If Jeremy Corbyn won’t block Brexit, will the Labour Lords step in to provide pro-Remain leadership?

Whatever you think of Corbyn, you have to admire the way he won enthusiastic support from Remainers when his manifesto made clear Brexit was going to happen

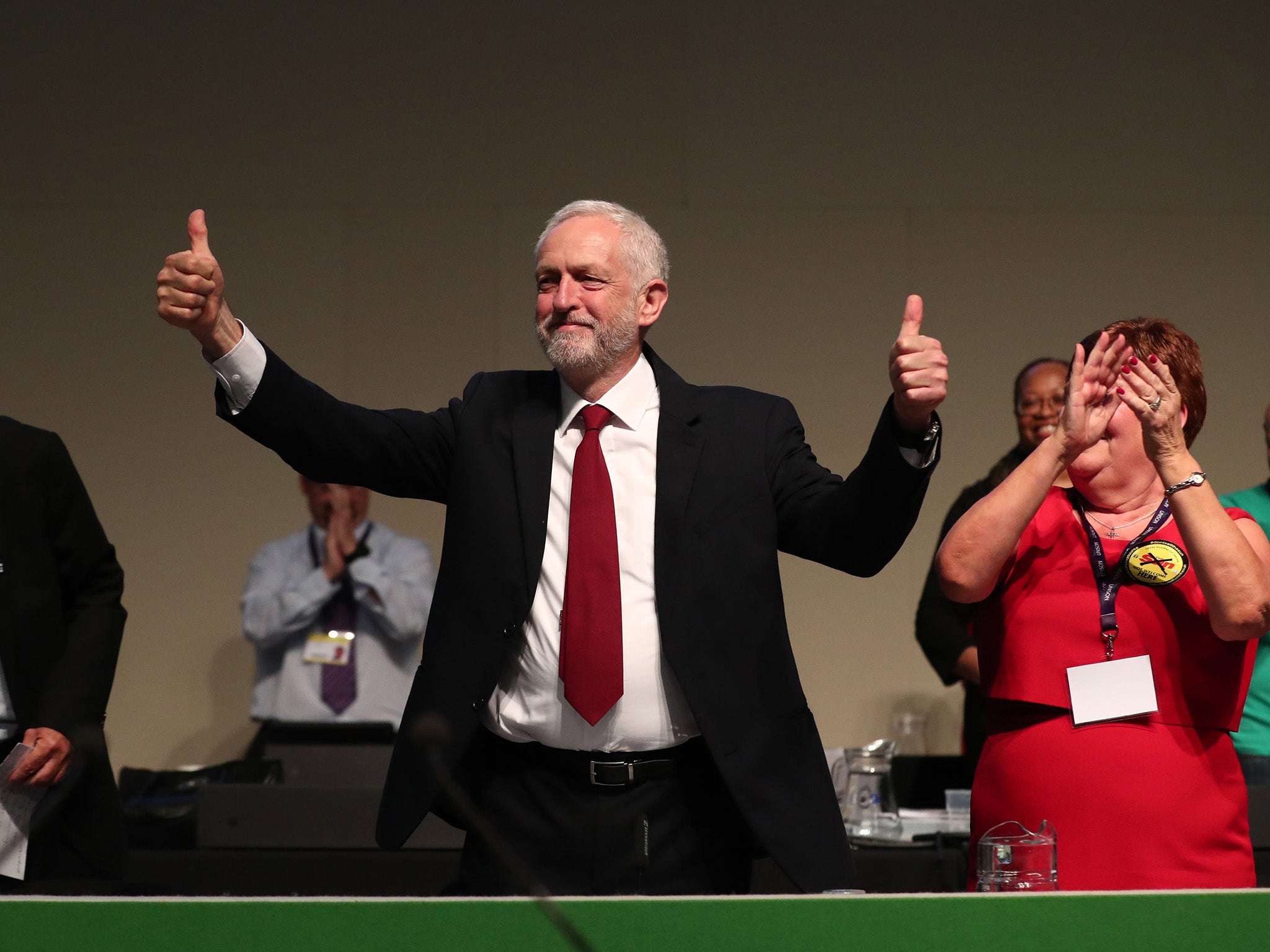

Young people at Glastonbury cheered the Labour leader and sang, “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn.” The adulation is strange, coming from an audience overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit, for a politician who is not overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit.

Indeed, Corbyn was named this week as one of the “Guilty Men” responsible for Britain’s departure from the EU in a bitter polemic by “Cato the Younger”, because of his failure to mobilise the Labour vote in the referendum. The book is modelled on the anonymous diatribe, The Guilty Men, by “Cato”, against those responsible for appeasement in the 1930s. Just to pile irony upon ironies, the principal author of the original was Michael Foot, later a left-wing Labour leader to whom Corbyn was often compared.

Whatever you think of Corbyn, you have to admire the way he won the enthusiastic support of voters who wanted to stop Brexit for a manifesto that said – with one obscure caveat – that it was going to happen. The Sunday after the election, Andrew Marr asked Corbyn: “So you are clear, we are leaving the EU?” And Corbyn replied: “Absolutely.”

The hope of some EU supporters that the hung parliament might open the way to reconsidering Brexit was dashed. Corbyn and John McDonnell even ruled out staying in the single market, although Keir Starmer, the shadow Brexit Secretary, wants to leave it as one of the “options on the table”.

In this, Corbyn and McDonnell are simply accepting the arithmetic of the House of Commons. The Conservatives and the DUP together have a majority, and the DUP has made it clear that it supports not just Brexit but Theresa May’s version of it.

However, the hung parliament has another consequence, which is that it affects the politics of the House of Lords – and the Lords, too, has a vote on Brexit. That is why the Prime Minister’s spokesman was asked about the Salisbury convention this week. The convention is that the Lords won’t block policies that were in the manifesto of the governing party in the Commons. It was invented by Lord Salisbury in 1945 to get round the problem of a huge Conservative majority in the upper house facing Clement Attlee’s government, elected by a landslide in the lower house.

But does it apply if the party that forms a government has failed to win a majority in the Commons? Professor Mark Elliott of Cambridge University argues that it could do. It could be argued that it did apply in 2010-15, on the grounds that the Conservatives and Lib Dems merged their manifestos in the coalition agreement and so had an implied mandate for that.

Prof Elliott argues that the same case can be made for an inter-party agreement that is not a full coalition, such as the imminent Conservative-DUP deal, and that, provided both parties’ manifestos were sufficiently similar, the convention could be held to apply to policies, such as those on Brexit.

That said, it’s a convention, not a law. How it operates in practice depends on what the people who use it think it means. Which is why the most important person in deciding Brexit could be Angela Smith, Lady Smith of Basildon, the Labour leader in the Lords. She in effect decides what the convention means. She spoke about it in the Lords this week, saying that the 1945 convention “in essence held that, given that majority, this House would not vote against manifesto items at Second Reading or introduce wrecking amendments”.

My reading of that is that she feels the convention does not apply, because “given that majority” does not apply. But what she went on to say was even more important. “This House recognises the primacy of the Commons, and that is how we have always conducted ourselves… Your Lordships’ House can advise, scrutinise and propose amendments to the other place, but at the end of the day the House of Commons, as the elected House, is entitled not to accept that advice, however wise we may think it is.” That means, I think, that if the majority in the Commons – the Conservatives plus the DUP – insist on the terms of Brexit as negotiated by the Government, the House of Lords has to accept them.

If Baroness Smith and Baroness Evans, the Conservative leader in the Lords, agree, that is how it will be. Between them, they have the numbers to win the votes in the upper house.

I am sorry to disappoint the crowds cheering Corbyn on the Pyramid Stage, but my understanding is that, although the House of Lords could theoretically wreck Brexit, it won’t actually do it, and nor should it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks