Harriet Tubman was bought and sold as currency. Putting her face on a banknote is an affront to her memory

Tubman and the slaves she helped to free struggled against the notion that they were no more than assets to be used by racial capitalism

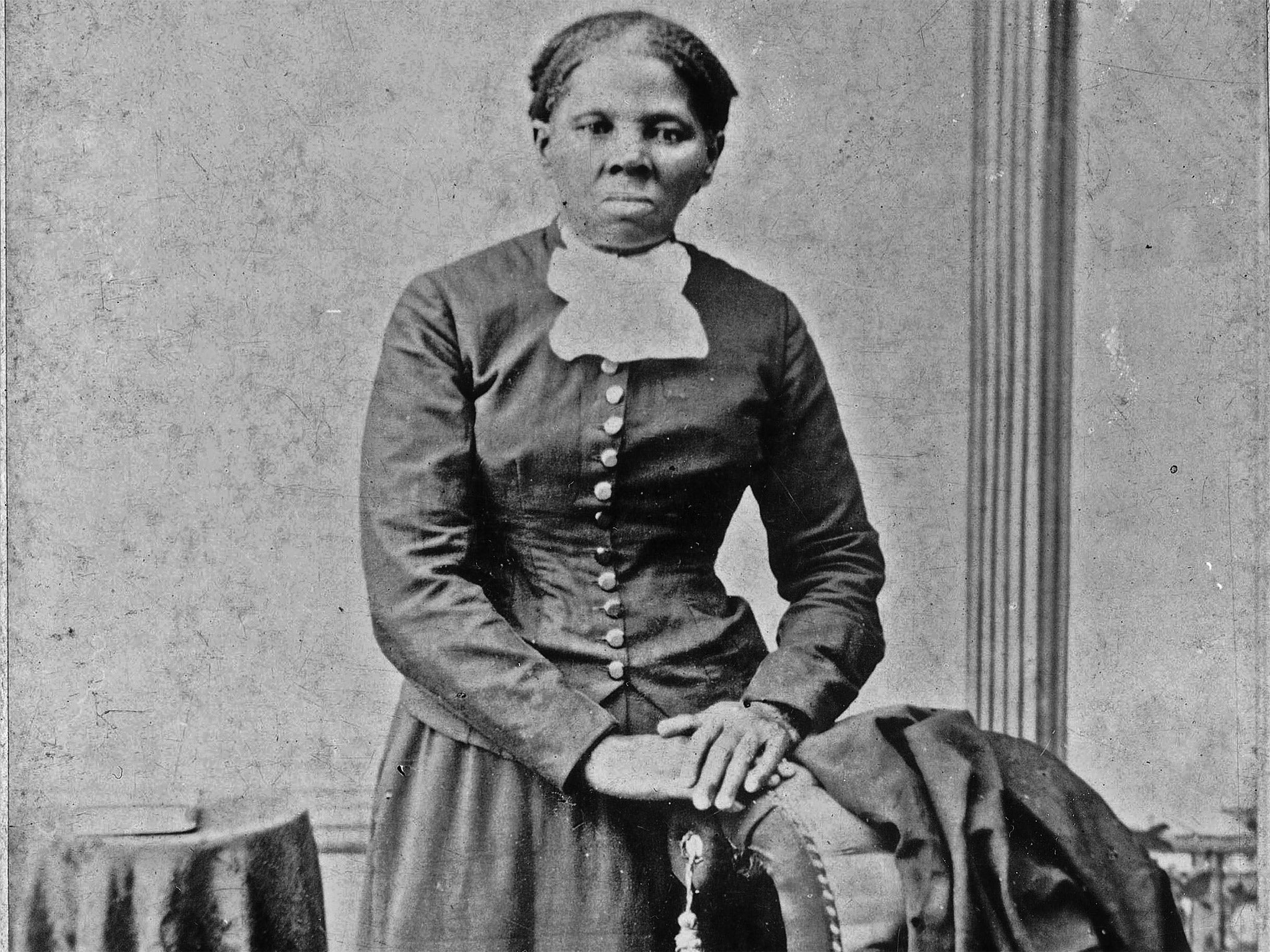

Harriet Tubman, a former slave in the American Civil War era, freed more than 800 slaves from captivity during her lifetime. She was nicknamed “Moses” for her efforts, and it seems almost natural that we should honour her heroics – acts which symbolize the universal desire for freedom – by putting her face on our banknotes.

Although African-Americans are celebrating this new recognition of our 500-year long struggle against white settler colonial violence, the nature of that violence should give us some pause. There is, after all, a troubling relationship between African slaves and money through the history of chattel slavery.

Chattel slavery in the European colonial era was unique two ways from other earlier (and many contemporary) forms of slavery. First, chattel slaves were legally considered property of the ‘owner’. Second, the status of “slave” was passed down from mother to child.

For the US economy before the Civil War, slaves were very important commodities and forms of capital for both individuals and institutions. Enslaved Africans – men and women like Harriet Tubman – were considered equivalent to, and used as, a kind of currency or investment in the early American economy.

Slaves were used to pay debts. Many prominent financial institutions, such as Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase and Aetna, insured or dealt in transactions involving slaves, seizing them from their owners for not paying back loans.

More disturbing than slave insurance, many slave owners banked on the “birthright” (or more appropriately “birth curse”) of slave status to increase their fortunes by breeding enslaved people with each other.

The logic of slave breeding is the same as investment, where one puts capital into a stock, bond or fund to produce more capital. The children of slaves didn’t have to be paid for and could work on the plantation or be sold for profit to others in need of slave labor. This practice became more important in the US after Thomas Jefferson banned slave imports in 1808.

Considering how the slave owners and slave catchers who Harriet Tubman struggled against viewed her and those she freed, putting her face on the currency of the nation that considered her equal to that piece of paper is more of an affront than an honor.

Tubman and those she helped free struggled against the notion that they were no more than tools or assets to be used by racial capitalism for the cultivation of land that they bloodily murdered indigenous peoples for. They struggled against a system where they were told that their highest aspiration was to become a more valuable resource to their masters – in Monopoly terms, a Boardwalk not a Mediterranean Avenue, a Mayfair instead of the Old Kent Road.

If people want to truly honor Tubman and her legacy they should consider how our society can combat the current manifestation of that same slave-as-capital logic. African-American contributions to American culture are consumed and loved by many Americans, but that same love is no longer reflected when African-Americans stand up and resist police brutality against them.

If America learned to love black people as much as they love black culture, that would be a true honour to the life and struggle of Harriet Tubman.

William Jamal Richardson is a PhD student at the Department of Sociology at Northwestern University researching the legacies of settler colonialism in the US. He also is the founder and editor of Rebel Researchers Collective

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks