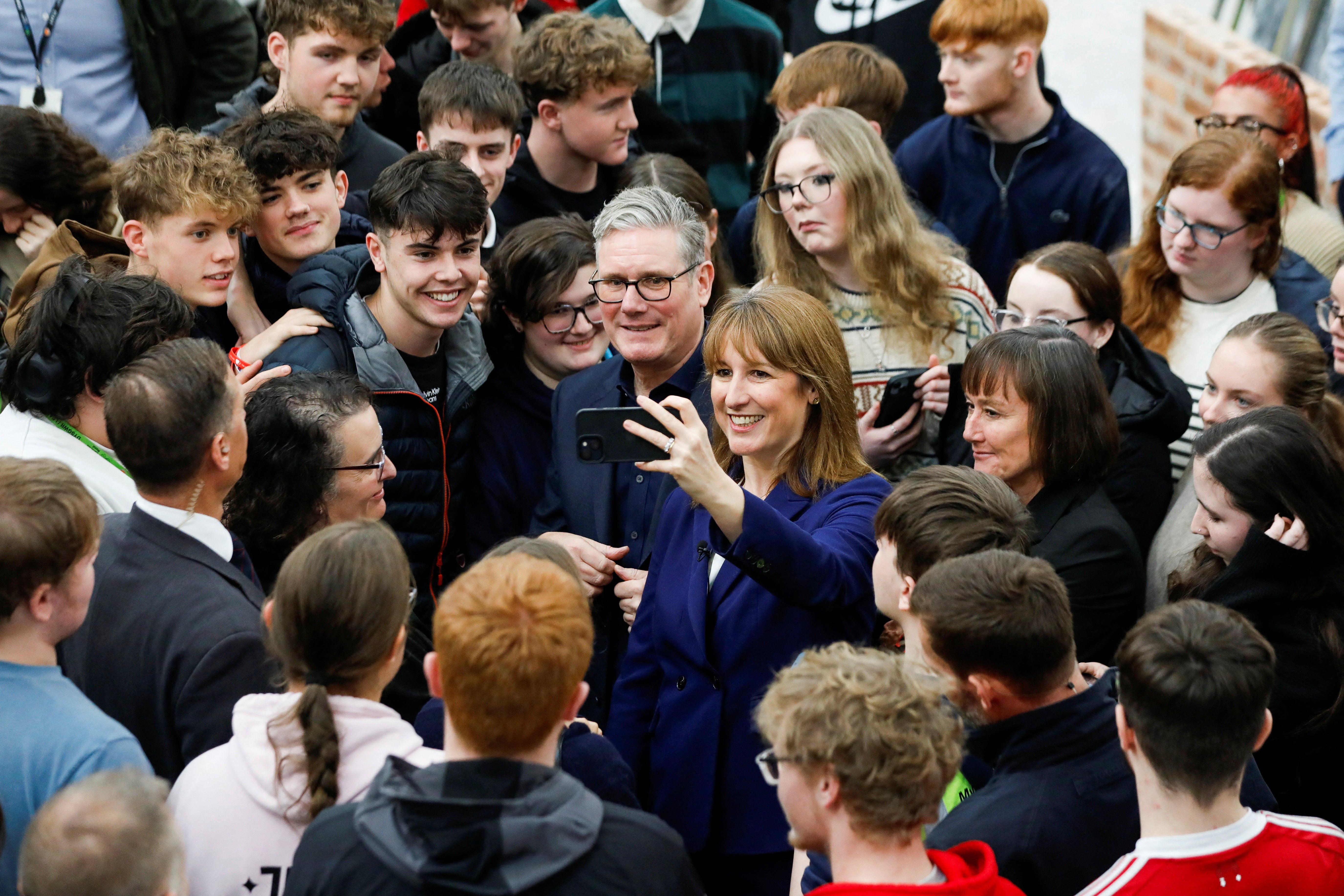

Starmer has another problem – young people are leaving Britain in droves

The prime minister may be pleased that net migration has seen a dramatic drop, writes Chris Blackhurst. But the sting in the tail is who is choosing to leave Britain for a life elsewhere and what they are taking with them as they leave

The latest net migration figures should afford Keir Starmer and his ministers a certain satisfaction. They’re sharply down, a rare bright spot amid the gloom surrounding the seemingly never-ending battle against the Channel crossings and the advancement of Reform UK and Nigel Farage.

Except in one, perhaps telling respect. Young people have had enough, and are leaving in their droves. A net 110,000 16- to 34-year-olds emigrated from Britain in the year to March, according to the Office for National Statistics, amounting to two-thirds of all departing Britons.

By contrast, among the older age groups, those quitting were relatively slight in number or the figure was actually net-positive, meaning that virtually all of the country’s overall loss of 112,000 Britons was among the under-35s.

In broad terms, the over-35s are not leaving – or not to anything like the same extent – and many of those who have previously left are returning. That cannot be said for the younger cohort.

The right have been quick to seize upon the “exodus” as evidence that young people are being driven away by Labour’s high-tax regime. But, bearing in mind that these are figures from the year to March, it is not clear which taxes they might have been fleeing from. Labour’s first Budget was not until the end of October 2024, and any changes Rachel Reeves made that directly affected this cohort did not kick in until April this year.

It’s also the case that few of those measures were aimed specifically at that age group. If onerous taxes were to blame, they were more likely the result of the previous Tory administration.

Still, it was apparent where Labour was intent on taking the country, as was reinforced by Reeves’s second Budget earlier this week.

From her first Budget, in October last year, the hike in employers’ national insurance won’t have helped; it saw many employers postpone hiring and scale back the number of permanent recruits, with school-leavers and graduates in the firing line. The depressed jobs market, especially for the young, is undoubtedly a key influence. As are the increased cost of living and the unaffordability of mounting the property ladder, particularly in the southeast of England.

Reeves’s latest Budget freezes both tax and student loan thresholds, which will result in young people having to pay income tax and pay back their student loans sooner. These factors are likely to have an impact – the next set of annual net migration numbers will be interesting, and possibly depressing for Starmer and Co.

There are other issues at play, aside from taxation. The traditional path – either school and then career, or school, university and career, all while remaining in Britain, close to home – has shifted. Technology, the accessibility of wifi, and the ease of communicating via video calls and phone calls via Teams, Zoom, and WhatsApp, enable people to work from pretty much anywhere. Add in the improvements in transport, with far more frequent, quicker flights, and those who choose to live abroad are not so cut off as they used to be. They can function and earn remotely.

It's a phenomenon that is having an effect. “Speaking to immigration lawyers, what was keeping them busy was people working remotely in countries where they didn’t have immigration permission to do so,” says Madeleine Sumption, the director of Oxford University’s Migration Observatory.

Some countries, notably in the Middle East, are holding out the prospect of work. In Australia, the youth unemployment rate is under 10 per cent, and Britons can take advantage of the working holiday visa scheme – in terms of nationality, they’re the fastest-growing group of people securing these visas, up 80 per cent from the previous year.

The prevailing view is that they are going because they can. Jobs are difficult to find here; prices are high; housing, owned or rented, is expensive. So why not look elsewhere? They can travel and experience another part of the world.

Things change when people get older and wish to settle down; when the wish for a proper career kicks in, and perhaps the desire to have children. Then they are tied. It’s evident in the drop in the number of emigrants in the over-35 cohort, and the number of those returning: they’ve had their freedom, their fun, and now they want to come home.

That has been made all the more possible, and continues to be, by modern communication. Other parts of the world are also catching up – in many cases, overtaking Britain in terms of living standards and lifestyle. They’re sunnier and warmer, too, which is undoubtedly a major determinant.

The world has become smaller, businesses straddle continents and are interlinked, English is a common language; much more, today, is feasible and accessible. And acceptable – the notion of our grown-up children heading abroad for long periods is now standard, in a way that it never was before.

All this is readily explained, and may provide some comfort to the government. It’s not all young people, but some, and many of those that do leave will return. Meanwhile, plenty of their counterparts from overseas want to come to Britain, to work and to study.

The underlying niggle, though, is that something else is bearing down, which is a palpable sense of drift. It existed pre-Covid, but has hardened since then: a feeling of hopelessness, of Britain no longer having an automatic allure. Currently, we’re a nation shrouded in negativity, which is amplified by social media; for those just starting out in their lives, having left school or university, that could be weighing heavily.

Judging by these ONS figures, and looking ahead to next year’s, ministers, in short, might want to begin thinking of reasons why young people should stay – and fast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks