DJ Taylor: To clean a house, you start at the top

Dominique Strauss-Kahn's travails show we no longer apply different moral standards to those with power

No Briton in hot pursuit of Gallic licentiousness can have failed to be amused by the latest revelations in l'affaire Dominique Strauss-Kahn. M Strauss-Kahn, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, has spent the week being interrogated over his alleged participation in orgies with prostitutes in Lille, Brussels, Paris and Washington. He has admitted to attending the orgies, but denies any part in their organisation. Not the least spirited of the many interventions on either side has come from his lawyer, Henri Leclerc, who remarked that his client could not have known if a particular young woman to whom he had been introduced was a prostitute as she was not wearing any clothes.

Deplorable as all this no doubt is, it raises a question that has hung over most forms of public life for at least half a century. How is that those serial misbehavers, those drunks and fornicators and trust-abusers elevated to high office by a grateful establishment, got away with their misdemeanours for so long? To read Peter Paterson's life of the former foreign secretary Lord George Brown, for example – a man who could have become prime minister in the 1960s – is to shake one's head over its subject's ability to prosper in government despite his habit of becoming "tired and emotional" at the drop of a hat.

Among other things, Paterson reveals that during the 1963 Labour Party leadership election Brown was so drunk that he had to be kept out of the House of Commons tea room for fear of disillusioning potential supporters. Much the same smokescreen turns out to have hung over one of Brown's colleagues in the Wilson cabinet, now a decade dead, whose biography apparently remains unwritten owing to the difficulty the biographer first commissioned to write it had in dealing with all the sexual irregularity.

On the plus side, it could be said that the new spirit of vigilance that attends M Strauss-Kahn's embarrassments has been working its way up from the world of everyday life for some time, and that certain kinds of behaviour that would have been put up with 30 years ago are now beyond the pale. I can remember, back in the 1970s, hearing my parents discussing whether a member of the church choir would be safe from some old roué known for his attentions to "the ladies" and thinking, even then, that any choirmaster who knew his business would have barred the old goat. The symbolic significance of M Strauss-Kahn's humiliations should not be underestimated.

It was a bad week for professional sport. With the fallout from last weekend's post-WBC boxing championship punch-up continuing to descend, several Chelsea footballers dining al fresco on their hotel balcony found themselves being racially abused by the Napoli "ultras" gathered in the street below. Meanwhile the Prime Minister has hosted a summit, attended by such soccer luminaries as John Barnes and Sir Trevor Brooking, aimed at driving racism and homophobia from the game.

As a life-long fan of soccer, I always marvel at its trick of resolutely ignoring the effect that the conditions in which the game takes place is likely to have on the way it is played and watched, of imagining – to put this distinction more crudely – that the sport has some kind of moral element while all the evidence suggests that it is driven entirely by money. The Premier League is, after all, a commercial entity. Its fixtures are played out in an atmosphere of rancour, and yet there still floats above it all the old romantic clouds of "sportsmanship" and "beautiful games". The occasional collisions between these two views can be very confusing, as when a Match of the Day pundit who has just lamented one player's refusal to shake the hand of another then commends a defender for "taking one for the team" – that is, getting booked for chopping down an opponent with a clear run on goal.

Of course soccer has been having it both ways since the first paid footballer. The wonder is, in this landscape of cut-throat competition, that any human feeling survives at all. Just as I never switch off a televised boxing bout without feeling faintly surprised at the absence of fatalities, so I never attend a Premier League game without congratulating myself that a pitched battle hasn't broken out. We are rather lucky, really.

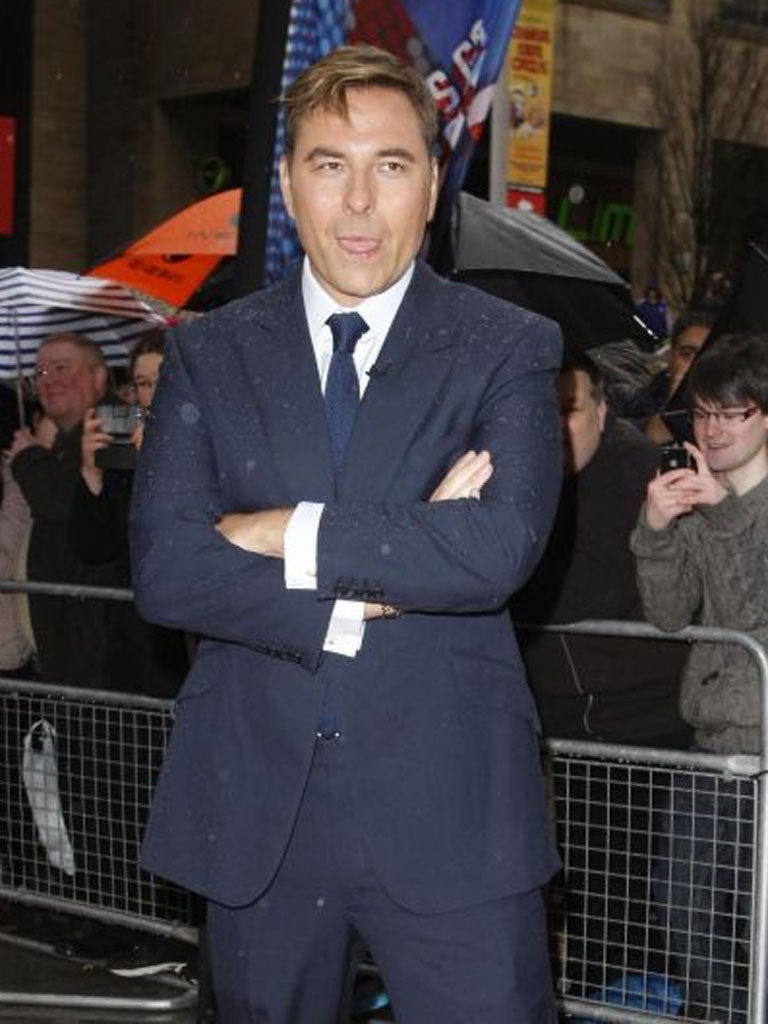

Arts world story of the week was the news that BBC1 has commissioned an adaptation of David Walliams's children's book, Mr Stink. The story, which takes in a small girl's concealment of a tramp in her garden-shed, also includes a role for "the Prime Minister", which will be filled by the author himself.

No disrespect to Mr Walliams, or the merits of his book, but this seems to me a pattern example of the modern media's habit of feeding off itself, in the same way that Fiona Bruce gets to front prime-time art documentaries or Peter Snow forsake his swingometer for an instant makeover as a TV historian. Any number of excellent children's books have been published in the past couple of years. Why not dramatise one by somebody who isn't already a television staple? This tendency reached its nadir last autumn when Frank Skinner turned up presenting a BBC4 documentary about George Formby. Mr Skinner's enthusiasm for his hero couldn't be faulted, but one could have done with a bit less of the presenter practising his ukulele and rather more of the actual subject.

The most interesting book published last week was Tim Moore's You Are Awful (But I Like You), reviewed on page 69, billed as a study of "unloved England". The guide to where not to go has been done before – Mark Lawson once produced an anti-gazetteer entitled All The Worst Places – but Mr Moore's tour of such benighted locales as Leysdown-on-Sea and Doncaster has an engaging sharpness.

Among the godforsaken extremities in which he fetched up, I wasn't surprised to find Great Yarmouth, here stigmatised as "the end of the world". Mr Moore is right, of course. Indeed, walking along its beach last November, in sight of the gas terminals, I found myself confronted with the hugely emblematic spectacle of a dead duck. On the other hand, why pick on the place so often? (I am as guilty as Mr Moore, by the way, having written three articles lamenting Yarmouth's awfulness in the past 10 years.) The answer would seem to lie in our fascination for faded glamour. Seventy years ago, the town boasted a fishing fleet, a boat-building industry and rows of prosperous terraces. Now it has some of the worst social deprivation in southern England. If I were the local tourist board, I'd be milking the Dickens connection (see the Yarmouth chapters of David Copperfield) as a – no pun intended – last resort.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks