Philip Hensher: The objects of my affection

The week in culture

I knew this was going to be good when, quite early on, I learnt from this radio series how to pronounce "metope". For some reason, I'd always had the misapprehension that it had three syllables. And then Radio 4, satisfyingly, put me right.

Has there ever been a more exciting, more unfailingly interesting radio series than the Radio 4/British Museum venture, A History of the World in 100 Objects? It is such a beautifully simple idea, to trace human civilisations through the objects that happen to have survived. Each programme, just 15 minutes long, focuses on just one thing, quite patiently, without dawdling. At the end, you feel that you have learnt something, and learnt it with pleasure and interest.

For years to come, the BBC will be able to point to this wonderful series as an example of the things that it does best. It fulfils, to a degree that one thought hardly possible any more, the BBC's Reithian agenda of improvement and the propagation of learning and culture.

In all sorts of ways, the series goes against conventional thinking about how culture should be presented by the mass media. The objects weren't chosen by a phone-in poll, but simply decided upon by a team of people who genuinely knew what they were talking about. It is quite easy to imagine the BBC, considering this commission, deciding that each programme should consist of a "celebrity" talking about what this object meant to them – Chris Moyles talking about the Lewis chess set, Alan Titchmarsh on Mughal miniatures.

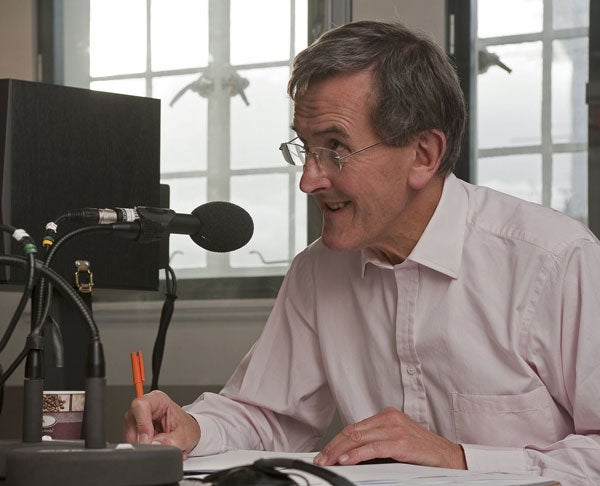

Instead, we have Neil MacGregor, a calmly enthusiastic presence, talking confidently about his subject. It goes against all conventional wisdom, and of course, it has been an enormous popular success – everyone is listening to it and talking about it, or so it seems. The CD box set of the series is surely going to be this Christmas's most popular gift, and will go on selling steadily for years to come.

What is so impressive about the series is the way it opens up that most daunting of museums, the British Museum, and turns it into a huge story. Popular as the Museum is, I wonder what first-time visitors make of it. We all have our favourite little corners of the Museum, which change from time to time – I used to love that crystal skull and the mummies when I was a boy, and now it's more the Persian stuff. I look forward to the day when I start liking the stuff that means nothing to me now – maybe even those hideous Aztec remains.

But has anyone ever managed to spread their appreciation over the whole museum simultaneously? I've always doubted it, until Mr MacGregor's wonderful series, when I start to think that he might very well do. (Not something to be taken for granted, even of the director of the British Museum). More to the point, the series shows the listener that he, too, might be able to follow the huge story from beginning to end, and appreciate the whole lot with gusto. I don't suppose it will ever happen, but the illusion is palpable.

Given the immense success of the series, you have to wonder why, after all, it wasn't on BBC television in the first place. Brilliant radio though it is, it does describe objects rather than show them. On one or two occasions, allured by the account, I, like many listeners, went and looked at a photograph of an unfamiliar object. Sometimes, through no fault of the programme, you get the wrong end of the stick, and the thing doesn't look at all as you had supposed.

We can thank heaven for small mercies. On television, we would have had to have had constant shots of presenters zooming round the world; a race against time to preserve this object or that; celebrities; phone-in votes; Mr Stephen Fry; and seven objects thrown down our gullets, indigestibly, per hour of broadcast time. On radio, we are still allowed to have 15 minutes of contemplation and thought, and not actually being able to see the object seems like a small price to pay for that.

It seems inevitable, and welcome, that the series will be remade for television, so important a statement does it seem of the BBC's best principles. Please, if it happens, it should remain as it is: 15 minutes long, Neil MacGregor talking, in a room, with the camera largely on the object under discussion. That sounds like perfect television to me, just as this has been perfect radio.

A great Dame – shame about those awful operas

The thing that none of the obituaries of Dame Joan Sutherland commented on was what a bizarre career she had. For a start, after her first years, she hardly ever appeared unless her husband, Richard Bonynge, was conducting the orchestra – I can't think of any other singer who has ever made a stipulation so consistent, however excellent Mr Bonynge's conducting was. And I know this is largely a matter of taste, but, goodness, for a singer of such greatness, she didn't half appear in some terrible operas. Even some of her most adoring fans grew to dread the Massenet Esclarmonde which Dame Joan and her husband championed – you can imagine what the musicians in the orchestra pit used to call this unforgivable load of art nouveau twaddle. Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet, Le Roi de Lahore, that appalling La Fille du Régiment – well, I believe some people like that sort of thing. Oddly enough, though, Dame Joan in her early career sang in some really good operas. Amazingly, she created the role of the heroine in The Midsummer Marriage, and as late as 1957 was still singing Eva in Die Meistersinger. Few people will think that Dame Joan had anything but a glorious career, but she falls into the category of great artists in an art which means nothing to me. What a Wagnerian she would have made! No-one can guess what a magnificent Isolde or Brunnhilde was sacrificed on the altar of endless rubbish by Massenet.

Tate sows seeds of discontent

Mr Ai Weiwei's wonderful installation at Tate Modern consists of 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds. You may walk over them, sit on them, pick them up and run them through your hands, examine a handful of them.

The thing that you may not do is pick up one or two and steal them. Mr Ai was frank about the appeal of this. If he were a visitor, he said, then of course he would want to take one or two. They are lovely little objects, after all, and the temptation is very strong. The Tate was clear about this. Visitors should not remove any of the sunflower seeds. Still, there are a hundred million of them, so if visitors did choose to pocket one or two, then it would take a while to make a noticeable dent. The Tate curators, when I asked them, said that they would "see what happens", but it wouldn't surprise me if they had a million or two sunflower seeds up their sleeves.

The work of art that is consumed by its audience is not a new thing. The boiled eggs that Piero Manzoni served up to an audience at a vernissage as a work of art were mostly eaten at the time, but I believe one or two survive, very brown and depressing objects. Interestingly, Mr Ai's intentions seem less obvious. Of course, if you do steal any of his sunflower seeds, the Tate is going to make you put them back, and probably phone for one of those aesthetic/ philosophical policeman so beloved of G K Chesterton to sort the whole puzzle out.

arts@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks