Rely on the Royals to uphold an unethical foreign policy

The Royal Family acts as an agent and adornment of British policy. It slathers democracies and despotisms alike in a lavish coat of ceremonial whitewash

I have never seen the point of Burberry. In a world aflame for centuries with gorgeous textiles (see the Fabric of India show at the V&A Museum), how did a worldwide consumer cult arise from a drab pattern apparently devised by some suburban Mondrian after a November walk in a sodden Surrey wood? Decades of fashion-conscious money prove me wrong.

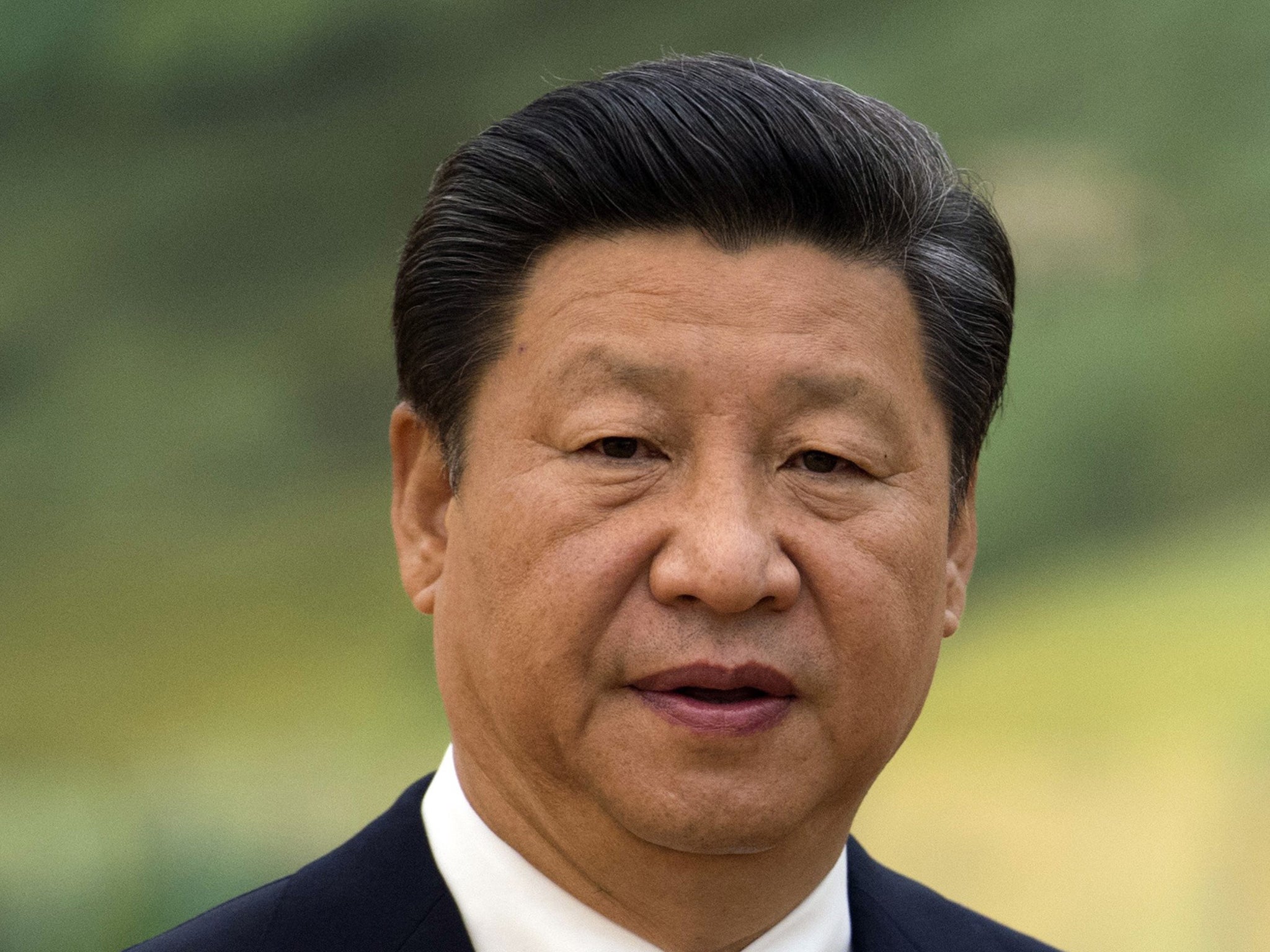

In China, above all, the brand has taken root among the imported signifiers of affluence and taste. So when the Middle Kingdom sneezes, such luxury labels will catch cold. On Thursday, news of a downturn in Burberry sales – above all in Hong Kong – sent the share price into a slide. All the more reason, premium exporters will think, to roll out the red (rather than beige-and-black-checked) carpet when President Xi Jinping arrives next week for the first state visit to the UK by a Chinese leader since Hu Jintao’s in 2005.

A lot rides on President Xi’s autumn breeze around Britain – even though a cantankerous 66-year-old activist with a history of cranky views and off-the-wall interventions in global politics threatens to cause trouble. That would be Prince Charles, who will reportedly boycott the banquet at Buckingham Palace in solidarity with the people of Tibet and his friend the Dalai Lama. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has also threatened to use the banquet to ask questions about human rights.

So he should. Xi’s increasingly iron rule has led over the past two years to a sustained attack on reformist lawyers and campaigners. In that crackdown, at least 245 dissidents have been detained or restrained between July and September alone. Let them rot, the UK seems to say.

George Osborne won high praise from the official media last month when he put trade alone at the heart of his Chinese mission, with a vow to make this country Beijing’s “best partner” in the West. Osborne did claim to have mentioned the case of Ilham Tohti – a moderate Uighur academic sentenced to life for “separatism” in 2014 – when he visited the restive province of Xinjiang in search of investment deals. Still, it currently feels as if the Great Wall will fall before the UK Government makes a stand.

As China’s would-be bestie, Britain has some catching up to do. A relish for Burberry and Scotch in the salons of Shanghai conceals a woefully third-rate business performance. Figures for last year show that British sales to China add up to only half the value of French exports, with Germany – natürlich! – leagues ahead of both. In 2014, China and its 1.35 billion people accounted for 4.8 per cent of UK exports, just over £14bn: well behind the Irish Republic (6.3 per cent), and only marginally ahead of Belgium and Luxembourg (4.3 per cent). The factors behind this shortfall range from the blitz of de-industrialisation overseen in Britain since the 1980s by chancellors of Osborne’s political stripe, to the onerous and discriminatory visa regime for Asian visitors enthusiastically backed by his foreigner-bashing party.

Thus a government that has hampered both human and commercial contact with China now seeks to make up some lost ground through a supine attitude towards the recent upsurge in mass repression. Gao Yu, a 71-year-old independent journalist, disclosed in 2013 that an inner-party paper known as “Document No 9” – formally entitled “Concerning the Situation in the Ideological Sphere” – had sketched out the blueprint for this drive against dissenters who claim “universal” rights.

In April, she received a seven-year sentence for her pains. Earlier this month, Gao had a heart attack in jail. Her lawyer Shang Baojun reports that “she can only deteriorate” if conditions do not improve. Now her appeal has been postponed again. If Corbyn seeks a flagship case, let it be hers.

A country able to make China a more compelling offer than overpriced dun-coloured scarves might hold a stronger hand in the defence of Gao, Tohti and the thousands of peaceful dissidents who share their plight. The repression that followed in the wake of Document No 9 has coincided with stalled growth, stock market crashes and ballooning debt (now 282 per cent of GDP). To partners who wish to pay more than lip service to human rights, this might have brought a time of opportunity. For the UK, it has proved a moment of surrender.

Next week’s royal pantomime will set the seal on that complicity. Xi’s minders have apparently turned up their noses at the proffered turbot, not trusting his stomach with fresh British fish. The President need not worry. He will find only gutted, boneless and kippered local products at the linen-draped table.

A nation that projected undiluted realpolitik on the global stage would not look like such a slippery customer. Britain, however, remains divided between naked self-interest and high‑minded gestures of principle. Thus, after decades of unblushing support for the sanguinary fundamentalists of Saudi Arabia, this week it emerged that the scruples of Justice Secretary Michael Gove have forced his department to withdraw from a £5.9m contract to train prison officers in the kingdom of floggers, stoners and beheaders.

Only this January, flags on UK official buildings flew at half-mast when King Abdullah died. Perfidious Albion, indeed. The Prince of Wales, by the way, shares the selective conscience that one often finds among boycotters. For all his Tibet-inspired history of withdrawal from Chinese events, he rolls up in Riyadh every year or two, supposedly to exert a liberal backstage influence on his Saudi peers.

In February, Charles went again to meet the new King Salman, a few weeks after reformist blogger Raif Badawi had endured the first 50 of his thousand lashes. No more have been inflicted, although the sentence stands. Meanwhile Ali Mohammed al-Nimr – along with two other young Shia protesters – may soon face decapitation and crucifixion for “offences” committed at the age of 17. Time and again, royals and diplomats will timidly “raise concerns”, only for strategically useful despots to dash them to the ground in contempt.

Although it will not mitigate the suffering of a single Chinese free-thinker, the regal welcome for Xi and his team does help to illuminate another secretive elite. The British monarchy commands the support of a large majority at home for its “unpolitical” role, above party or faction. In foreign affairs, the mask soon slips. Whether it approves or not, the Royal Family acts as an agent and an adornment of UK overseas policy and its geopolitical aims. It slathers democracies and despotisms alike in a lavish coat of ceremonial whitewash.

Contacts with the Commonwealth aside, the modern record of state visits amounts to a capsule history of post-imperial British priorities. Repeatedly, the crown follows the money. Naturally, the Gulf monarchies and their treacly buried treasure loom large. Among incoming visitors, King Abdullah arrived from Saudi Arabia in 2007; the Emir of Qatar in 2010; the Amir of Kuwait in 2012, and the President of the UAE in 2013. More intriguingly, presidents of Mexico had the carpets unrolled for them in 2009 and again in 2015.

On occasion, the Queen’s visits correspond to genuine shifts in popular as well as political opinion: say, to South Africa in 1995, Ireland in 2011 or Germany this June. Other royal jaunts hint at intelligent long-term planning with newer allies. I’m glad that Charles and Camilla enjoyed a trip to Colombia last autumn, and would urge anyone else to follow them – although there was one undiplomatic episode when the Prince unveiled a plaque to Admiral Vernon’s failed siege of Cartagena in 1741. On that coast, any English seafarer is and always will be el pirata. From a British perspective, the crown may still appear to offer a neutral focus for loyalty. Abroad, no one doubts that the royal caravan merely trundles between one promising souk and another.

Outside Utopia, imperfect democracies must continue to talk to, and trade with, a spectrum of autocratic or authoritarian states. Yet diplomatic smiles and frowns will never achieve much on their own. Context and circumstance can blunt the sharpest words and deeds. Trade sanctions, for example, have softened Iran but stiffened Russia. The pieces on the chessboard shift from day to day. In China’s case, however, its spasm of economic panic may have opened a brief window for outside pressure. If so, then Osborne’s docility has fluffed a chance.

A warmer appeal to China from its wannabe “best partner” may still encourage exports with a shelf life longer than the latest stripy gaberdine. Next February, the Royal Shakespeare Company will inaugurate a decade-long collaboration with Chinese theatre-makers when it stages Henry IV Parts One and Two and Henry V, in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. This is as official as it gets: Catherine Mallyon, the RSC’s executive director, even accompanied Osborne on his China tour.

Audiences there will witness the progress of the wastrel Prince Hal as he hardens into a pitiless conquering hero who, in Henry V, menaces the besieged citizens of Harfleur with rape, massacre and even the sight of “your naked infants spitted upon pikes”. They will learn that, in Shakespeare’s time and since, the people of this island revered a smart but ruthless warlord who rode roughshod over diplomatic niceties and answered claims of right with fire and sword. Maybe we can be best pals after all.

I have never seen the point of Burberry. In a world aflame for centuries with gorgeous textiles (see the Fabric of India show at the V&A Museum), how did a worldwide consumer cult arise from a drab pattern apparently devised by some suburban Mondrian after a November walk in a sodden Surrey wood? Decades of fashion-conscious money prove me wrong.

In China, above all, the brand has taken root among the imported signifiers of affluence and taste. So when the Middle Kingdom sneezes, such luxury labels will catch cold. On Thursday, news of a downturn in Burberry sales – above all in Hong Kong – sent the share price into a slide. All the more reason, premium exporters will think, to roll out the red (rather than beige-and-black-checked) carpet when President Xi Jinping arrives next week for the first state visit to the UK by a Chinese leader since Hu Jintao’s in 2005.

A lot rides on President Xi’s autumn breeze around Britain – even though a cantankerous 66-year-old activist with a history of cranky views and off-the-wall interventions in global politics threatens to cause trouble. That would be Prince Charles, who will reportedly boycott the banquet at Buckingham Palace in solidarity with the people of Tibet and his friend the Dalai Lama. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has also threatened to use the banquet to ask questions about human rights.

So he should. Xi’s increasingly iron rule has led over the past two years to a sustained attack on reformist lawyers and campaigners. In that crackdown, at least 245 dissidents have been detained or restrained between July and September alone. Let them rot, the UK seems to say.

George Osborne won high praise from the official media last month when he put trade alone at the heart of his Chinese mission, with a vow to make this country Beijing’s “best partner” in the West. Osborne did claim to have mentioned the case of Ilham Tohti – a moderate Uighur academic sentenced to life for “separatism” in 2014 – when he visited the restive province of Xinjiang in search of investment deals. Still, it currently feels as if the Great Wall will fall before the UK Government makes a stand.

As China’s would-be bestie, Britain has some catching up to do. A relish for Burberry and Scotch in the salons of Shanghai conceals a woefully third-rate business performance. Figures for last year show that British sales to China add up to only half the value of French exports, with Germany – natürlich! – leagues ahead of both. In 2014, China and its 1.35 billion people accounted for 4.8 per cent of UK exports, just over £14bn: well behind the Irish Republic (6.3 per cent), and only marginally ahead of Belgium and Luxembourg (4.3 per cent). The factors behind this shortfall range from the blitz of de-industrialisation overseen in Britain since the 1980s by chancellors of Osborne’s political stripe, to the onerous and discriminatory visa regime for Asian visitors enthusiastically backed by his foreigner-bashing party.

Thus a government that has hampered both human and commercial contact with China now seeks to make up some lost ground through a supine attitude towards the recent upsurge in mass repression. Gao Yu, a 71-year-old independent journalist, disclosed in 2013 that an inner-party paper known as “Document No 9” – formally entitled “Concerning the Situation in the Ideological Sphere” – had sketched out the blueprint for this drive against dissenters who claim “universal” rights.

In April, she received a seven-year sentence for her pains. Earlier this month, Gao had a heart attack in jail. Her lawyer Shang Baojun reports that “she can only deteriorate” if conditions do not improve. Now her appeal has been postponed again. If Corbyn seeks a flagship case, let it be hers.

A country able to make China a more compelling offer than overpriced dun-coloured scarves might hold a stronger hand in the defence of Gao, Tohti and the thousands of peaceful dissidents who share their plight. The repression that followed in the wake of Document No 9 has coincided with stalled growth, stock market crashes and ballooning debt (now 282 per cent of GDP). To partners who wish to pay more than lip service to human rights, this might have brought a time of opportunity. For the UK, it has proved a moment of surrender.

Next week’s royal pantomime will set the seal on that complicity. Xi’s minders have apparently turned up their noses at the proffered turbot, not trusting his stomach with fresh British fish. The President need not worry. He will find only gutted, boneless and kippered local products at the linen-draped table.

A nation that projected undiluted realpolitik on the global stage would not look like such a slippery customer. Britain, however, remains divided between naked self-interest and high‑minded gestures of principle. Thus, after decades of unblushing support for the sanguinary fundamentalists of Saudi Arabia, this week it emerged that the scruples of Justice Secretary Michael Gove have forced his department to withdraw from a £5.9m contract to train prison officers in the kingdom of floggers, stoners and beheaders.

Only this January, flags on UK official buildings flew at half-mast when King Abdullah died. Perfidious Albion, indeed. The Prince of Wales, by the way, shares the selective conscience that one often finds among boycotters. For all his Tibet-inspired history of withdrawal from Chinese events, he rolls up in Riyadh every year or two, supposedly to exert a liberal backstage influence on his Saudi peers.

In February, Charles went again to meet the new King Salman, a few weeks after reformist blogger Raif Badawi had endured the first 50 of his thousand lashes. No more have been inflicted, although the sentence stands. Meanwhile Ali Mohammed al-Nimr – along with two other young Shia protesters – may soon face decapitation and crucifixion for “offences” committed at the age of 17. Time and again, royals and diplomats will timidly “raise concerns”, only for strategically useful despots to dash them to the ground in contempt.

Although it will not mitigate the suffering of a single Chinese free-thinker, the regal welcome for Xi and his team does help to illuminate another secretive elite. The British monarchy commands the support of a large majority at home for its “unpolitical” role, above party or faction. In foreign affairs, the mask soon slips. Whether it approves or not, the Royal Family acts as an agent and an adornment of UK overseas policy and its geopolitical aims. It slathers democracies and despotisms alike in a lavish coat of ceremonial whitewash.

Contacts with the Commonwealth aside, the modern record of state visits amounts to a capsule history of post-imperial British priorities. Repeatedly, the crown follows the money. Naturally, the Gulf monarchies and their treacly buried treasure loom large. Among incoming visitors, King Abdullah arrived from Saudi Arabia in 2007; the Emir of Qatar in 2010; the Amir of Kuwait in 2012, and the President of the UAE in 2013. More intriguingly, presidents of Mexico had the carpets unrolled for them in 2009 and again in 2015.

On occasion, the Queen’s visits correspond to genuine shifts in popular as well as political opinion: say, to South Africa in 1995, Ireland in 2011 or Germany this June. Other royal jaunts hint at intelligent long-term planning with newer allies. I’m glad that Charles and Camilla enjoyed a trip to Colombia last autumn, and would urge anyone else to follow them – although there was one undiplomatic episode when the Prince unveiled a plaque to Admiral Vernon’s failed siege of Cartagena in 1741. On that coast, any English seafarer is and always will be el pirata. From a British perspective, the crown may still appear to offer a neutral focus for loyalty. Abroad, no one doubts that the royal caravan merely trundles between one promising souk and another.

Outside Utopia, imperfect democracies must continue to talk to, and trade with, a spectrum of autocratic or authoritarian states. Yet diplomatic smiles and frowns will never achieve much on their own. Context and circumstance can blunt the sharpest words and deeds. Trade sanctions, for example, have softened Iran but stiffened Russia. The pieces on the chessboard shift from day to day. In China’s case, however, its spasm of economic panic may have opened a brief window for outside pressure. If so, then Osborne’s docility has fluffed a chance.

A warmer appeal to China from its wannabe “best partner” may still encourage exports with a shelf life longer than the latest stripy gaberdine. Next February, the Royal Shakespeare Company will inaugurate a decade-long collaboration with Chinese theatre-makers when it stages Henry IV Parts One and Two and Henry V, in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. This is as official as it gets: Catherine Mallyon, the RSC’s executive director, even accompanied Osborne on his China tour.

Audiences there will witness the progress of the wastrel Prince Hal as he hardens into a pitiless conquering hero who, in Henry V, menaces the besieged citizens of Harfleur with rape, massacre and even the sight of “your naked infants spitted upon pikes”. They will learn that, in Shakespeare’s time and since, the people of this island revered a smart but ruthless warlord who rode roughshod over diplomatic niceties and answered claims of right with fire and sword. Maybe we can be best pals after all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks