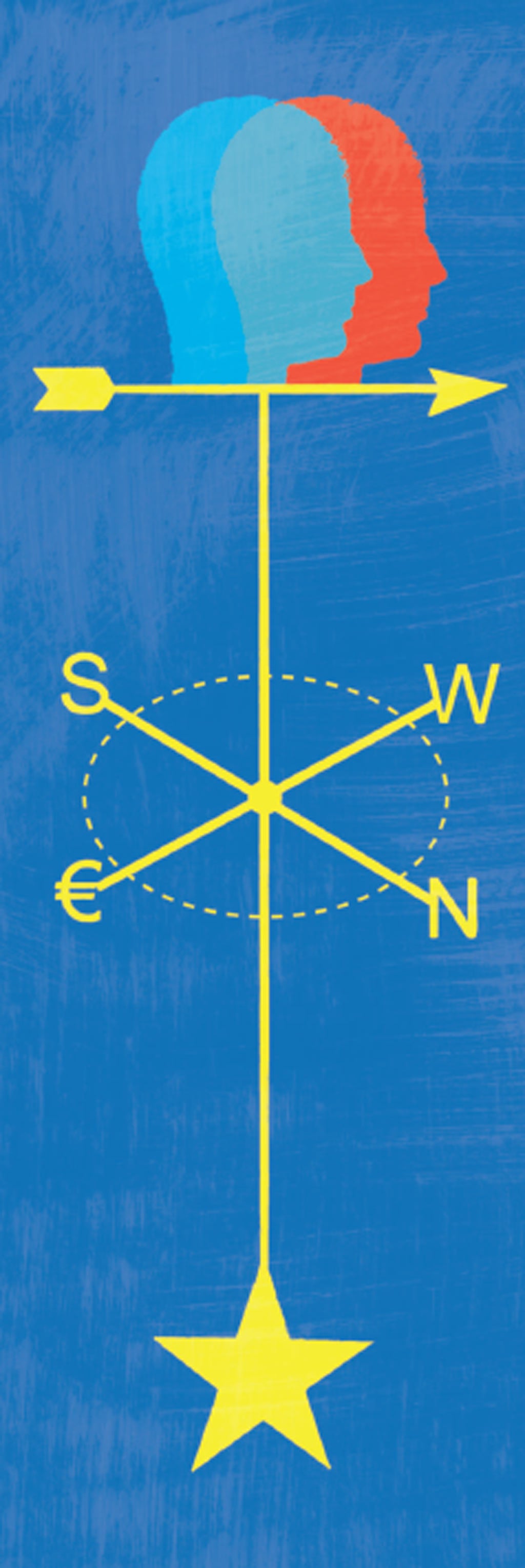

Steve Richards: Tory or Labour, the time for speaking up for Europe has gone

Both sides now accept that any transfer of powers will require a referendum

Two Prime Ministers fall; one in Italy, the other in Greece. Several leaders totter. Less dramatically, but potentially as significant, there is movement in the UK, too. The crisis in Europe brings the leaderships of the two bigger parties closer in their approach to the issue. Indeed, for all the huffing and puffing that marks every political exchange about Europe, there is, for the first time in decades, something of a political consensus in Britain.

I do not suggest that the new consensus extends to lofty insights as to how the current crisis is solved. Part of the crisis stems from the fact that no leader in Europe knows how the emergency can be resolved. But beyond the immediate calamity, and aside also from important stylistic and tactical differences, Messrs Cameron, Osborne, Hague, Miliband, Balls and Alexander dance to similar tunes, or at least they are not on different sides of the dance floor any longer.

Both sides now accept that any transfer of powers from the UK to the EU in the future will require a referendum. This is a legal requirement under recent legislation and Labour will not attempt to change the obligation if in power. In addition, Labour's leadership does not rule out an "in or out" referendum at some point. Such common ground over the thorny issue of referendums makes it unlikely that any future British government would be able to sign up to further integration of any sort. The integrationists' argument was unwinnable when Europe appeared to be booming and Tony Bair walked on water in the early years of his premiership. The current circumstances are not exactly more propitious.

In a subtly constructed speech yesterday, Labour's shadow Foreign Affairs spokesman, Douglas Alexander, warned with good cause that the repatriation of powers from the EU to Britain should not be an immediate priority. This is an important tactical difference with David Cameron, who is in danger of promising his recalcitrant MPs a transfer of powers that he cannot deliver, alienating Germany and France as he does so.

But in the same speech, Alexander stressed that "the present balance of powers can be considered" once the crisis has passed. This gives Labour the space to support or instigate such a re-balancing as some Conservatives seek prematurely. The distinctiveness is one of timing. Alexander stressed that his immediate priority is to safeguard the rights of non-euro members in any forthcoming Treaty negotiations, a view that confirms he works on the assumption, like Cameron, that the UK will be outside the euro in the long term.

This is not surprising given the current state of the eurozone, but the scale of the leap is considerable. Not so long ago, Tony Blair described his "historic objective" as ending Britain's "ambiguous" relationship with Europe; code for joining the euro. Although committed to a referendum on the single currency, Labour was desperate to avoid plebiscites on Treaties, not least because they knew they would be unwinnable. On the other side, under William Hague in particular, the Tory leadership was loudly Eurosceptic. Now we have two party leaderships who adopt a mildly expressed pragmatism.

The other key differences between Labour and the Conservative leadership as highlighted in Alexander's speech are marked, but stylistic. Referring to the Conservatives' provocative diplomacy, Alexander conveyed the sensitivity of a modern pro-European: "Constant talk of vetoes, a tendency to empty-chair those meetings that seem to be on the periphery of our interest only to force ourselves back in – these are strategic choices but they aren't very good ones."

The point is well made but it is not entirely clear whether, if a Labour government made sure the chairs were politely occupied, its objectives would be significantly different to Cameron's in terms of Britain's broader role within the EU. Alexander correctly identifies more common ground with the Liberal Democrats in the sense that Nick Clegg and Danny Alexander agree on the tactical ineptitude of seeking repatriation as Merkel and co move to shore up the euro. The trio openly describe themselves as pro-Europeans as do the two Eds.

Cameron's self-description is "Euro-sceptic". But again in his speeches Clegg stresses that he is in favour of reforms within the EU and has ruled out membership of the euro under his leadership. Perhaps the leadership of the Lib Dems is part of the new pragmatic consensus, too.

The reasons for the consensual pragmatism are straightforward, but the consequences are not. The Conservatives have lost every election in which they have played up their Euroscepticism. Cameron would like to win one. Like Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the Tory leadership still wish to be part of the European Union, at least for now. In government, Cameron and William Hague know they must work with other European leaders and be seen doing so. Their scepticism, while deep, is less ostentatious than it was.

On the Labour side, although there are differences on Europe between the two Eds and Douglas Alexander, when they worked closely with Gordon Brown they did not share Blair's erratic but at times determined commitment to the euro and the EU, regarding the Blairite passion as a convenient alternative to more orthodox ideological conviction. Now they are in charge, they leave the romanticism of "Europe" behind fairly effortlessly.

The consequences are unpredictable because at the moment anything could happen. In the short term, the army of Eurosceptics on Cameron's benches demand more than he can deliver. It is still possible, though unlikely, that the issue will fatally undermine his leadership or split the Coalition. In the longer term, a smaller eurozone centred on Germany, with an economy already growing faster than the UK's, could make puny Britain start to feel even more vulnerable. Perhaps membership will become suddenly attractive here. Who knows? The bigger two parties take an ideologically flexible approach to Europe with both being pro and anti at different points. The problem is that, during the phase they hold one view, they tend to be utterly inflexible until they switch to the other.

All that can be discerned through the fog is that as Europe faces its crisis, Britain's approach takes another unexpected turn. The leaderships of the two parties, and perhaps of all three, almost agree with each other on an issue that has torn apart British politics for four decades.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks