Robert Fisk: Butcher of Buchenwald in an Egyptian paradise

War criminals

Not long ago, a Hizbollah fighter in Lebanon insisted to me that there was life after death.

With my fascination for "life beyond the grave", I told him to prove it. "Mr Robert," he replied, "do you believe in justice?" Well, yes, I said, I did. "So do you think there is justice in this world?" Nope, I replied. "Well that proves it. If there's no justice in this world, there must be justice in the next – so there's another life!"

I remembered this piece of esotericism a few days ago, when in Egypt I bought a second-hand copy of an old book about the Cairo suburb of Maadi, a grand old place of villas – until it was destroyed, of course, in Cairo's 1970s building plague – in which British colonialists, Germans and Austrians and Egyptians (many of them Jewish) and Italian and Armenian families made their homes amid parties and tennis matches at the Maadi Sporting Club and the children's college and, during the Second World War, a vast horde of Commonwealth troops waiting for El Alamein.

But one page caught my eye. Samir Raafat, who must know more about Maadi than anyone else in the world, had dug up the story of a quiet German doctor, Carl Debouche, who moved into a bland house on the corner of Orabi Street in 1958. Most of the neighbours, according to Raafat, noticed that he would spend hours at his window, staring at the Maadi synagogue across the road. Then shortly afterwards, an Egyptian postman called with a parcel that exploded in his hand, blowing his eye out. "Debouche" was unharmed. Readers, however, will already have guessed what is to come.

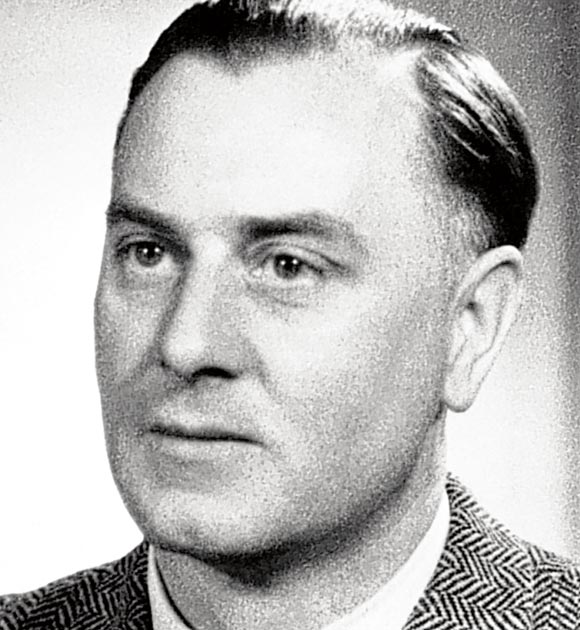

For yes, indeed, "Debouche" had a dark past. He wasn't even "Debouche". His real name was Dr Hans Eisele, former Nazi party member 3125695, former SS Hauptsturmführer (SS no 237421) and convicted war criminal.

He began by fighting on the western front and ended up working in Nazi concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Natzweiler, Dachau and Buchenwald. According to the American who prosecuted Eisele, Colonel William Denson, Eisele started off as the good doctor, called "the Angel" by prisoners, but steadily became cruel and sadistic, until, at Buchenwald, he was called "the Butcher" because he carried out medical experiments on prisoners, allowing them to die slowly after injections of cyanide.

He was twice sentenced to death (in 1945 and 1947), but both sentences were commuted until in 1952 – and this showed the degree to which the then West German government connived in helping its war criminals – he was freed from Landsberg prison. With compensation! So he set himself up as a doctor in Munich and then fled six years later when he was warned he would yet again be arrested.

So those neighbours in Maadi were right to be suspicious. And, of course, if the West Germans were grotesque in their attitude to war crimes, so was Nasser's Egypt, which positively welcomed ex-Nazi scientists and torturers to help to run socialist Egypt. Alois Brunner, the man who sent the Jews of Salonika to Auschwitz, was one of them (until he set off to help Syria's secret policemen) and he may have been one of the men and women who attended Eisele's all-German soirées. Eisele's true identity, of course, meant that he had to close his practice in Cairo and he died a widower in 1967. But he was given a friendly funeral at the German cemetery in Old Cairo.

So, mindful of my Hizbollah acquaintance's belief in the afterlife – and of the Marriott hotel's advice that in Cairo it might be easier to find a dead man than a living one – I set off this week to find the last resting place of the Butcher of Buchenwald. It took about two hours even to locate the German cemetery; with infinite irony, it lies only a few hundred yards from Cairo's oldest synagogue and a British Second World War graveyard. But sure enough, the moment I walked through the Teutonic portals, there was a little paradise of tall trees and flowered bushes and – cut off from the roar of Cairo – a peaceful garden, its concrete paths washed, its shrubbery carefully cut.

The cemetery keeper's wife, an unsmiling lady who inspected my five Egyptian pound tip as if it might be forged, produced the book of the dead. And there he was, complete with his real identity and his false name. "Eisele, Hans, Dr med. 13/3/12 – 3/5/67, Carl Debouche 1901-1957." There was no explanation for the fake name or the fake dates beside it. Eisele may have invented the first date. But why would he invent the second – before he even arrived in Cairo? Then there was that slight missing heartbeat when you glanced to the right of the page: "Grave No 99."

No movie would dare carry that cemetery number for a doctor from hell. But the grumbling Egyptian housewife walked me beneath the trees and pointed at a cement rectangle with the number "99" on a small marble plaque and, at the top, a massive piece of black stone – carved, as they say, "from the living rock" – which bore the words, crudely and perhaps in a deliberately "Aryan" way fashionable in the 1930s – "Dr Med Hans Eisele. *13/3/12 + 3.5.1967".

That's all. He got away with it. There is a pink flower and some cabbage-type plants on his well-tended grave. Far from the fumes and chaos of the city he fled to – far further than the fires of Buchenwald – tucked away at the side of this pretty little cemetery, the doctor from hell ended up in a little paradise. If my Hizbollah man's theory is right, of course, he has already been sentenced by a judge far more erudite (and a lot harsher) than US Colonel Denson. Be good to know, though, wouldn't it?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks