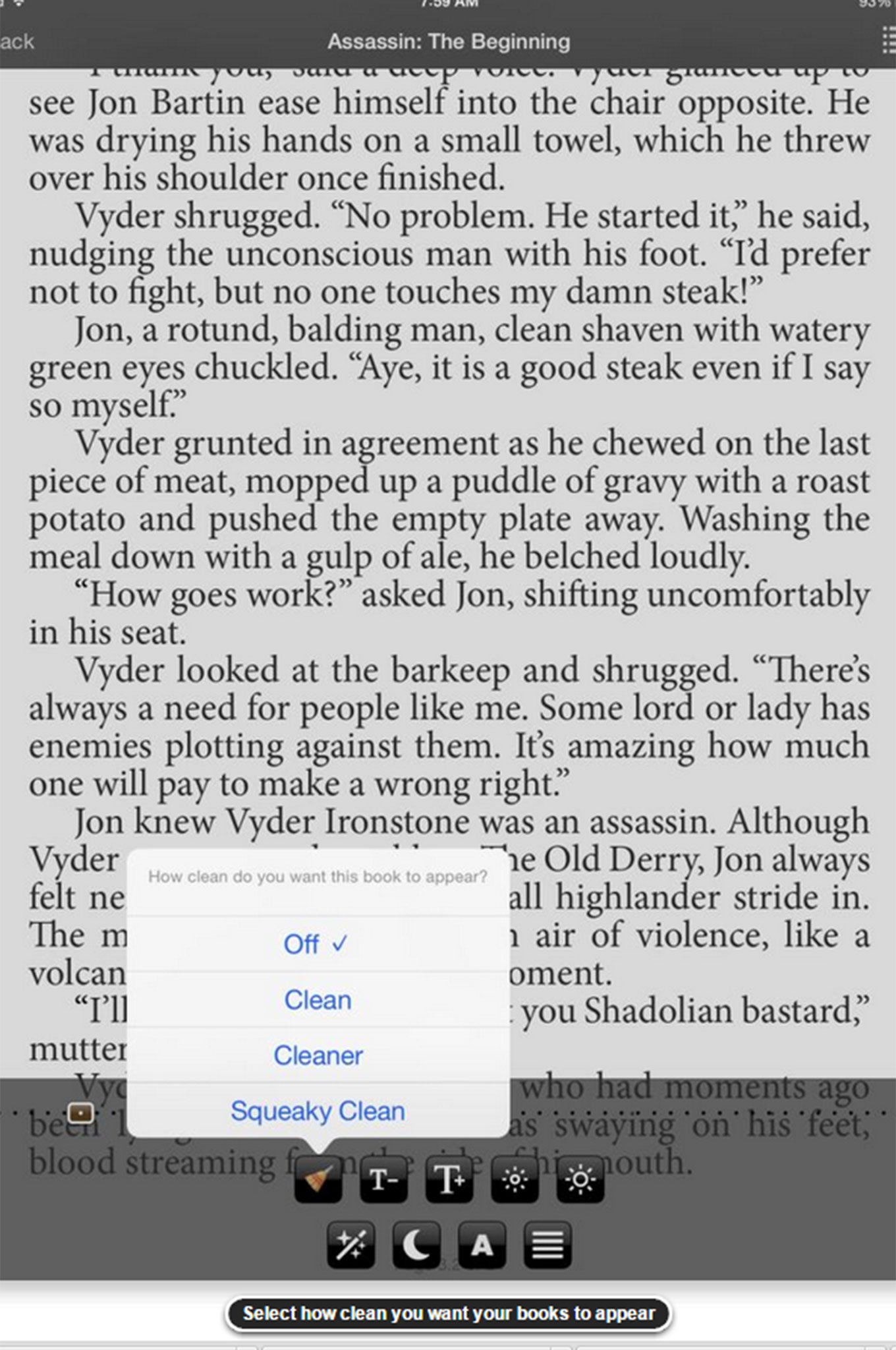

The book world just saw the launch of an app called Clean Reader, which claims to remove profanity from e-books, by either blanking out the offensive word, or replacing it with an “acceptable substitute.” At first sight, this may not seem an entirely unreasonable idea; not unlike the programs used by parents and schools to ensure that children are not exposed to unsuitable material online. But closer inspection of the idea shows how problematic it is.

First, the “acceptable substitutes.” These are all modern American terms, (“Geez” for “Jesus Christ”, “freaking heck” for “fucking hell”) and not only do these verbal fig-leaves make nonsense of the original material, their presence is likely to be far more intrusive. Authenticity, meaning, style – not to mention the author’s intention – are thrown onto the rubbish-heap by this mean-spirited, hypocritical device.

Body parts have often been the target for censorship, and the makers of Clean Reader seem not only determined to remove all mention of them from your reading experience, but also to make it as difficult as possible to distinguish one from the other. Therefore, “vagina”, “anus”, “buttocks” and “clitoris” all translate as “bottom”, which seems not only ignorant, but also potentially harmful. If, as the makers of Clean Reader claim, this is a move to protect young people, then I would suggest that teaching them to be ashamed of their bodies and to believe that sex is wrong is far more damaging than simply exposing them to profanity. Children swear at school, after all – but I doubt they learn those words from book.

As it happens, I don’t use profanity very much in my novels at all. When I do, it has an impact – an effect I deliberately set out to create. The pursuit of authenticity in dialogue or narrative voice means that the readers may sometimes encounter language they might not wish to use themselves. Some people are very sensitive to this kind of language – in which case, I would perhaps advise them to avoid the novels of Irvine Welsh, and although I feel it would be their loss, I would support their right to choose whether or not to read his books.

But Clean Reader gives no rights to the authors whose work has been mangled. Our consent is neither sought, nor considered relevant. Working from a perspective that considers individual words to be more important than the ideas they represent, the makers of Clean Reader have taken it upon themselves to rewrite literature according to their narrow-minded view. After pasteurisation by Clean Reader, Shakespeare, Chaucer, Lawrence and Joyce will all sound like members of the Mickey Mouse Club. Larkin’s poem will begin: “They freak you up, your mum and dad.” And God knows what the Song of Songs will become, once all the breasts have been changed to “chests.”

So what, I hear you ask. Surely readers should be free to do what they like with the books they’ve paid for. Well, yes. To a point. But, as in all relationships, consent matters. The relationship between a writer and a reader is no different. I would rather see my books withdrawn than see my words altered without my consent.

Anyone who works with words understands their power. Words, if used correctly, can achieve almost anything. To tamper, without the author’s consent, with the work that they have published – however much we may dislike certain words and phrases – is an affront both to art and free speech, and encourages censorship of the most insidious kind.

Britain’s Reformation brought about the destruction of over 90 per cent of our country’s art heritage, including music, books and paintings. The Victorians bowdlerised and rewrote Classical myths and literature out of all recognition. The Nazis burnt countless works of art judged to be “degenerate”. Isis are currently destroying antiquities and historical sites in the Middle East. And all in the name of purity, morality and good taste.

We’ve been down this road before. We should know where it leads. It starts with blanking out a few words. It goes on to drape table legs and stick fig leaves on statues. It progresses to denouncing gay or Jewish artists as “degenerate”. It ends with burning libraries and erasing civilizations. Is that where we want to go again? Not. Fucking. Likely.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks