Russian plane crash: Decision to ground planes made President Sisi’s visit uncomfortable – but he shouldn't have been invited at all

The Cameron government chooses to value the solid benefits of trade between nations above the less easily measured effects of cosying up to dictators

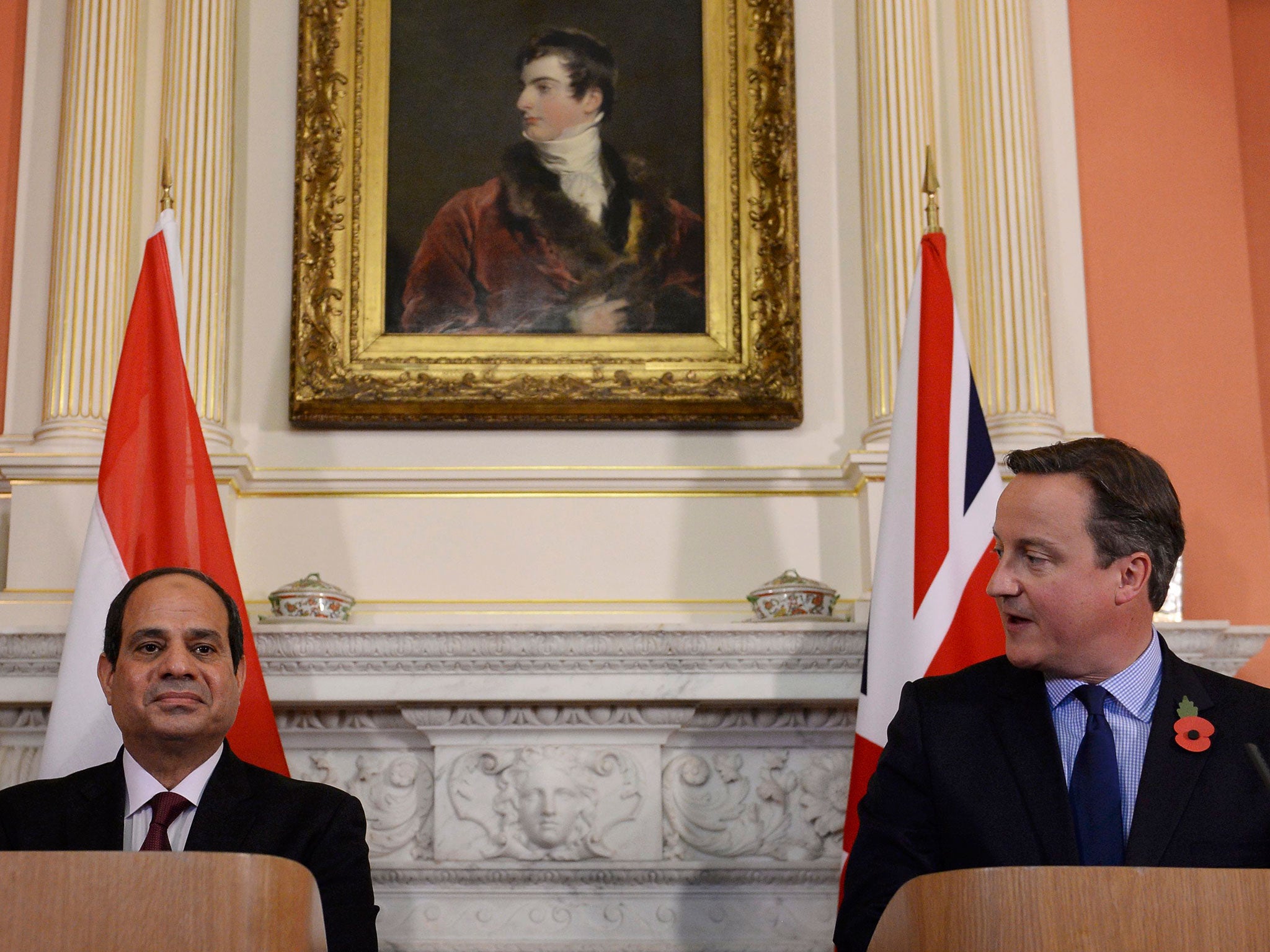

David Cameron standing alongside a foreign ruler with a dire civil rights record is becoming a regular sight. First there was the President of China, Xi Jinping, then President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan, and now Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

Diplomatically, this visit is the most difficult of the three, because of the shadow cast over it by the disaster in the Sinai desert. If British intelligence is correct, and it was a bomb that brought down the Russian Airbus 321-200 on Saturday, killing 224 people, the implications are of profound concern. Airport security has been tightened up across the world since the 11 September 2001 attacks, adding to the expense and stress of air travel, and yet it appears that Isis was able to smuggle a bomb aboard a Russian passenger aircraft before it took off from Sharm el-Sheikh. The Foreign Office grounded all planes in and out of the resort on Wednesday, with flights to the UK resuming today.

This could not have happened at a trickier time for the diplomats responsible for UK relations with Egypt. The tourist trade is vital to Egypt’s economy, and Sharm el-Sheikh is a favourite destination for British holiday makers. Yet on the very day that President Sisi arrived in London, the British essentially cut off one of Egypt’s most valuable sources of income.

Though President Sisi was emollient when he appeared alongside David Cameron in Downing Street, behind the scenes the Egyptians are thought to be offended that they were not forewarned of the British decision, and at the implication that they cannot be trusted to handle security at their airport.

Yet for all the diplomatic embarrassment, and the inconvenience to thousands of British tourists now stranded in Sharm el-Sheikh, realistically the Government had no choice. If Isis was indeed able to smuggle a bomb into the hold of one aircraft, it can do it again, until whoever is doing it is caught.

The catastrophe in the desert relates to another basic question, which is whether David Cameron should be playing host to President Sisi at all.

Mr Sisi professes to have brought stability to his nation, after leading a military coup against the democratically elected – though hardly competent – government of the Muslim Brotherhood. That claim is highly dubious. Not only was Mr Sisi’s place in power cemented on top of the worst massacre in Egypt’s recent history, in which up to 1,000 Brotherhood supporters were murdered in Rabaa square; the extraordinary campaign of repression that continues to this day has swollen the ranks of extremist organisations both within Egypt and outside its borders. Mr Sisi claims that the Brotherhood – despite its record of decades of peaceful engagement in politics – is a “terrorist” organisation. The publication of a British report into whether such allegations hold up, expected to answer with an emphatic “No”, has been delayed for months, allegedly for fear of offending our new “allies” in the fight against Isis. If such allegations are correct, they betray a shameful level of spinelessness, and make the UK too complicit for comfort in Mr Sisi’s war on the organisation he deposed from power.

The Cameron government chooses to value the solid benefits of trade between nations above the less easily measured effects of cosying up to dictators. This may be good for business, but it is cynical, and likely to backfire in the long term. All the current diplomatic awkwardness could have been avoided by the simple and honourable expedient of not inviting Mr Sisi in the first place.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks