If you think we could have prevented a British ex-Guantanamo Bay detainee from carrying out a suicide attack this week, you're wrong

Surveillance demands considerable resources. As many as two dozen people are needed to keep someone on 24 hour watch. That means only a fraction of those considered to pose a risk can be subject to round the clock monitoring

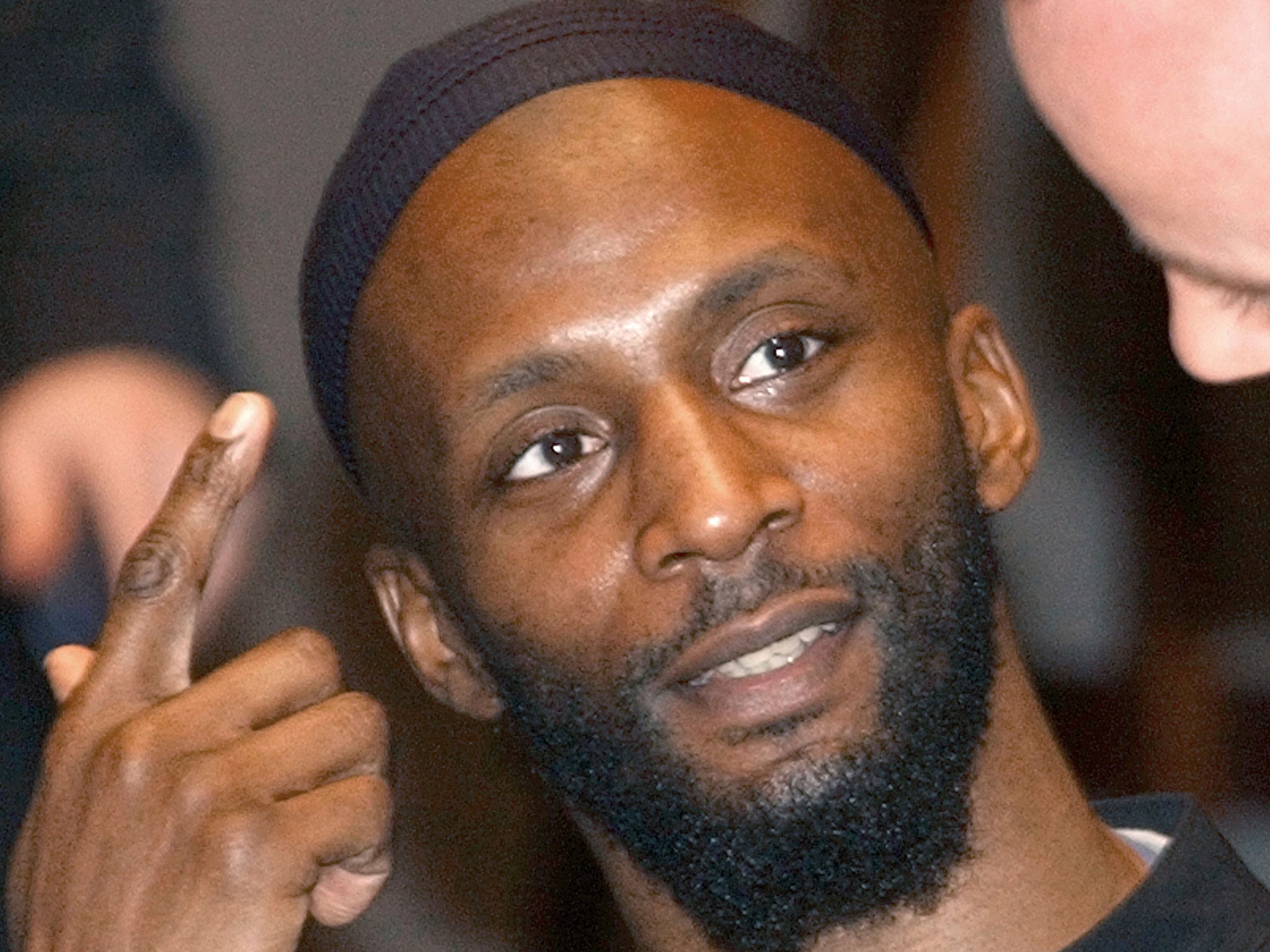

Jamal al-Harith, also known as Ronald Fiddler, appears to have been a career jihadist. In his twenties he allegedly travelled to Sudan with a member of al-Qaeda. In his thirties he was found in Afghanistan in a Taliban prison. Shortly after, he was transferred to Guantanamo Bay where he would spend the next two years. A decade later he left the UK to fight with Isis. And in 2017, at the age of 50, he blew himself up in a car bomb in Iraq.

It’s a compelling story. One that demands answers: why was he freed from Guantanamo? Why weren’t the security and intelligence services monitoring him more closely? Why wasn’t he prevented from travelling to Syria? And why did he leave his wife and five children and kill himself fighting for Isis?

There are many gaps in Jamal’s story, and we may never know what led him to fight and ultimately die in Iraq. What is clear is that the outcome of his journey was never certain.

The majority of those with a history of extremism do not re-engage in violence. The recidivism rate for Guantanamo detainees is just under 18 per cent. That compares favourably with a reoffending rate of around 45 per cent for ‘ordinary’ crime in England and Wales.

Of course, the potential impact of a terrorist attack is significantly greater than that of a robbery or assault. Nevertheless, just because someone was held in Guantanamo does not mean they are automatically at high risk of future involvement in terrorism.

Claims by Tim Loughton MP that “he was clearly a security risk all along” overlook the fact that the risk someone poses can change dramatically. Risk can be influenced by global events, national politics, the evolution of militant networks, and what happens in someone’s personal life. Determining whether an individual is likely to pose a risk next year is difficult, knowing what they may do in ten years’ time is virtually impossible.

But the question remains: why wasn’t he monitored more effectively?

Surveillance demands considerable resources. As many as two dozen people are needed to keep someone on 24 hour watch. That means only a fraction of those considered to pose a risk can be subject to round the clock monitoring.

There are challenges facing electronic surveillance too. Important safeguards limit the types of information that can be monitored. Whilst the sheer volume of electronic data can make it difficult to identify people who may warrant further investigation.

Notwithstanding the practical and legal restrictions around monitoring terrorism suspects, there are important ethical questions. Keeping al-Harith under surveillance for years would have been a significant breach of his civil liberties.

Some would argue he forfeited his human rights when he became involved in extremism. Yet, al-Harith was never proven guilty of a criminal offence, and persistently maintained his innocence. The way he ended his life may cast doubt on his claims, but it was not possible to know what he would go on to do. Under these circumstances, subjecting him to years of surveillance seems likely to undermine the principles the fight against terrorism is supposed to protect, and makes it easier for opponents to accuse the West of hypocrisy.

There will be important lessons from Jamal al-Harith’s case. As they are learnt, policy-makers, academics, and journalists should avoid imposing neat narratives onto complex processes. Nor should they assume it will always be possible to know that someone will make the terrible choice to use violence. Not only does this make it important to continue to improve risk assessment processes, but also to recognise the need for resilience.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks