Donald Macintyre: If these strikes work, they'll buck a decades-long trend

Whenever national strikes have been threatened in this century, ears have been pricked to detect the distant echoes of those in the last one – especially now that there is the prospect of industrial struggle against a Conservative government.

Some Tory MPs, young enough to have been at primary school during the epic confrontation between Margaret Thatcher and Arthur Scargill's miners 27 years ago, must be asking themselves in irritation: didn't she see off all this for good?

The scale of the deficit and of the measures being adopted by the Government to tackle it mean that nothing can be predicted with certainty. From Peterloo to the poll tax riots, the resilience of the normally phlegmatic Briton has always had its limits. The territory is uncharted.

European anti-austerity strikes, such as the one called for yesterday in Greece, could catch on. But neither side should assume the unions will be the blunt instrument that forces the Government to change course.

Embedded in the Conservative psyche, of course – at least until the miners were finally defeated in 1985 – was the belief that the 1974 strike by those same miners brought down Edward Heath's government (just as Labour believed the "dirty jobs" strikes in the winter of 1978-79 removed the last remaining hopes of Jim Callaghan's re-election).

In reality, those of us who covered the big national public sector strikes of the 1970s and 80s can remember only a handful that were unequivocally successful, such as the miners in 1974 and the firemen in the long cold winter of 1977-78.

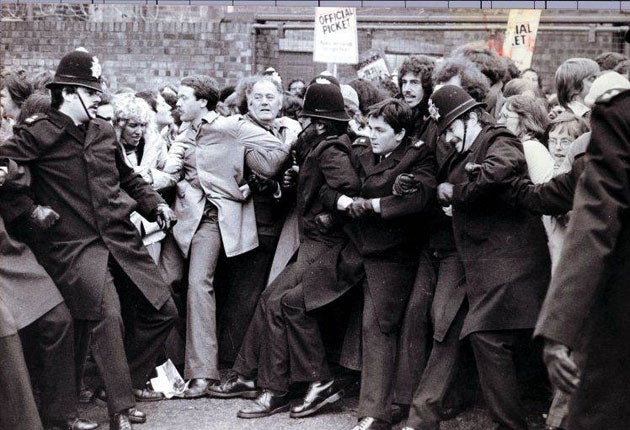

As both groups relied, in the face of real physical danger, on an unusually high degree of mutual aid and dependence in their working lives, they had no problem finding the same solidarity when on strike – whether in sometimes violent run-ins with the police, picketing in extreme weather, or facing financial hardship. Both groups had the support not only of other trade unionists but – to some extent – of the wider public.

Whether that last will be as easy to sustain among parents, patients and others hit by the stoppages now being planned by the unions in already hard-pressed services remains to be seen. One variable, of course, is the secret ballot. The miners' leaders in 1974 balloted their members and won; in 1984 they didn't, and eventually lost.

One of the paradoxes of the Thatcher legacy is that unions are now obliged by law to hold a ballot, which confers some legitimacy if there is a yes vote. If the most imminent stoppages are about preserving public service pensions intact, they may not be the most popular cause among those who don't work in the public services. If they are against job cuts, reduced services and the Government's management of the economy, can they stay the distance?

If they do, they will buck a steady trend of the last decade or more. For the strike weapon has been nowhere near as formidably or frequently unleashed as it once was, thanks to privatisation, the shift from manufacturing to services, and perhaps a recognition among trade unionists of its limitations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks