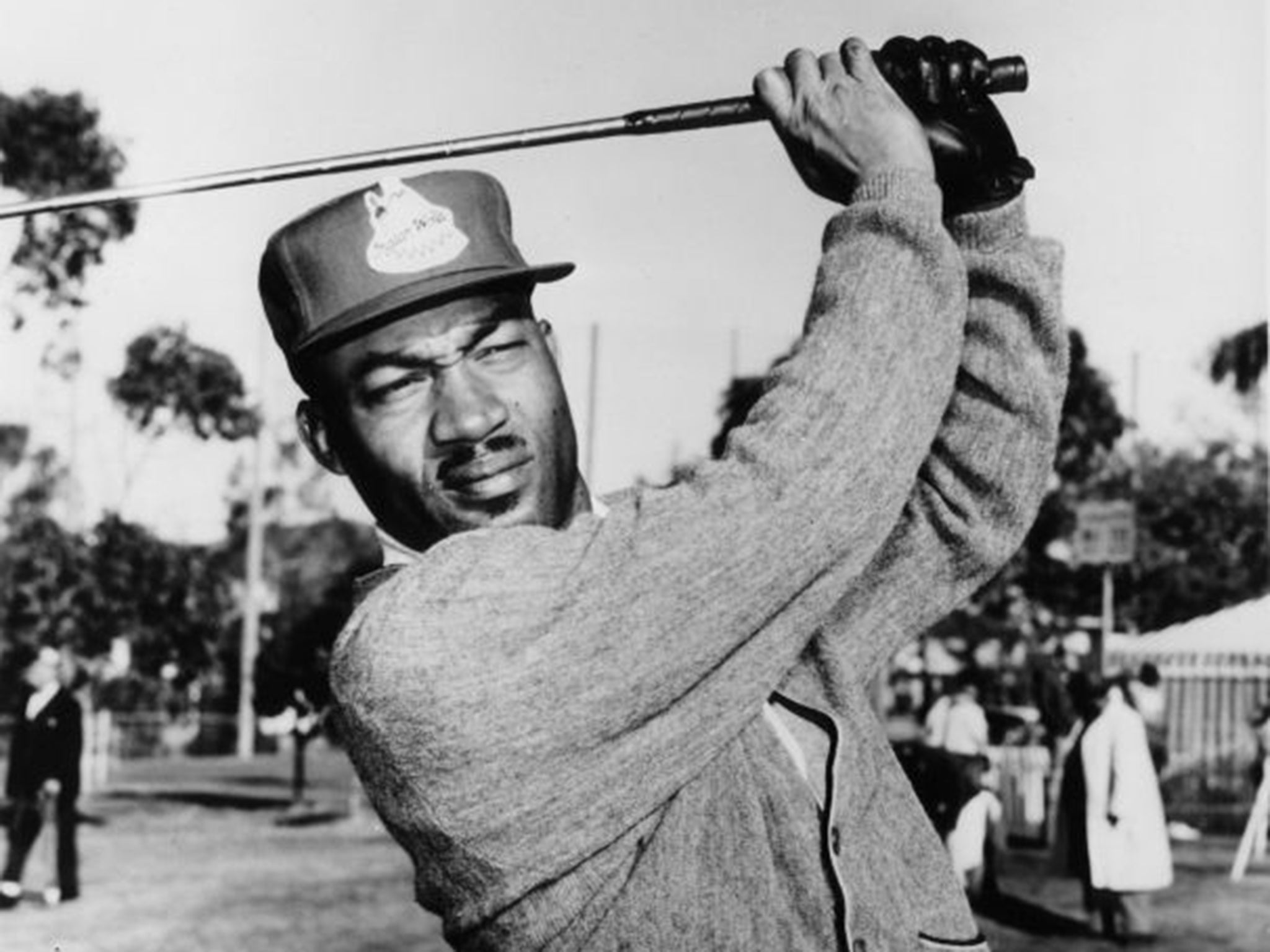

The road to equality was a long and lonely one for Charlie Sifford

Out of America: Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks are being honoured this month, but the golfer, who has just died, also merits a place in history

February is officially Black History Month in America – and when it comes to the struggle for civil rights, 2015 is delivering with a vengeance. Selma, Ava DuVernay’s thrilling film about the historic march that led to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, is up for Best Picture at the Oscars. The fascinating private papers of Rosa Parks, a heroine of the movement, have just been made public. And Charlie Sifford died, at the age of 92.

Unless you’re a golf fan, you’ve probably never heard of him. But, as the first black player admitted to the PGA tour, Sifford has his own separate place in the civil rights story. It may be hard to imagine, in this age of Tiger Woods, but golf, with its encrusted habits and country-club ethos, was about the last major US professional sport to abandon the colour barrier.

Not until 1961 – thanks mainly to a barrage of lawsuits led by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People civil rights advocacy group – did the PGA drop its “Caucasian clause”, limiting membership to whites. And even then many tournaments in the South, including in Sifford’s native North Carolina, wouldn’t have him. By the time he was at last permitted to measure himself against golf’s white elite, he was 38 and past his best. Even so, he went on to win a couple of PGA events. “I really would like to know how good I could have been with a fair chance,” he mused years later.

As it was, his battle to gain acceptance was an ordeal that would have broken lesser men. He couldn’t eat or change his clothes alongside his fellow competitors. In the early days, he once walked on to the first green to find excrement in the cup. Later, spectators would sometimes hide his ball, or knock it into the rough. But he put up with everything, and prevailed.

At the same time as Sifford was trying to get his tour card, Parks was suffering her own and far better known indignities. Yet, unless you’re a real expert on civil rights history, she has always come across as a rather one-dimensional figure: the meek and modest seamstress, sitting quietly in the rear section reserved for coloured people on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, who refused to give up her seat for a white passenger.

Her defiance, one assumed, was born of sheer exhaustion after a long and tiring day’s work, rather than from rage at how she was being treated. But her papers, which have just been made public at the Library of Congress in Washington, show how wrong first impressions can be. For the real Rosa Parks, the activist who like Sifford had always been furious at the indignities heaped upon their race, 1 December 1955 was the day that her patience finally ran out.

“I had been pushed around all my life,” she wrote shortly afterwards, “and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it any more.” The price she paid was heavy. Both Parks and her husband lost their jobs, and for a while were reduced to poverty.

Her strong feelings were apparent from almost her earliest conscious years, as a young girl growing up in rural Alabama who watched her grandfather as he boarded up the windows from the inside, and stood guard with a shotgun against the marauding Ku Klux Klan.

“I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer,” she wrote in a later autobiographical note. “He declared that the first to invade our home would surely die.”

The documents reveal disappointment, too – that her fellow blacks had not risen up against the oppression long before. Instead, she laments, “Such a good job of ‘brain washing’ was done on the Negro, that a militant Negro was almost a freak of nature to them, many times ridiculed by others of his own group.”

In fact, there was little realistic alternative; violence would surely have begotten violence in return, and broader national sympathy might have been lost. That was why Martin Luther King’s protest movement was explicitly non-violent; King knew full well that images of dogs, bull-whips and tear gas unleashed upon peaceful demonstrators would do far more for his cause than violent resistance.

And so it was decades earlier, in arguably America’s first great civil rights breakthrough: not the historic 1954 Supreme Court ruling that segregated schooling violated the US constitution, but seven years before that, when Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier in Major League Baseball, a sport at least as hidebound as golf, albeit far more popular.

Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, knew full well the uproar his move would cause and chose his first black player with great care. Not only was Robinson an electrifying player. He also, Rickey judged, had the strength of character to withstand the insults and harassment he would face from fans and fellow players alike.

He told Robinson he must not rise to the bait. “So you want a player who doesn’t have the guts to fight back?” No, Rickey responded; “I want a player who’s got the guts not to fight back.” Rickey was vindicated on all counts. Robinson endured everything, and soon became one of the game’s most beloved figures. The Dodgers flourished, while baseball as a whole could draw on a new well of fantastic talent.

Charlie Sifford was often described as the Jackie Robinson of golf – but operating in circumstances perhaps even tougher, playing the loneliest sport, without manager or sponsor, forced to do everything himself.

And, whatever her rage inside, Rosa Parks in her own way was a Jackie Robinson. Not just her defiance but her quiet human dignity have made her an eternal symbol of the civil rights movement. Those qualities, too, were the hallmark of the Selma marchers, especially during the first march on “Bloody Sunday”, when state and local police made martyrs of the 600 peaceful participants. If Selma wins Best Picture on 22 February, Black History Month 2015 will be complete.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks