Osborne drops his deficit commitment, but there is still a long way to go

Whoever assumes the Conservative leadership and becomes the next occupant of 10 Downing Street will have to face the most challenging task since 2008

Rather shamefully, and with few exceptions, the political and economic establishment had little in the way of a contingency plan if Britain voted to leave the European Union. That has not helped matters in these past few momentous days, but there was always going to be something approaching chaos after a Leave vote. So we should be thankful that, at last, we are glimpsing the outlines of how our leaders believe we can make our way through what the Prime Minster, in that understated way of his, described as the “choppy waters” ahead.

Only the Bank of England seems willing to tell it like it is and to act boldly and decisively to steady nerves and provide reassurance. By offering £250bn the Governor, Mark Carney, and his colleagues have ensured that no such intervention would be required. The effectiveness of a swift “shock and awe” approach was a lesson learned in the banking crisis, and just as well.

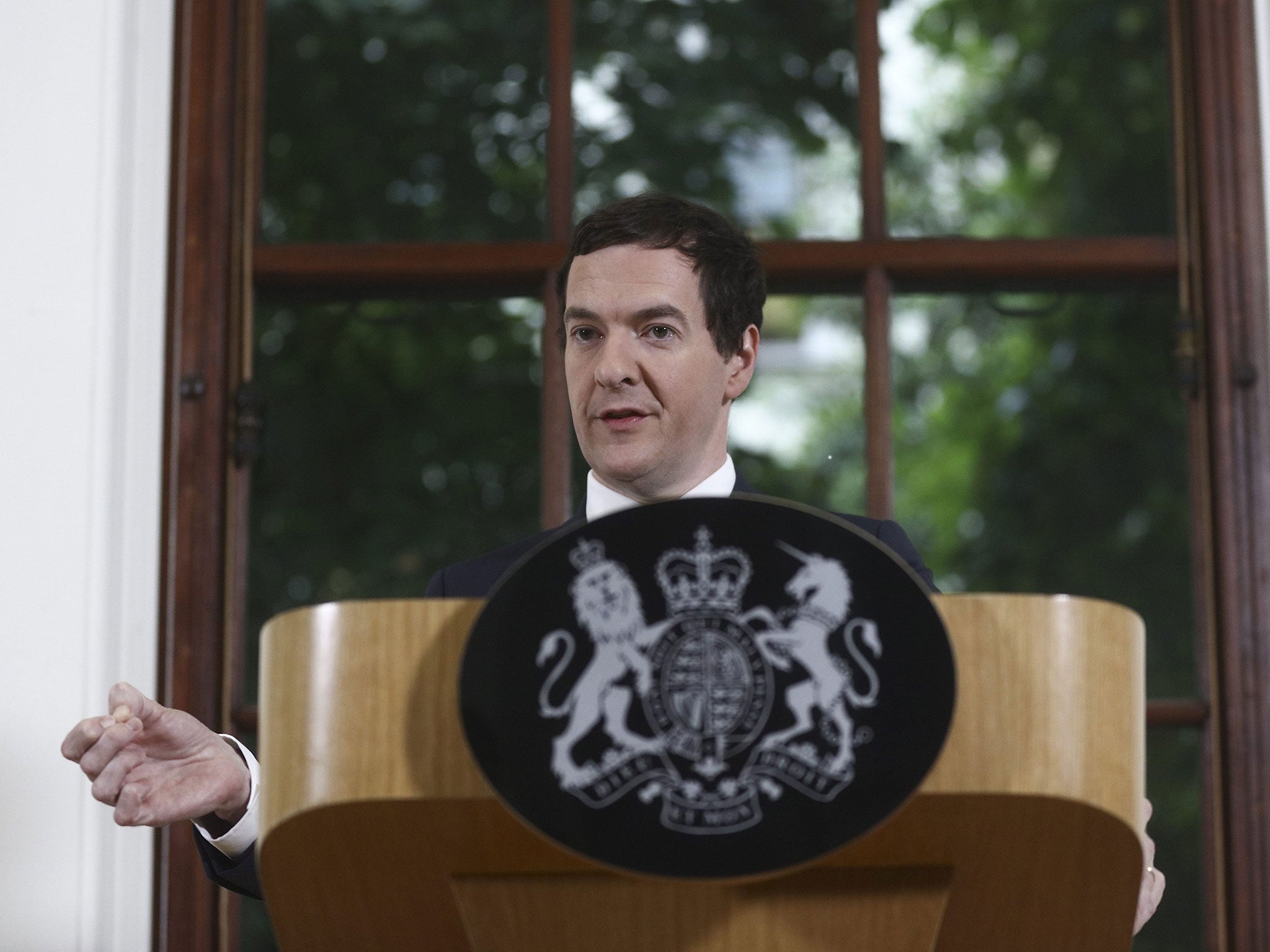

Chancellor George Osborne has certainly done the right thing in abandoning his commitment to achieve a Budget surplus by 2020. In reality, as with so many of the Chancellor’s economic targets since 2010, that may have been an over-ambitious aim in any case, but it seems both entirely unrealistic and counterproductive to pursue this arbitrary goal in the current circumstances.

The skill in economic management is to take decisions that are contingent on what is happening in the “real economy”. Nowhere can this be more obviously the case with Brexit and the negative economic shock it will inflict on the British economy in the coming months and years. Whatever the longer-term advantages of leaving the EU – and they remain far from clear or compelling – there is inevitably going to be dislocation and disruption and uncertainty in the short to medium term. That, as was signalled by the Remain campaign, will hit living standards, property values, savings, jobs and public services in the run-up to the 2020 general election.

Whoever assumes the Conservative leadership and becomes the next occupant of 10 Downing Street will have to face the most challenging task since the financial crisis in 2008.

It was startling to hear Michael Gove in his leadership campaign launch declare that, as the candidate “for change”, he wanted to force the pace of reform across the domestic economy at the same time as dealing with the consequences of Brexit. Mr Gove, not hitherto noted for any great passion for economics, was perhaps laying some claim to the chancellorship in the event of one of his rivals winning when he spent so much time on detailed proposals for economic and industrial policy. He was certainly right to lay out an ambition to build hundreds of thousands of homes a year, both for private ownership and social rent – but, apart from pledging £100m for the NHS from the (much exaggerated) money we will save on our EU net payments, it was not obviously clear where Mr Gove would find the funds for his projects in a Britain with zero growth or indeed in recession caused directly by Brexit.

The job of a prime minister may well be to lift the morale of the nation and tell us all why Britain is the best country in the world; but as more and more companies declare their intention to move their headquarters, such as easyJet, or shift operations or investments over to the continuing EU’s single market, the successor to David Cameron may also have to issue some Churchillian warnings about the sacrifices that may have to be endured well before the sunlight uplands are reached.

Mr Gove made clear that he would not activate Article 50 “this calendar year”, and not until he had conducted “extensive” preliminary conversations with our friends in Europe. We would, he added, be activating Article 50 – the formal procedure to leave the EU – “in our own good time”. That may be easier said than done. He is right that the British Government retains its legal initiative in this; but he is wrong to assume that European officials and minsters will be willing to engage in such “informal” talks. Mr Gove was probably too busy to catch BBC’s Newsnight, but he will have heard about the comments made by Cecilia Malmstrom, the EU trade commissioner. She put the EU side of things quite bluntly: “First you exit, then you negotiate.” Different commissioners and minsters have made markedly different noises in recent days, and one can only hope that the charm and diplomatic skills of the next prime minister will be sufficient to induce them into a good deal for Britain. The signs are not encouraging.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks