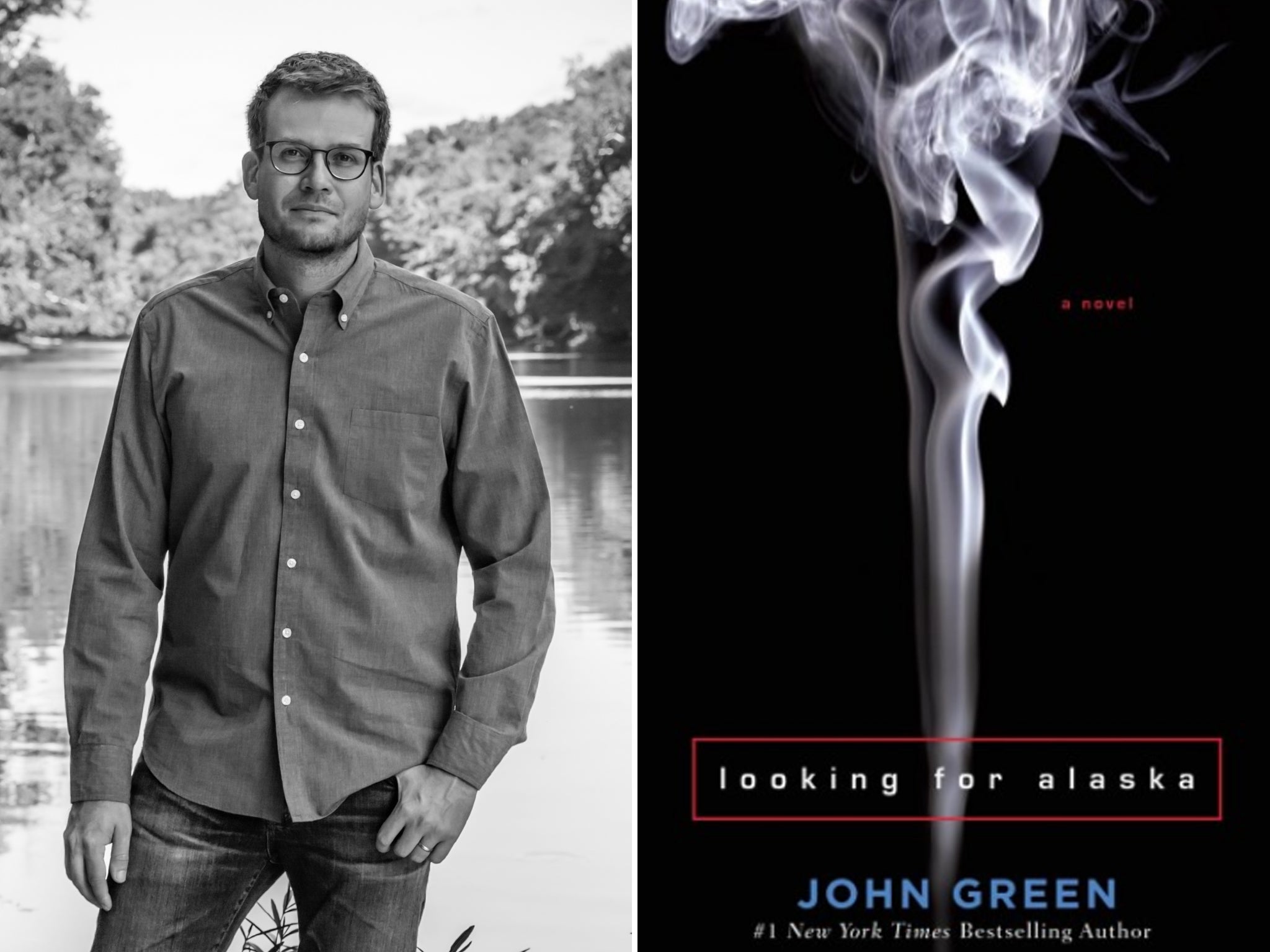

Looking For Alaska is one of the most challenged books in the US. It changed me as a reader – and made me a writer

John Green’s 2005 debut has been a frequent target of book banning efforts for 15 years. The book described in those challenges is not the book I remember

Early in John Green’s 2005 debut novel Looking For Alaska, its teenage protagonist Miles Halter, newly settled at a boarding school in Alabama, sits down for a World Religions class. The teacher, known among students as the Old Man for self-explanatory reasons (he is indeed very old), breathes “with great labor”, and walks so slowly Miles feels he “might die before he ever reached the podium.”

Dr Hyde – the Old Man’s actual last name – promptly lays out the rules of his class: he expects students to do the assigned reading, consistently and on time. Classes will be lecture-style, meaning he will do most of the talking, and his students will sit and listen. “I must talk, and you must listen, for we are engaged here in the most important pursuit in history: the search for meaning,” he says. “What is the nature of being a person? What is the best way to go about being a person?”

Miles realizes the class will not, contrary to what he had hoped, be an easy A. But does he despair? Does he tune out his teacher’s droning? Does he start brainstorming ways to pass the class with the least amount of effort possible?

He does not. Instead, Miles declares Dr Hyde “a genius.” He promptly connects with the class, and his mind is slightly blown.

“In those fifty minutes, the Old Man made me take religion seriously,” Miles narrates. “I’d never been religious, but he told us that religion is important whether or not we believed in one, in the same way that historical events are important whether or not you personally lived through them.”

This scene embodies so much of the essence of Looking For Alaska; a book I remember reading more than 10 years ago – an existential, tender novel, with loss as one of its central themes. But these days, when Looking For Alaska makes the news, it’s not for those characteristics. Green’s debut has become one of the most regularly challenged books in US schools. He addressed the issue in a video as early as 2008. The issue hasn’t gone away – certainly not in our current era, which has seen a record number of books being censored from conservative groups.

The Looking For Alaska described in the context of those challenges is not the Looking For Alaska I remember. (And, lest my memory was failing me, I re-read it before writing this piece.) I came to Looking For Alaska when I was 19, or perhaps a young 20. I was born and raised in France, but at that time, I was studying abroad in London. That was the year I decided I might want to try writing a novel in English one day. I think it had something to do with how for the first time in my life, every time I stepped into a bookstore or a library, all the books were in English. Or maybe I was power-drunk on the exhilaration of living on my own for the first time.

It took me ten years, but I did it. My debut novel in English, a psychological thriller called The Quiet Tenant, will be released in June, in the US and in the UK. When I wonder how I got there (which is often), I think back to that formative year in my life. And, invariably, I think about John Green’s books, which set me on a crucial path both as a reader and as a writer.

Miles spends much of Looking For Alaska on a quest for meaning, both in an academic setting and with his group of smart, misbehaving friends (including the titular Alaska, a female classmate on whom Miles has a crush). That quest is complicated by an unexpected event midway through the book – which I won’t spoil, even 18 years after its publication, but let’s just say that Looking For Alaska is most remembered among fans as a book that was not exactly afraid of breaking readers’ hearts.

Looking For Alaska is a boarding school novel in which the academic experience actually takes up some room: we often tag along with Miles as he listens to his teachers and engages with their material. Academics are more than just a barrier to fun or a logistical challenge; they are, often, the very point. Miles’s friends came to Culver Creek, the boarding school in question, to escape toxic family dynamics or lift themselves out of poverty; Miles, who has loving parents and a financially secure household, came to learn.

For his final exam in World Religions, Miles is asked to pick “the most important questions human beings must answer”, and then, to answer it, using perspectives from Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity. Miles chooses to ponder “what happens to us when we die”, and, reader, we ponder that question with him. A little before the book’s halfway mark, Miles thinks he’s got it figured out – “I finally decided that people believed in an afterlife because they couldn’t bear not to” – but the aforementioned unexpected event halfway through the book prompts him to dig deeper.

Thus, Miles spends a large part of Looking For Alaska trying to answer another question: how will he get out of the labyrinth of suffering? The labyrinth is a metaphor (inspired by Simón Bolívar’s last words: ““Damn it! How will I ever get out of this Labyrinth?”) for the human condition. How do we make sense of life, when it so often insists we suffer?

It is darkly amazing that this cerebral little book, so concerned with philosophy and religion, has become a consistent target of book banning efforts in US school libraries. It appeared on the American Library Association (ALA)’’s lists of the 10 most challenged books in 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016. In September 2022, Green posted a TikTok video stating that a school board candidate in his own former school district was seeking to ban Looking For Alaska “from all schools and libraries in that school district.”

In challenges to Looking For Alaska, one scene comes up often. It happens about halfway through the book, when Miles receives oral sex from a female friend called Lara. The scene is mainly awkward; neither Miles nor Lara have much fun at first. It all concludes rather unceremoniously, with Lara asking Miles: “So, want to do some homework?”

But because the scene names body parts, and directly mentions a sexual act, it is unfortunately primed to be weaponized in book banning efforts.

“Text is meaningless without context,” Green says in a 2016 YouTube video, shortly after Looking For Alaska made the ALA’s shortlist for the third time. “And what usually happens with Looking For Alaska is that a parent shows a particular page of the novel to an administrator, and then the book gets banned without anyone who objects to it having read more than that one particular page.”

Green mentions the oral sex scene, and points out that it is shortly followed by a scene in which Miles kisses the titular Alaska. In Green’s writing, that moment is more chaste, but much more emotionally engaging. That one kiss means infinitely more to Miles than his previous encounter with Lara.

“In context, the novel is arguing, really in a rather pointed way, that emotionally intimate kissing can be a whole lot more fulfilling than emotionally empty oral sex,” Green says in the video.

It’s not just the oral sex scene, some would-be banners might argue. The 2013 ALA ranking of most challenged books did list “drugs/alcohol/smoking” (all of which happen or are consumed within the book’s pages) as one of the motives, alongside “sexually explicit” and “unsuited to age group.” Those, too, happen in context: the first time Miles smokes, he hates it.

Arguably, that’s somewhat besides the point. Looking For Alaska, at its core, is a book that trusts its readers to handle big and small concepts alike – be it the health hazards of smoking or the entire meaning of life.

Maybe I was a little older than the book’s core target demographic when I read it, but it found me at exactly the right time. Nineteen was an age I spent becoming much more than being. I was worried about the future, worried the choices I had to make would make me miserable down the line. In Looking For Alaska, I found the sounding board I didn’t know I needed.

As it turns out, I needed Miles, his big questions, and his determination to answer them. I needed Green’s prose, which is so good at finding a way in and out of heartbreak. I needed sentences like: “We never need be hopeless, because we can never be irreparably broken.” I needed the book’s humor and its witty characters. And, yes, I needed it all to happen in English, a language I was still learning at the time, and which I was turning out to be both very efficient (you can convey things in fewer words and more precisely in English than in my native French) and very beautiful, when someone figured out how to put the right words in the right order.

And this wasn’t just my experience. Check out trade reviews that came out around the time Looking For Alaska was published, and you’ll see that the focus was very much on the story Green was telling, and how he chose to tell it. “What sings and soars in this gorgeously told tale is Green’s mastery of language and the sweet, rough edges of [Miles’s] voice,” Kirkus wrote.

Publishers Weekly deemed the novel “ambitious”, adding: “Theological questions from their religion class add some introspective gloss. But the novel’s chief appeal lies in Miles’s well-articulated lust and his initial excitement about being on his own for the first time. Readers will only hope that this is not the last word from this promising new author.” (It wasn’t; Green has written six books and co-authored two more.)

It seemed pretty obvious to most good-faith readers that Looking For Alaska wanted to talk about love, friendship, and grief, and what happens when two or more of those three collide. The book banners, though, insist on talking about blow jobs. This is not entirely without irony.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks