Today, Venezuela. Tomorrow, anybody else who dares threaten US security

America’s dramatic seizure of a Venezuelan oil tanker by crack troops is deliberate show of its forceful new foreign policy, writes Mary Dejevsky: less global policeman, more policing its own hemisphere

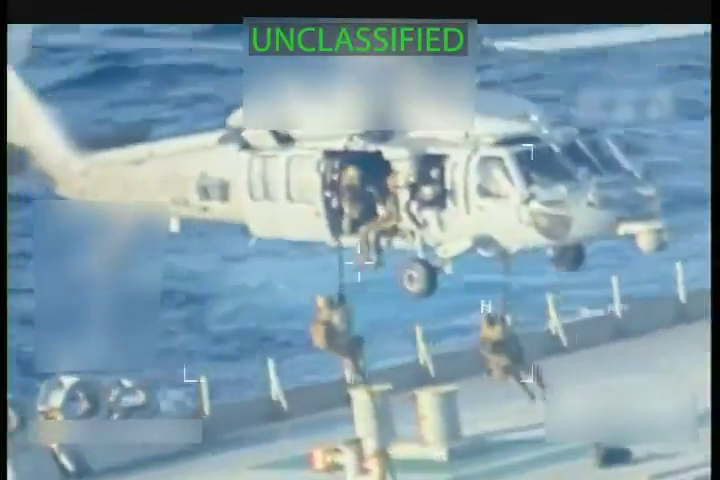

Donald Trump seemed as thrilled as a small child who has just taken another child’s toy, boasting that it was “the largest one ever seized”. Unfortunately, in this case, “it” was not a toy, but an oil tanker that was boarded and captured in a military-led operation seen by much of the Western world as piracy.

The tanker, the US attorney general said, was on a US sanctions list “due to its involvement in an illicit oil shipping network supporting foreign terrorist organizations” and it appears to have been en route from Venezuela to Cuba –although it is not clear whether it was fuel-starved Cuba, politically awkward Venezuela, or the tanker itself that was the primary target for the US. Any, or all, probably suits the Trump White House just fine.

How much further the US goes to exert its will over Venezuela remains to be seen. It has already sunk more than a dozen ships in the Caribbean Sea, claiming they were drug-running, and declared the country’s airspace closed. The ultimate measure would be for Trump to remove President Nicolas Maduro – seen as the illegitimate beneficiary of a rigged election – either by pressure or by force.

The risk here is that there seems to be little appetite for such drastic action among US voters, and a botched operation with less than a year to go before the US mid-term elections would be a far bigger liability for Trump and the Republican Party than leaving Maduro in place, where he could be politically useful as a poster-boy for external threats.

The US attacks on Venezuela and its interests might be seen as the first example of Trump’s second-term foreign policy in action, as it was set out in the US National Security Strategy document published last week. Understandably, what commanded most attention on this side of the Atlantic was the strategy’s undisguised contempt for the direction being taken, in this US view, by much of the European continent. One conclusion was that Europeans needed to look after their own security, rather than relying on the United States – something other US administrations have also argued, although with less urgency and bluntness.

Among the inferences drawn were that the United States was going to desert Europe, starting with Ukraine; that its security assurances could not be relied upon in future. The warning from Nato Secretary General, Marc Rutte, that “We /Europeans/ are Russia's next target” reflected, at least in part, the European defence establishment's panicked response.

If anything, though, it was what the document said about the United States and its future security policy that was the most arresting, in that it set out a vision that has been apparent for some time, but not articulated as a single idea.

What it boils down to is that the US intends to stop being the global policeman, for all Trump’s bragging about peace deals from Southeast Asia to central Africa to the Middle East. The US will give priority to its own security and that of its own Western hemisphere in a 21st-century version of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine.

All those peace deals Trump harps on about could be seen as an attempt to tie up loose ends and depart. That might explain the urgency behind Trump’s current efforts to end the war in Ukraine, and he still sees work to be done in the Middle East, but the overall message is: goodbye.

This leaves the Americas as the Trump administration’s security priority, which also helps to explain what he said in the first weeks of his second term about Greenland and Panama, as well as its current targeting of Venezuela. It would be consoling for the British and Europeans to regard this new US Security Strategy as unique to Trump. The hope would be that this Monroe Doctrine Mark 2 departs with Trump.

But, of course, this is not the first time in living memory that the US has intervened in Central and Southern America. Remember Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chile and, of course, Cuba. The British, above all, may also recall how hard it was to persuade our “special relation” to support the UK in its war with Argentina over the Falkland Islands, not to mention a certain unannounced US military intervention in (British) Grenada. Rather than being the exception, the US may be reverting to a very traditional type, with hemispheric power being what will drive future administrations. Could it be that the US defence presence in Europe is the exception, rather than its absence?

This is not to say that the exercise of hemispheric power will be plain sailing. How will the US deal with a rising Brazil or an uncooperative Canada? Where does China see the limits of its Pacific influence in the future? Even one hemisphere may be quite enough to keep the US busy, in peace and – if it sees this as necessary – in war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks