Review of the year 2009: Expenses scandal

They’ll have to get used to life in the duck house

British politics in 2009 should have been dominated by "the economy, stupid". Yet that was probably eclipsed in the public mind by another crisis, over MPs' expenses. The implications are huge. The economy will recover, but the reputation of our politicians will take much longer to restore.

Handling the two big domestic crises at once took a heavy toll on the Government. And that was before the Afghanistan election set the cat among the pigeons. No wonder Gordon Brown's ratings suffered.

They were not the only victims. Michael Martin became the first Commons Speaker to be forced out of office for more than 300 years. He was a symbol of the forces of conservatism that ran Parliament like a cosy club and failed to acknowledge the need to change when the expenses bomb detonated. He was replaced by John Bercow, a Tory voted in to office on a reform ticket by Labour MPs. Bercow described the expenses scandal as doing more damage to Parliament than anything in recent history "with the possible exception of when Nazi bombs fell on the chamber in 1941".

This year's casualties included four MPs and peers under investigation by the police, and whose cases have already been referred to the Crown Prosecution Services. There are more criminal cases in the pipeline.

Others fell victim to disciplinary action by their own parties as leaders tried desperately to reassure angry voters that they recognised the scale of the problem. Ian Gibson, an independent-minded Labour MP barred from standing at the next election, resigned in protest, causing a by-election in Norwich North, which Labour duly lost to the Tories.

Many other MPs decided to stand down of their own volition. More than 50 have announced their retirement since the controversy began, and there will be more. Some would have quit anyway. Some jumped before they were pushed, others were deeply disillusioned about the rough justice meted out to MPs caught in the storm. Others feared the hastily cobbled together reforms to clean up the system, although necessary, would change Parliament for the worse and no longer wanted to be part of it. Whatever the election result, the expenses affair will help to ensure an unusually high turnover of MPs, almost certainly the biggest since 1945.

Even those MPs who think there was an over-reaction admit the political class only has itself to blame. An attempt to make expenses claims exempt from the Freedom of Information Act was always likely to end in failure. The tradition of bumping up allowances and encouraging MPs to claim them in full, dating back to the 1970s, was a way of avoiding controversy over paying MPs a sensible rate for an important job. It, too, was bound to be exposed in a digital age demanding more transparency and accountability.

The expenses controversy could have been handled better by the politicians when it erupted on the front page of The Daily Telegraph in May with a story revealing Brown's claims for cleaning his second home. His response was to berate Will Lewis, then the paper's editor, in a long telephone tirade.

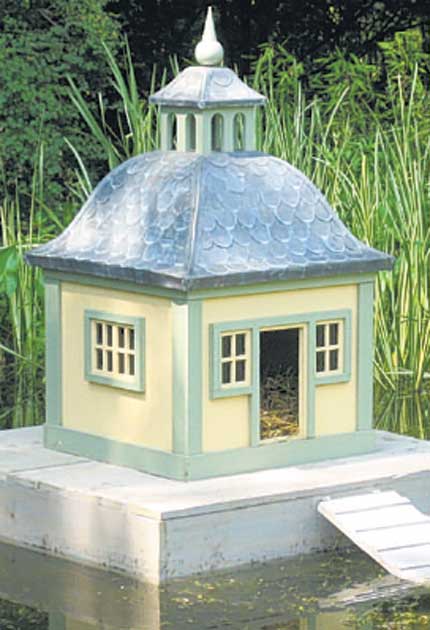

The Daily Telegraph had landed the scoop of the year: it had purchased, through a middle man, a disc containing everything claimed under the second homes allowances by all 646 MPs over four years. It was due to be published later in the year, in censored form, by the Commons. But The Daily Telegraph had got hold of the full, unadulterated version. The paper had a daily dose of stories about claims for moat cleaning, manure and mole-catching – not to mention the most graphic images of the saga, the duck island and the porn film ordered by Jacqui Smith's husband. It wasn't all on a plate, many stories needed digging out, such as establishing "flipping" by MPs – switching their first and second homes to maximise their claims – in some cases avoiding capital gains tax.

Brown's anger also reflected a legitimate criticism that the Tory-supporting Telegraph's coverage was slanted against Labour and softer on the Tories. David Cameron's claim for clearing wisteria (he later paid back the £680) was relegated to an inside page; he got off lightly despite appearing to play the system to maximise his claims for mortgage interest.

The Prime Minister was slower to "get" the scale of the crisis than both Cameron and Nick Clegg, whose party was the least damaged of the big three by specific disclosures. Eventually, Brown realised that MPs could no longer regulate themselves and that independent oversight was needed. He rushed out his own proposals, pre-judging an inquiry he had set up into the expenses system by the Committee on Standards in Public Life, chaired by Sir Christopher Kelly.

Some of Brown's proposals – such as a daily "signing on" allowance – bombed, partly because he had not consulted his MPs or other parties first. He had the right ideas, but made a hash of implementing them – a symbol, perhaps, of his premiership as a whole. His frenetic activity created tension with Harriet Harman, formally responsible for expenses as Commons Leader. It also produced a hostage to fortune: an independent audit of all MPs' claims going back five years by Sir Thomas Legg, a retired Whitehall mandarin. He appeared to exceed his remit by imposing retrospective limits for gardening and cleaning, angering many MPs when they received his demands for backdated payments running to tens of thousands of pounds.

Sir Christopher's report brought little comfort to those MPs who believe the cure was disproportionate to the disease. Many felt that he didn't understand the need for MPs to be in two places – a constituency and Parliament. Some of his proposals – such as forcing MPs to rent modest London properties rather than helping them to buy – may deter women with young children from entering politics, hardly a forward-looking move. His remit excluded MPs' pay, so his proposed squeeze on allowances raised fears that Britain might return to the days when only the well-off could afford to enter Parliament. As with Sir Thomas, party leaders and most MPs felt they had to swallow the medicine, however bitter it tasted.

There was another side to the story, but it was drowned out by the magnitude of the scandal. The fact that most claims were within the rules was irrelevant to a public bound to recoil with horror at the few rotten apples and assume the rest were just as bad. The Commons culture of encouraging new boys to obey club rules and claim their allowances also failed in the court of public opinion. At times the media went over the top, without pausing to wonder whether the endless disclosures were damaging the entire political system. But the story was just too good to ignore.

Whenever the fire died down, it soon burst into life again. There were suspicions that, while signing up to sweeping reforms in public, an old Westminster guard was secretly working to stifle them. Meanwhile, Sir Ian Kennedy, chairman of a new Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority, made clear he would not be bound by the Kelly proposals, even though they had been accepted by all parties. There were more damaging headlines when MPs won a right to appeal against the Legg recommendations, again sending a confusing signal to the voters.

After another lull came the publication this month of MPs' claims for 2008-09, with fewer blanked out than in June, when the Commons authorities invited ridicule by issuing hundreds of pages of black ink. To the duck island was added another image of the year: a bell tower. And yet perhaps the latest torrent had less impact than the initial burst in the spring. The damage had already been done.

The saga is not over. Brown had hoped to have written the last chapter by July, but there is still unfinished business. Sir Thomas's final verdict on how much individual MPs must pay back will not be known until the new year, with several disputing his findings.

The expenses affair will certainly be a big factor at the election. MPs report continuing hostility on the doorsteps – if, that is, people are prepared to even open the door to them. They have become used to cynical jibes about receipts when they shop in their constituencies. Some MPs, and spouses, have faced abuse or threats.

A clutch of independent candidates may not win seats, but they could still help to turf out a sitting MP by allowing others in. There will be local campaigns against high-profile "offenders" including the former Cabinet minister Hazel Blears, fighting for her political life in her native Salford. Some MPs whose own claims did not make waves could fall victim to the general ill will towards politicians.

Although the claims for a moat and a duck island revived images of a Conservative Party that Cameron hoped he had buried, Labour will almost certainly take the biggest hit. It will be defending most seats next year, its MPs vulnerable to attacks by insurgents armed with their damaging receipts.

The governing party is always likely to take the biggest share of the blame for such a crisis. A new Parliament and new government may not cure the body politic but may be seen as part of the healing process. Most ominously for Labour, the expenses scandal may add to a "time for a change" tide already threatening to sweep the party away after 13 years in power.

The things they claimed for: Chandeliers, chocolate bars and bath plugs

"No expenses were spared" as "snout-of-order" MPs in the "House of Frauds" found themselves on the "swindler's list". It was, in short, a "flipping outrage".

But the expenses scandal did more than test the wits of headline writers. Among the more trivial bombshells to rock the political establishment was the revelation that Kenneth Clarke is rubbish with computers. The shadow business secretary and MP for Rushcliffe claimed for a copy of 'Windows XP for Dummies' (RRP £16.99).

Computer literacy was no concern for Sir Michael Spicer, who was more interested in illuminating his manor house. He claimed £620 to fit a chandelier (the light he bought himself). The garden needed work, too; one's hedge, surrounding one's helipad, will not trim itself (cost: £609. The "helipad", it should be added, was in fact an area of stone with an ironic nickname – a "family joke", Spicer said).

Gardens also engaged the energies of Patrick McLoughlin (£158.63 to remove a wasps' nest), Alan Duncan (£598 to overhaul his ride-on lawnmower), Margaret Beckett (£600 for hanging baskets), and Christopher Fraser (more than £1,800 for cherry, laurel and red-cedar trees).

Former home secretary Jacqui Smith watched her Cabinet career drain away after (or perhaps in spite of) claiming 88p for a new bathplug. John Prescott found himself in double trouble – not just Two Jags, but Two Loo Seats, too. Mr Prescott insists that he did not buy two new toilet seats but claimed for a plumber to tighten them after repairs were carried to his toilet.

Austin Mitchell took the biscuit by claiming 67p for a packet of Ginger Crinkles (that and £1,296 for bespoke shutters at his second home). Alan Duncan likes a mint imperial, a packet of which made up part of a £19.55 tea-and-snacks claim, while Sian James couldn't be without a 59p chocolate Father Christmas. The millionaire David Cameron also charged for chocolate, in a claim for his staff that included a Galaxy and a Mint Aero.

As the dust settled on the furore – the integrity of Parliament had not endured such damage since the Blitz, according to the new Speaker, John Bercow – two figures emerged to epitomise all that seemed rotten in the House. Douglas Hogg's parliamentary career got stuck in the mud when he stepped down after repaying the £2,115 he apparently claimed to have his moat cleaned. A similar fate befell Sir Peter Viggers, who announced his retirement after his £1,645 duck island, inspired by an 18th-century Swedish house with hand-cut roof tiles, became a national joke.

Viggers wasn't the only victim of the scandal; the house's designer, Ivor Ingall, who has also created a chicken house in the form of a Scottish castle and a Parthenon-inspired bird table, said in a radio interview that "people are not ordering the garden follies that I produce quite like they were." Simon Usborne

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks