The government’s plan to reopen schools needs to account for a second wave of coronavirus

Editorial: The time may come when another cohort of pupils is faced with massive disruption to their lives as well as their life chances

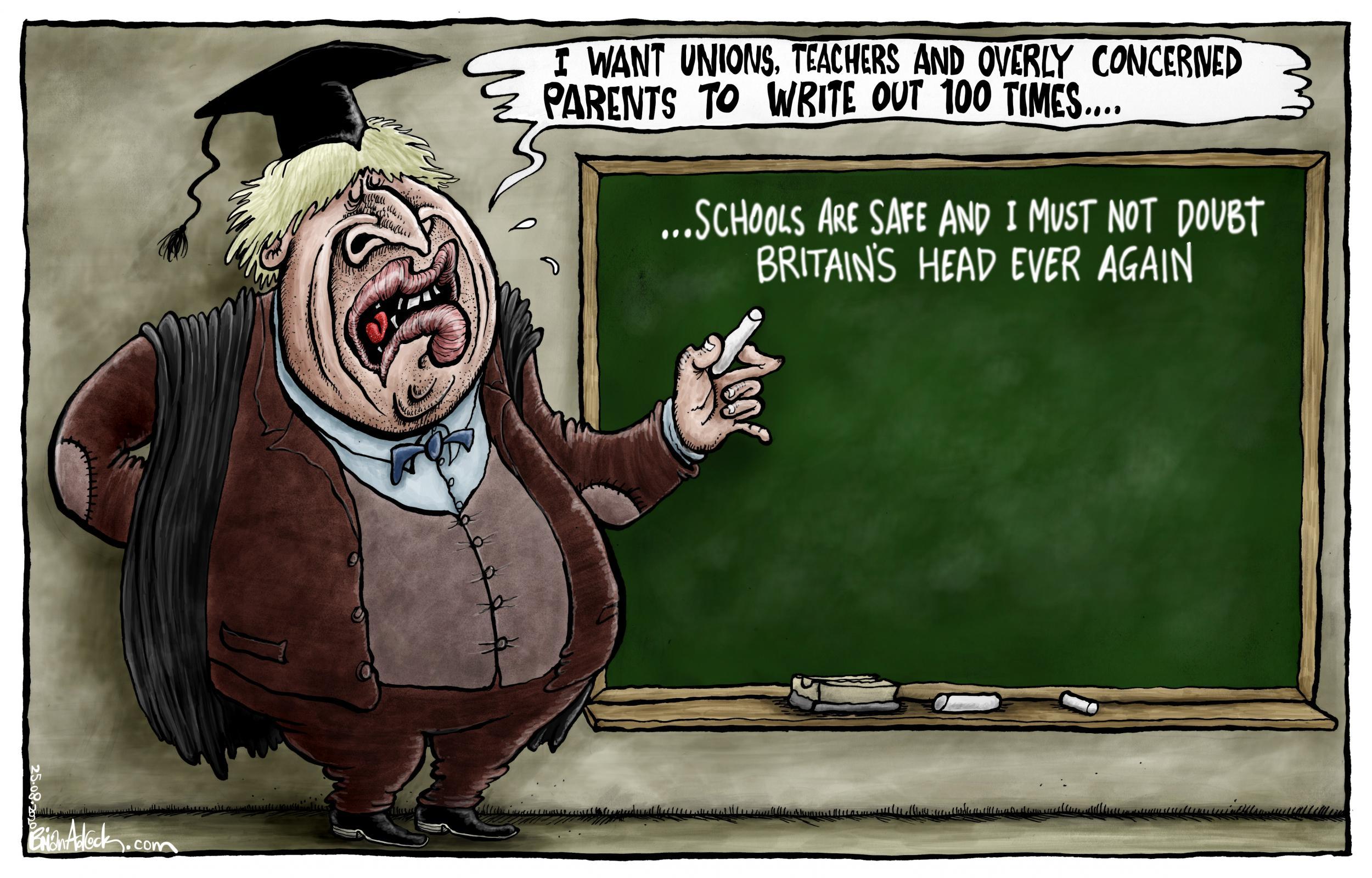

Emerging from his recent seclusion, which lasted, conveniently enough, for virtually the entire period of the exam results fiasco, the prime minister announces that it is “vitally important” that children get back to the classrooms.

He is right about that, and fortunate too that parents do not have to rely on his word alone to steer their decisions. The chief medical officers across the UK have advised a return to something like normality in education, and families in England have the additional reassuring precedent of the restoration of conventional schooling in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and an earlier experiment in opening up in Wales in June and July.

That much, then, is clear. With various precautionary measures such as “year group bubbles”, masks (in Scotland for the over 12s) and social distancing, the schools are returning to normal, in a broadly safe environment and with the necessary support of most school staff. With luck or, rather, a display of official competence hitherto lacking, there ought not to be a repeat of this year’s abandonment of exams and all that followed from that.

Yet many questions remain. Some surround the immediate risks of school infection, more adult to adult than child to adult, with reassurances needed for teachers and other staff in more vulnerable conditions. It seems the coffee break in the staff room may be a more dangerous environment than the classroom or the playing field. Will nervous parents really face fines if they cannot in conscience allow their child to attend school? Nick Gibb, the emollient and (relatively) candid schools minister, gives the impression there won’t be any unpleasantness, but push may yet come to shove for some.

There are also challenges where it would be helpful for schools to hear more precise and science-based advice. Thus, if there’s a coronavirus outbreak in a school – defined as two cases within a fortnight – why is only the year group rather than the whole school asked to stay at home? What if social distancing and the bubbles prove ineffective among gangs of gregarious infants? What support will there be for hard-pressed parents forced to take time off work in such circumstances? Where are the resources for schools to teach their students remotely at home?

More broadly, what will happen to schools if there is a second wave of Covid-19 on a national scale? That is hardly impossible, given the global trend, and the concern must be that schools will be pushed into the same sort of painful dilemmas and sacrifices that were witnessed during the first wave.

All the signs are that, this time around, the schools will be among the last places to shut rather than the first, which will at least help underpin the lives of working parents and the economy. Yet the time may come when another cohort of pupils is faced with massive disruption to their lives, their exams and their life chances.

It would be at least something to know that the mistakes made during the great algorithm scandal have been acknowledged and fixed, if there is to be a next time. Given that Chris Whitty, the chief medical adviser to the UK government, cautions that a vaccine is about nine months away, another lost year certainly cannot be ruled out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks