Steve Crawshaw: Two decades on, Bosnia's war crimes should haunt Europe

The culture of denial was as disturbing then as it remains now. Painful truths need to be accepted

Twenty years ago today, gunmen opened fire on a peace protest in Sarajevo. Five people died that day. There was a terrible sense of foreboding for Bosnians as the killing began. Samira, a medical student in the town of Bijeljina, told me: "We are afraid. I want to stay. But I can't be cold-blooded about it." She was right to be afraid.

During the next three years around 100,000 people died, mostly civilians. Genocide and crimes against humanity were committed once more in Europe. And, for most of that time, the world looked away.

To report from the besieged Bosnian capital, as I did for The Independent at that time, was unsettling, at best. An unexceptional European city, just a few hours from London (Heathrow to Zagreb, then hitch a lift on a UN plane to Sarajevo), was caught up in a nightmare which until then had seemed beyond all imagining.

At the city morgue, a young girl – nobody knew her name – was one of the bodies laid out on a slab. She wore a placid expression, like a waxy doll. She had been killed by a missile fired by the Bosnian Serb forces in the hills surrounding the city. The top of her head was sliced away and some of her brains were on the floor. She was still wearing her pink T-shirt and cheerfully flowery leggings, such as you could buy at Benetton; the pattern was the same as my five-year-old daughter liked to wear.

Twenty years is a long time in politics. In the centre of Sarajevo at least, the scars have been covered up. Beside the Holiday Inn – in its prime position, on Snipers' Alley – a shopping mall has opened. A plaque marks the spot where 16 people were killed by a Serb mortar shell in May 1992, while queuing for bread. Such events can seem like ancient history. Some of today's voters were, after all, hardly born when the conflict ended.

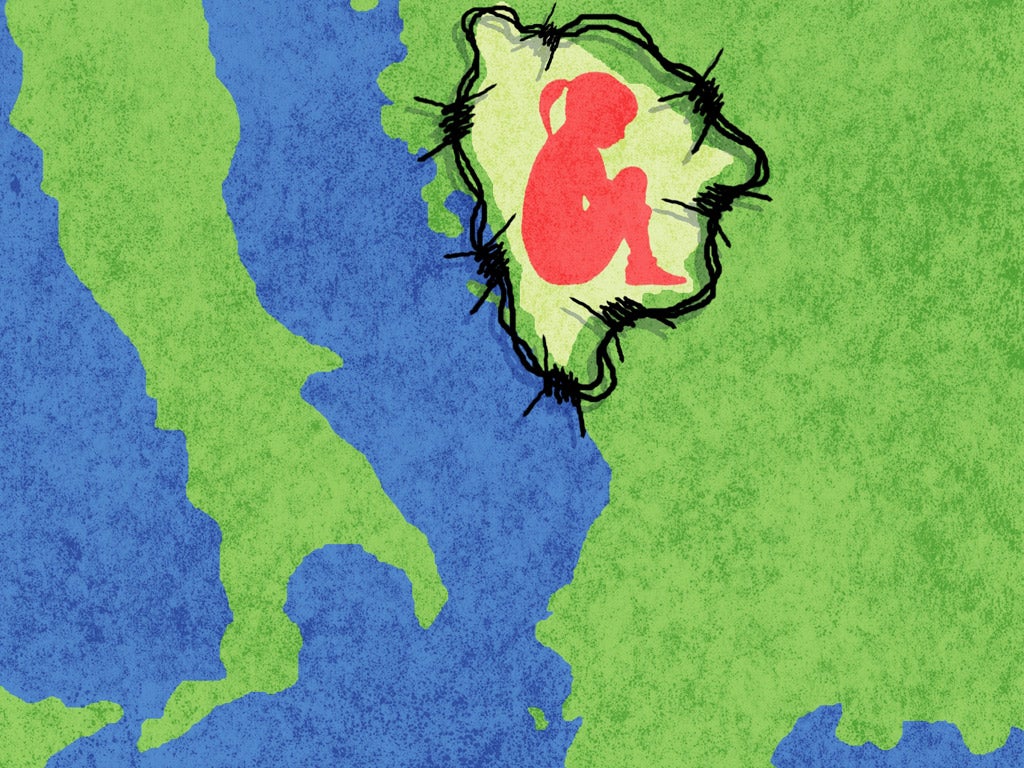

And yet, this is not history. For the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina, this is still unfinished business. A new Amnesty International report tells the story of L, who hid in the woods near Zvornik for a year. She lost her one-year-old son while fleeing Serb paramilitaries, and then her unborn child when she was tortured after her capture. She was then detained in three separate camps where was raped repeatedly. "I did survive" she says, "but only I know how."

Best estimates are that 20,000 women were terrorised by systematic rape and other forms of torture. As a direct result of the Bosnia conflict, war crimes courts, including the International Criminal Court, now recognise rape as a crime against humanity. And yet the great majority of victims have received neither reparation nor justice. In the words of one woman, "What was I guilty of when I was only 14 years old? What did I do to anybody?... All of this, I will never forget."

The understanding of the need to address the issues of rape and conflict has recently received a boost in a surprising context. The recent Sarajevo premiere of Angelina Jolie's new film, In the Land of Blood and Honey, set during the Bosnian war, brought with it a shower of headlines about "controversy". There were protests, complaints, even death threats. When the words "controversy", "Hollywood movie" and "historical record" are put together in a single sentence, we usually know what to expect – producers' dismaying disregard for the truth. In the case of Blood and Honey, however, the problem is not too little truth, but too much – about rape as a weapon of war, the brutal reality of ethnic cleansing, and civilians gunned down for daring to step outside their homes.

Complacent politicians in Britain and around the world looked the other way. But, as one of the characters in the film remarks: "It's murder for political gain. But it's still murder." After three years of the nightmare, the killing of 8,000 men and boys under the noses of UN forces at Srebrenica in 1995 proved a turning point. International pressure increased; within months, the war was over.

Apart from the fact that the guns had fallen silent, there were other reasons to rejoice in the years to come. Slobodan Milosevic, the Serb leader in Belgrade, and Radovan Karadzic, leader of the Bosnian Serbs who wanted to destroy a single Bosnian entity, were confident that nobody would ever be brought to account for the rape camps and the other crimes committed.

When I sat with Milosevic for The Independent in August 1992 – I was just back from Sarajevo, he was attending a conference in London – I asked about bringing people to account. A marvellous idea, he said. Would he find himself in the dock one day? Milosevic feigned astonishment: "Me? I am for peace!" Bizarrely, politicians believed him.

Justice did indeed seem unthinkable at that time. Nine years later, however, Milosevic was delivered up to The Hague. Karadzic, too, insisted: "We don't have snipers. Only they [the defenders of Sarajevo] have snipers." He also told me that "Albanian mercenaries" were the only people who died in the Bijeljina massacre of April 1992. It was as though he was laughing at the world. Like Milosevic before him, Karadzic is now on trial, charged with crimes against humanity and genocide. Local organisations like the Balkans Investigative Reporting Network now highlight the importance of justice for achieving a more stable society. In the words of Gordana Igric, executive director of BIRN: "The truth is important especially for a new generation, growing up believing they are victimised. And it's important for the victims, too."

But the varying receptions for Jolie's film in recent weeks have revealed the polarisation that remains. In Sarajevo, 5,000 people attended a special screening of the film in a packed Zetra Stadium. They gave Jolie a standing ovation. In the Serb capital, Belgrade, just a dozen people were reported to have attended the film's opening. In the words of one Serb headline, the showing of the film was "a fiasco". Well, yes and no. It is a fiasco only if one remains in denial about what happened.

Rape, and its use to dehumanise, lies at the heart of Jolie's shocking film. There is nothing fictional about this. Serbs did not have a monopoly on the crimes of the Balkan wars, including rape. Nonetheless, the culture of denial was as disturbing then as it remains today. For a true reckoning with the past, painful truths will need to be more widely accepted than they have been so far. The war's victims, many of whom have never been recognised, have a right to acknowledgement, justice and reparation.

Steve Crawshaw is Director of the Office of the Secretary-General at Amnesty International. He was a foreign correspondent on the staff of 'The Independent'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks