Steve Richards: The man who should speak remains silent

Gordon Brown is the convenient scapegoat, the chosen villain of the entire media and political class

There is a strange, ghostly silence in the otherwise noisy debate about the current economic crisis. Everyone, it seems, has a view – except the only other public figure to have been at the heart of a similar emergency in 2008. Gordon Brown, who struggled to find a compelling and authentic voice when in power, now has no voice at all.

Or at least he is silent in the UK. Like other former prime ministers, he finds an audience abroad. This country has a pattern in its treatment of former prime ministers, one that says as much about us as it does about them. When leaders depart from office, there is an exaggerated level of contempt, bordering on hatred, that makes other countries more tempting destinations.

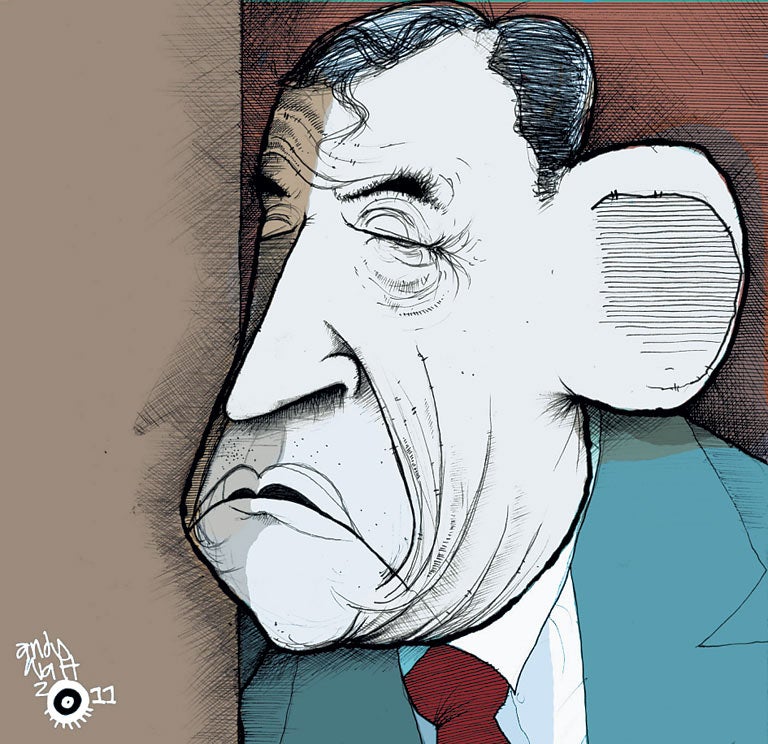

Tony Blair could not even launch his memoirs in the UK because of the anger he generates. Margaret Thatcher preferred to speak, like Mr Blair and Mr Brown, in the United States where a hero's welcome awaited. John Major headed for The Oval cricket ground the day he resigned, and for years rarely spoke in public in the UK. On leaving office, all the former prime ministers, and they could not be more different, were widely regarded as sleazy criminals, wildly incompetent or mad, sometimes all three. Lazy caricature is so much easier for us to cope with, even if it raises the collective blood pressure.

But in Mr Brown's case this pattern has reached a new extreme. At least the others wrote their memoirs to put their case. They had allies, passionate supporters who continued, and continue, to argue that they were the closest it is possible to get to greatness. In the case of Lady Thatcher, new levels of deification will soon be reached when Meryl Streep portrays her on film. All of them intervene occasionally – or, in Lady Thatcher's case, used to intervene – in matters of overwhelming public interest. Mr Brown chooses not to make his case and has virtually no one willing to do so on his behalf.

Indeed, there is a Shakespearean twist to his post-Downing Street fate. A once mighty Chancellor, feared by internal and external opponents, is now almost bullied into silence. It is in no one's interest to let him speak. David Cameron and George Osborne have a dream political narrative in which they insist at every available opportunity that they are acting only to clear up the mess left by Mr Brown. His absence, with its implication of evasive guilt, supports their simplistic account. They do not want light shone on a more nuanced version of events.

The Liberal Democrats have staked all on supporting Osborne's economic policies, and therefore seek to blame Mr Brown, too. They are joined by the Blairites in the Labour Party and in the media, who will never forgive him for his behaviour towards their hero. Former ministers know that they can get a good serialisation deal by highlighting his wild outbursts, while hiding in their largely unread texts the subtler story of what happened. The two Eds, Balls and Miliband, once Mr Brown's closest allies, know that only distance now can give them a chance to flourish, and that any association would damn them. They welcome the silence, too, and hope they can stand apart from perceptions of the past that they fear they cannot change.

As a result, only one side of a story is heard, that it is all Mr Brown's fault that Britain is now on the edge of a cliff. He is the convenient scapegoat for anyone with ambition in British politics, the chosen villain of virtually the entire media and political class. This weird coalition is damaging not only to Mr Brown, but also to the rest of us trying to make sense of what is going on. The origins of the current crisis are multi-layered. Some of the layers, are missing.

Most immediately, a case can be made beyond vacuous guesswork that Mr Brown would have tried to make more of last week's EU summit, a puny gathering that was supposed to have saved the euro and instead produced a weak agreement within the eurozone and some posturing from David Cameron. Neither the agreement nor the posturing will get anyone very far.

In the light of what has happened since, Mr Brown's diplomatic hyperactivity from the autumn of 2008 into the spring of 2009 seems more successful than it did at the time, persuading extremely cautious leaders to implement a fiscal stimulus in their countries and preventing several banks from collapsing. How quickly some of the leaders reverted to type and wrapped themselves in the comfort blanket of premature austerity and inactivity in relation to the banks. For a time, however, a co-ordinated international stimulus suggested that, partly because of Mr Brown's unyielding pressure, leaders were learning the lessons of the 1930s.

Re-capitalising banks, working with the relevant central bank – whether the ECB or the Bank of England – and the art of reassuring markets that what is done is done robustly are not issues most of us have to deal with in our daily lives. European leaders gathered last week and blew it. Erratically, and by no means flawlessly, Gordon Brown became an expert in all three fields. The global economy escaped depression after 2008, and most of the major economies that had become vulnerable were starting to grow again by the spring of 2010.

In the UK, borrowing levels were slightly lower than expected, and a recession that could have lasted much longer given this country's extreme dependence on the financial sector came to a relatively quick end. This is a rather more impressive sequence compared with the current nightmare in which no one seems capable of addressing the eurozone crisis and the UK totters on the edge of a second recession.

A colleague of Mr Brown tells me he is wary of re-engaging in the UK because he fears all he will be asked about is whether he throws telephones across a room. But if he does not speak out himself, no one will do it on his behalf.

Labour is failing to make more of a mark for several deep reasons. One is that it is held solely responsible for the current crisis, just as it was blamed for the so called "winter of discontent" in the late 1970s and was still being blamed for it when it lost in 1992. The past is an important part of the present in politics. If a leading player from that distant land is conspicuously silent, his or her successors can lose the arguments raging in the present. Important parts of the story can be lost and, in this frightening, complex crisis, we need to know everything there is to know.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks