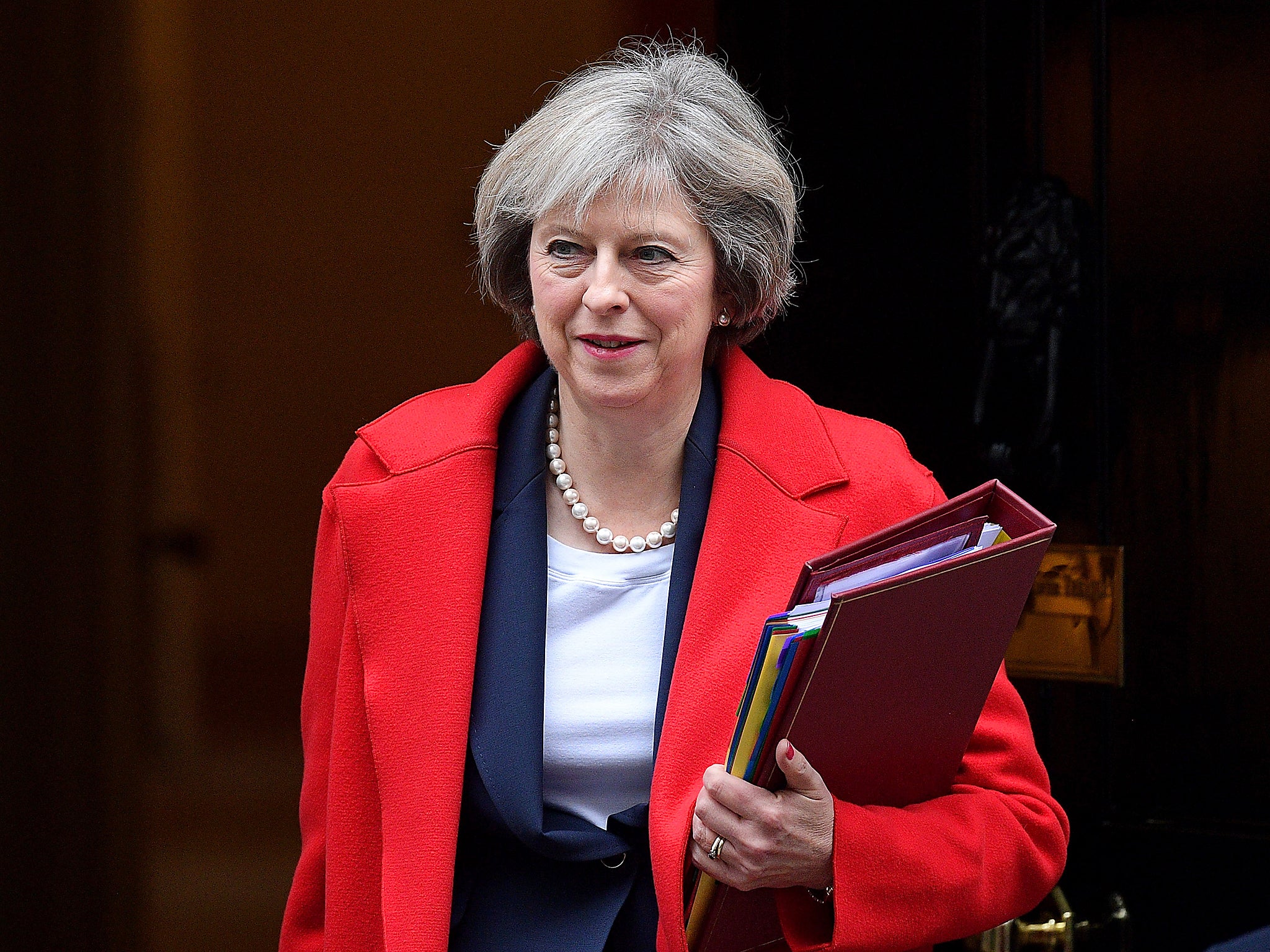

Theresa May is operating at the limits of her competence – her po-faced response to Trump and Farage underlined that

She faced down Boris Johnson over water cannons for London, and then had the Machiavellian bravado to appoint him Foreign Secretary. That seemed strategic, even if the cards haven't played out yet – but some of her other choices look shoddy and unencouraging

It was when Theresa May addressed the massed ranks of Britain’s employers at the Confederation of British Industry this week that the doubts – my doubts – really set in. Her eye-catching proposal, on first entering No 10, that workers should be represented on company boards had been watered down to the point of insignificance. There were, she said, many different ways in which employees could make their voices heard, including workers’ councils and less formal routes.

But the straightforward concept of workers sitting on boards as of right – a provision that has hardly hobbled German business – was not there. The omission was just one aspect of the distinctly friendlier tone she took towards the Brexit-related concerns of business, a change enthusiastically hailed by the Financial Times as a “recalibration”.

What for employers may be a welcome recalibration, however, looks to me – and probably to many rank-and-file workers and their advocates – like a rather large U-turn executed under pressure from those who remain rich and powerful, despite the excesses and mistakes of recent years. The Theresa May who first stood in Downing Street proclaiming a message of One Nation “I am on your side” Toryism seemed to have turned before our eyes into a standard-issue free-market Conservative.

At which point it might perhaps be worth revisiting the benevolent glow that enveloped Theresa May in her first months and asking how much longer this will last. Is a shadow, perhaps, starting to settle over her prime-ministership?

The enthusiasm that met May in her first weeks is understandable. The country had been essentially without leadership since the EU referendum and David Cameron’s summary resignation. The disarray among leading Brexiteers only reinforced a sense of almost total constitutional breakdown. When Theresa May saw off her last rival for the party leadership – after Andrea Leadsom was skewered in a newspaper interview – the overwhelming response was not concern that a democratic process had been pre-empted, but relief that someone so evidently sane and sensible was prepared to take the job.

There were other positives to accentuate. That May had been the longest serving Home Secretary since whenever offset many of the qualms Brexiteers might have harboured about her formal position as a Remainer. That first speech outside Downing Street was embraced as a rejection of the old-boy chumminess of the Cameron government, a turn towards opportunities and aspirations for all, and a recognition that some profound national healing was in order.

May continued her charmed path, as she appeared to receive Angela Merkel’s personal and political blessing and very obviously channelled Margaret Thatcher at her first Prime Minister’s Questions. Her rejection of an early general election was not held against her – even though she had condemned Gordon Brown for that very offence. The country, the consensus went, was fed up of voting. It was time to knuckle down and get on with the job.

In her subsequent statements, May pressed all the right buttons, not just for the Tory shires, but for at least some of those “left behind”. Her trademark statement “Brexit means Brexit” might have been gnomic to those preoccupied with small print, but for most people its meaning was clear: no more and no less than “We’re leaving”. The biggest criticism in the early days seemed to be that she spent too long on holiday in Switzerland, but even that was muted, as it gave the rest of the country permission for a break.

But is the benevolence starting to cool, and is such a cooling overdue? The retreat on delegating workers to boards is one small but emblematic example of hopes being raised, only to be dashed. The lack of follow-up on grammar schools (where elite and popular opinion are almost as profoundly split as over Brexit) might be another. And both seem to belong to a more general retreat, both in tone and in substance, away from the early sense of solidarity with the “little guy”. Where was May’s much-advertised support for those “just about managing” in her Chancellor’s first – and last – Autumn Statement anyway?

“Abroad” has been a particular failing. May’s attempts to drum up trade in far-flung places have not met with conspicuous success. Capping all, however, has been the Government’s almost ludicrously clumsy handling of Donald Trump’s victory in the US and the theatrical prominence of Nigel Farage.

We were told that the Prime Minister was well down the list for phone calls from the President-elect. But who was counting? We were told that May had an open invitation to the White House, “any time” she might be passing through, but this was soon eclipsed by news of an early invitation to the Trumps for a state visit and stay at Windsor Castle. When Trump mentioned Farage as a possible UK ambassador in Washington, rather than laughing it off in kind, the UK offered a po-faced riposte about there being no vacancy and insisted that our man in DC was doing a terrific job.

Whoever’s fault this was, none of it reflects well on the Prime Minister, who now has fences to mend, even as her attention needs to be focused on Brexit. Her initial economic and social messages have been watered down, leaving confusion about precisely what she stands for, and there is a harshness about some of her statements on social issues that suggests a lack of the political instinct that served Cameron so well.

If politics is about keeping all options open, she may yet succeed, and she certainly has courage. She stepped forward to be Prime Minister at a time of real peril. As Home Secretary, she stood up to her civil servants and had the guts to tell the truth to the Police Federation in public. She faced down Boris Johnson over water cannons for London, and then had the Machiavellian bravado to appoint him Foreign Secretary. That particular move has not yet played out to its conclusion, but she still holds all the cards.

But when you catch sight of Theresa May in an unguarded moment, or bereft of the preparation for which she is famed, it is hard not to see someone operating near the limits of her competence. And then you wonder: does Theresa May have what it takes to lead the UK out of the European Union while maximising the national interest and healing division? So far, the only response can be: if not May, then who? One day, though, that question could have an answer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks