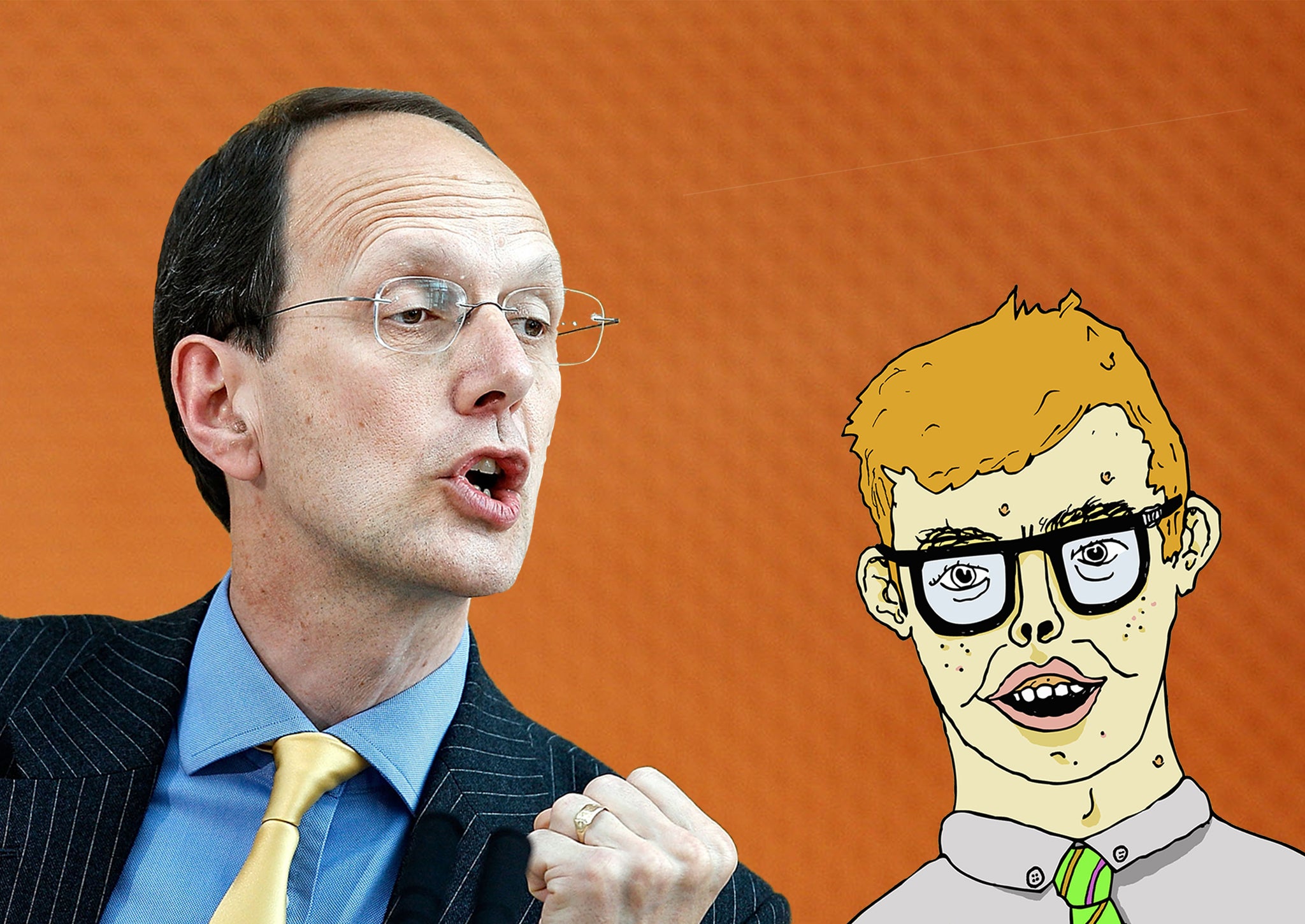

Yes John Cridland, 'spotty nerds' are the video game industry's biggest problem...

As a female video games writer, it's hard not to laugh at how outdated his views are

I am a spotty nerd.

At least I am according to John Cridland, Director General of the Confederation of British Industry. You see I work in videogames. Yes, that multi-billion pound industry which regularly eclipses box-office and music sales. But the trouble is, according to Cridland, who recently advocated the inclusion of arts subjects alongside traditional STEM subjects in school that: “Nobody is going to buy a game designed by a spotty nerd.” Considering worldwide game sales are expect to reach $102.9 billion by 2017 I’d say that we’ve been doing pretty well so far.

There has been much tittering about such a dated insult. For years now the industry and gamers alike have reclaimed and repurposed the term "nerd" into something that personifies passion and determination. Like the A-Team locked in a toy warehouse, we took a load of disparate parts and emerged in a tank.

Stereotypes aside, Cridland believes an influx of artistic and creative types are exactly what games need in order to boldly move the industry forward, presumably without Clearasil. This is great news because I happen to be a video game writer – both the sinner and the saint in Cridland's black and white world. I am both “nerdy” and creative. I am the answer to my own problem.

But what Cridland apparently fails to grasp is that creativity and videogames have long marched hand-in-hand. Musicians, artists and even writers have been a part of games development for decades.

Leaving out the more traditional artistic fields for a moment, game design alone is an incredibly creative undertaking. Mechanics, level- design and gameplay are all vital to the gaming experience. They support the unique and powerful interactive journey players undertake when they fire up a game. For example, the indie title "Papers, Please" puts you in the jackboots of a beleaguered border control officer in a fictional communist country. Meanwhile, the blockbuster title BioShock sees players journey through a fallen utopia frequently holding the fate of children in their virtual hands. Both titles show how game mechanics can be not only entertaining, but emotionally engaging.

Cridland does have a point though: traditional artistic fields would benefit from more support. Across the board, the quality of narratives and scripting in video games is still developing. This is after a bit of a chequered history, in which it has lagged behind other entertainment in both breadth and depth. Now it’s becoming a field that attracts talent like Alex Garland, whose work has been recognised at both the Writers’ Guild and BAFTA awards for video games.

That said, the call for more general “creativity” also over looks one key issue. The search for a more diverse workforce is also something the industry desperately needs to embrace if it’s to generate fresh ideas and perspectives. A US-based survey in 2014 by the International Game Developers Association estimated that Caucasians dominate 79 per cent of the industry, with Hispanic/Latinos at 8.2 per cent, followed by East/South East Asian at 7.5 per cent and Africans/African Americans at 2.5 per cent. Likewise women only make up 22 per cent of the workforce, although this figure has doubled since 2009.

The Lady Geek, a company that was the first to measure empathy in business with a new index, has an initiative called Little Miss Geek (LMG). By working with young women, they try to better educate them about the opportunities for them in the games industry. During their research they found that the perception of the industry often revolved around it being purely a hard science world and, unless you were into those subjects, there was no place for you.

LMG’s game design workshops help open girls’ eyes to the fact that art and creativity do already play a huge part in game development. The results are like pointing them towards a wardrobe and watching them emerge into Narnia. They discovered a wonderful and exciting new world.

Some of them may grow up to have spots. Some of them may be a little bit nerdy. But who cares? If nine-year-olds can have their eyes opened to the chances that currently exist within the games world, then perhaps Mr Cridland can too.

Rhianna Pratchett is writer and narrative designer for videogames, comics, TV and film. She’s worked on titles such as: Tomb Raider, Heavenly Sword, Mirror’s Edge and the Overlord series.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks