Private landlords could be big winners of levelling up – how very Tory

When one in four Tory MPs makes at least £10,000 a year as a private landlord, to what extent will the government ensure basic housing needs are met for tenants?

When the New Labour government of the early 2000s introduced the “decent homes standard” for social housing, few could have imagined how little it would do to improve housing quality for the UK’s poorest families. Not because it was a bad policy; houses for social rent improved dramatically thanks to the injection of money allowing replacement of windows, kitchens and bathrooms to bring them up to basic, universal standards. What was not envisaged, however, was how few people on low incomes would end up living in them.

A large proportion of low-income families who claim housing benefit (which is now paid through universal credit) now live in private rented housing which, to now, has not been covered by similar legislation.

Homes that are damp, mouldy, badly plumbed, poorly maintained or even utterly unfit for human habitation are nevertheless earning their landlords a state dividend via their tenants’ rent payments. Whether you end up with the keys to a private sector hovel controlled by a modern-day slum landlord, or an airy, well-managed social tenancy, has been little more than a matter of luck.

The Levelling Up white paper reveals the government has acknowledged this great divide between housing tenures and is finally doing something about it. A register of private landlords is to be introduced, with rogue operators being thrown off the list.

Legislation will be introduced to ensure that, just like the decent home standard, there is a basic minimum quality to which all private rented properties must adhere, including being “safe, warm and in a good state of repair”. I did say minimum. Tenants will also gain new rights of redress to complain about their homes.

On the surface, what a win. Campaigners have been making the case for well over a decade that private tenants deserve a good standard of living and that if it is paid for by the public purse, through housing benefits, then the government has a responsibility to make that happen too.

Now we’ll see it come to fruition, with approximately 800,000 refitted to bring them up to a decent standard. Ministers say they want to halve the number of poor quality homes by 2030 – that’s two decades after the deadline for the decent homes standard for social rent, but progress nevertheless. The majority of these unfit homes are located in northern constituencies, so there is a clear potential for reward at the ballot box if the government gets this policy right.

So why does it all feel a bit thin? Accuse me of cynicism, but I spy a few get-out clauses. The language used is too nebulous: what exactly, in practical terms, does “safe, warm and in a good state of repair” mean?

There may be more detail in the full white paper, but if (as I suspect) any legislative commitment leaves enough wiggle room to prevent landlords claiming the government is making their business uneconomic, or stringent enough to turf the worst operators out, they will pounce on it.

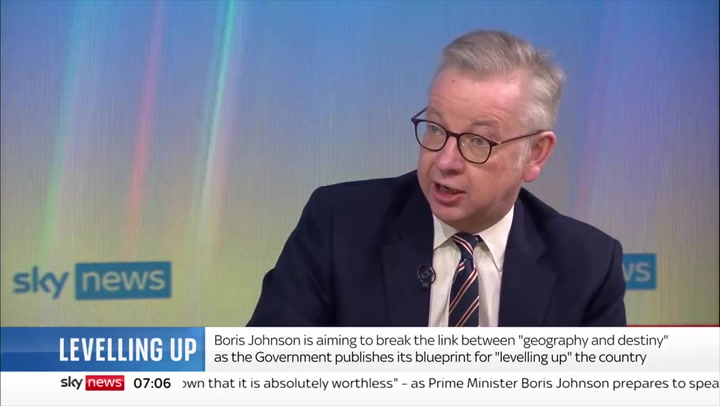

There are more questions: who, or what organisation, will be responsible for monitoring and managing the register of landlords? Michael Gove says new decency standards are to be applied to the whole private rental sector, but will membership of this register also be obligatory?

If it’s not a legal requirement to be part of that register, merely a sort of government crest of good practice, it will only end up benefitting the wealthier households who have the luxury of choice when finding a home to rent. And if membership is not a legal requirement how will the rogue operators be identified and brought into line? They won’t – a sub-market of poor housing at low rents would develop below the line of sight.

The paper seems to show, finally, an understanding of where the deepest problems and inequalities in our housing system lie, but a lack of commitment to facing down private landlords to tackle it. It’s not difficult to work out why that might be.

Research carried out by the campaign group Generation Rent in 2015 found that one in five MPs also makes at least £10,000 a year as a private landlord. An update to that research carried out by the publication National World suggests that in 2021 this may be as high as one in four Conservative MPs.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

How many people involved in drafting this white paper may be directly financially implicated by added costs and expectations on the private rented sector? Even subconsciously, how hard may they resist the introduction of what they may feel is red tape, but that tenants experience as the secure straps of a safety net?

To make a difference to the lives of private renters, in red wall constituencies and beyond, any decent homes standard would have to be enforceable by law. This week a member of the large G15 group of social landlords was found guilty of maladministration and forced to pay compensation after it left a tenant in a home with a leaking roof for three years.

If similar charges are not meted out against commercial landlord groups and even private individuals then it is not equivalent. And if it is not equivalent, then the great gulf between the two tenures persists, even after the government has been seen to do something.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks