It’s not what we earn that really matters, but what we spend

Why is a haircut so much cheaper in China, but an iPad costs roughly the same?

A short stroll down the street from my cousin’s apartment in the Chinese city of Guangzhou a man can get a haircut for just 70RMB. At the current exchange rate between sterling and the renminbi that’s around £7. I pay twice that at my local barber in Wimbledon. The quality is not twice as good in London.

But not everything’s cheaper over there. An iPad from Guangzhou’s biggest shopping centre costs roughly the same as it does from the Bluewater shopping mall.

Anyone who has ever gone on holiday to Thailand or Turkey knows that many things are cheaper in poorer countries. The bill at the end of a meal in a local restaurant, for instance, will be significantly smaller. Labour in general is far cheaper. That’s why Britons who are sent by their companies to work in Asia or Africa are sometimes pleasantly surprised to find they can afford to hire live-in maids. Yet other things cost the same, sometimes more, than they do in the West.

Does that feel slightly strange? It felt strange to Gustav Cassel too. In 1918 the Swedish economist put forward the theory of purchasing power parity. Cassel argued that globalised trade should, over time, lead to a convergence in prices in all countries. That means a pound, when converted into another country’s currency, should be able to buy roughly what a pound buys at home. If not, then the exchange rates are out of “equilibrium” and are destined to be squeezed together by the inexorable forces of the free market.

The trouble is that this didn’t happen. Prices stubbornly refused to converge. And exchange rates remained out of equilibrium. In the 1960s two US-based economists, Bela Balassa and Paul Samuelson, independently, came up with the same explanation for why this might be. Balassa and Samuelson pointed out that levels of productivity (output per worker) in the manufacture of traded goods was usually much higher in rich countries. And workers in those sectors commanded high wages relative to countries where manufacturing productivity was lower.

But higher wages in manufacturing drags wages up in non-traded goods sector too in rich countries. If service sector employers, like barbers or restaurants, want to attract people to work for them, they must offer wages that are in touch with those on offer in the local manufacturing sector, even if the level of productivity of these service workers doesn’t necessarily justify it. Where immigration is restricted, foreign competition doesn’t really work in driving down the cost of locally consumed services.

As a theory, Balassa-Samuelson has held up pretty well. And it’s a decent explanation of why the prices of non-traded services like haircuts are so much more expensive in London than Guangzhou, but iPads, which are traded internationally, cost roughly the same. It’s really a reflection of two countries at radically different stages of economic development.

As well as explaining price differences across borders, there are some other implication of this theory. It means that comparing the size of economies at market exchange rates, converted into US dollars for example, is misleading. If a dollar goes further in a country like China or India (because it buys more local services), the overall size of that economy ought to be adjusted upwards when making comparisons with the developed world.

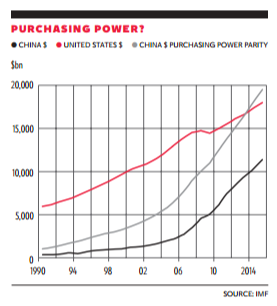

Taking this point on board, economists use special conversions, actually named after Cassel’s Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), to measure an economy’s size. This has dramatic effects. As the chart shows, China’s economy, at market exchange rates, is still considerably smaller than the US. But when adjusted for PPP it is now actually bigger.

Yet there’s a wrinkle. How do we make those PPP adjustments? This is where Angus Deaton, the Princeton economist who last week was awarded the Nobel economics prize, made one of his many standout contributions to the subject. Deaton pioneered the use of household surveys to measure consumption patterns in poor countries.

It’s only when one has a decent understanding of consumption patterns, when you see what the population is buying, that one is in a position to construct an accurate index of national prices and to judge the true purchasing power of a local currency. To put it simply, if everyone in China only bought iPads, they would be making very slow progress. But since the Chinese actually buy a mix of modern technologies as well as cheap local food and services, they are clearly becoming rapidly wealthier.

However, Deaton is not really interested in measuring the aggregate size of economies. His primary interest is measuring poverty and deprivation in the developing world. And PPPs have important implications for this area. India has a third of the world’s extreme poor. Fifteen years ago, Deaton criticised the predominant methodology used by statisticians in Delhi to make estimates of local prices. His recommendations for reform were acted upon, and as a consequence Indian poverty levels were discovered to be significantly higher than thought. The revisions sparked a major political debate in that country about the relationship between poverty and economic growth, thus proving that economists can, sometimes, be of practical use.

Deaton suggests reform should go further. Five years ago, he argued that we should be sceptical of the idea that it’s possible to make comparisons between rich countries and poor countries, even using PPP adjustments. The spending patterns of the populations are simply too different for the exercise to be worthwhile, he argued.

“Unless we understand how the numbers are put together, and what they mean, we run the risk of seeing problems where there are none, or missing urgent and addressable needs,” he wrote in his 2013 book The Great Escape. It’s a salutary lesson.

Deaton’s great contribution has been to make us focus on the underlying meaning of the numbers that underpin our great debates about global poverty and economic growth – and in forcing us to accept that our welfare lies not solely in what we earn, but also in what we consume.

In other words, the price of a Chinese haircut matters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks