The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

As someone who works with stab victims, I know there are complex reasons for our knife crime problem

There are conversations to be had about risk aversion, forward planning and life choices, but it is impossible to neatly dichotomise young people into ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’

Yesterday evening a man in his twenties died after being stabbed in Hackney, where I have always lived. This occurred only hours after another incident nearby, in which a man believed to be in his fifties was pronounced dead after a fight in a shop. These cases have increased the number of violent deaths in London from 48 to 50, in just one day.

While all these deaths are tragic, it is particularly concerning that so many young people are among the number of those killed thus far. A feeling of panic is brewing about youth violence, and there is a palpable sense of helplessness that is spreading among communities, and a fear in the public consciousness.

As well as this there are the long-term effects that loss has upon individuals. We are forced to look inwardly and question how a nation so affluent and globally heralded is failing to effectively contend with people as young as 16 and 17 being stabbed and shot so frequently, and indeed the factors that bring about such a sinister state of affairs in the first instance.

Some commentators highlight the individual responsibility of perpetrators and their families. Violence seems to be easier to process if we caricature all those who have killed as fundamentally ‘evil’, or baselessly dismiss those who have died as a result of it as somehow being ‘gang’ affiliated. The reality is more difficult and nuanced. ‘Normal’ young people have killed without necessarily intending to, and not even those who are wholly blameless and civilian are insulated from violence.

While there are legitimate conversations to be had with young people about risk aversion, forward planning and life choices, it is ultimately impossible to neatly dichotomise the status of victim and perpetrator. For example, some young people who become involved in violence are not necessarily willing participants, and in this context of increasingly scarce services and impenetrably tight eligibility thresholds, some families have found it impossible to access help for their young people despite ardently seeking it.

While we could, as others encourage, consider how musical content or social media might contribute to the normalisation of violence, these narratives are in the end insufficient to explain the root causes – violence has long been a pressing issue before the proliferation of Snapchat, or ‘drill’ music.

It is more important then to consider how other, more deep-rooted factors contribute to violence, such as geography, lack of equality of opportunity and relative socioeconomic inequality. While some detractors may scoff at the mention of the latter, unable to comprehend how abject poverty can exist in a nation so economically developed, the grim realities of disadvantage abound.

While I’m not arguing that all young people involved in violence are necessarily destitute, we must answer important questions: if we as a society have centred our value on currency, what happens to the value ascribed to life when some can’t attain it? What might happen to social norms when fragments of society simply cannot envision how they can surmount their current position in a society so stratified by class, and are forced to look on as others live comfortably? Just as it is incomprehensible how a tragedy such as the fire at Grenfell could occur in a borough as affluent as Kensington and Chelsea, the fact that the young man who died yesterday evening was stabbed so close to a hub of largely unaffordable fashion outlets dubbed Hackney Walk raises important questions about the disparate realities different demographics contend with.

We must also take seriously the effects of a construction of masculinity based on domination, which prohibits the expression of emotions other than anger. Ultimately, the causes of violence are complex and diverse, and reductively pinpointing one singular factor will render insufficient solutions.

But while commentators theorise about causes, the detrimental effects of violence are rampant. Young people such as myself suffer from the cumulative trauma of having lost person after person in their vicinities to violence. It is not difficult to imagine how fear can spread among communities, as longtime residents of affected areas can view images of crime scenes as they are posted online and immediately identify the precise location it happened.

Statistics can obscure the human consequences of violence, but it is important to remember that all who have been killed were individuals with plans and aspirations. There are now empty bedrooms in the homes of grieving families. Survivors might endure PTSD, or find themselves struggling to safeguard themselves from further incidents.

My burning desire to ameliorate these poignant human consequences of violence is why I have chosen to become a youth worker at Redthread – a charity that runs a programme in the emergency departments of hospitals, supporting young people to rebuild their lives after being victims of violence. This desire is also why I encourage all those who are impassioned about this issue to support such essential frontline work.

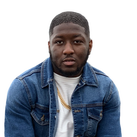

Franklyn Addo is a youth worker, journalist and rapper from Hackney. He studied for a BSc in sociology at the LSE and an MA in cultural studies at Goldsmiths

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks