Yes, the junior doctors’ strike really is about money – how little Government is willing to spend on our health

The NHS is being funded on a wing and a prayer. The NHS is told to find £22bn of efficiency savings, yet there is no plan how to achieve them

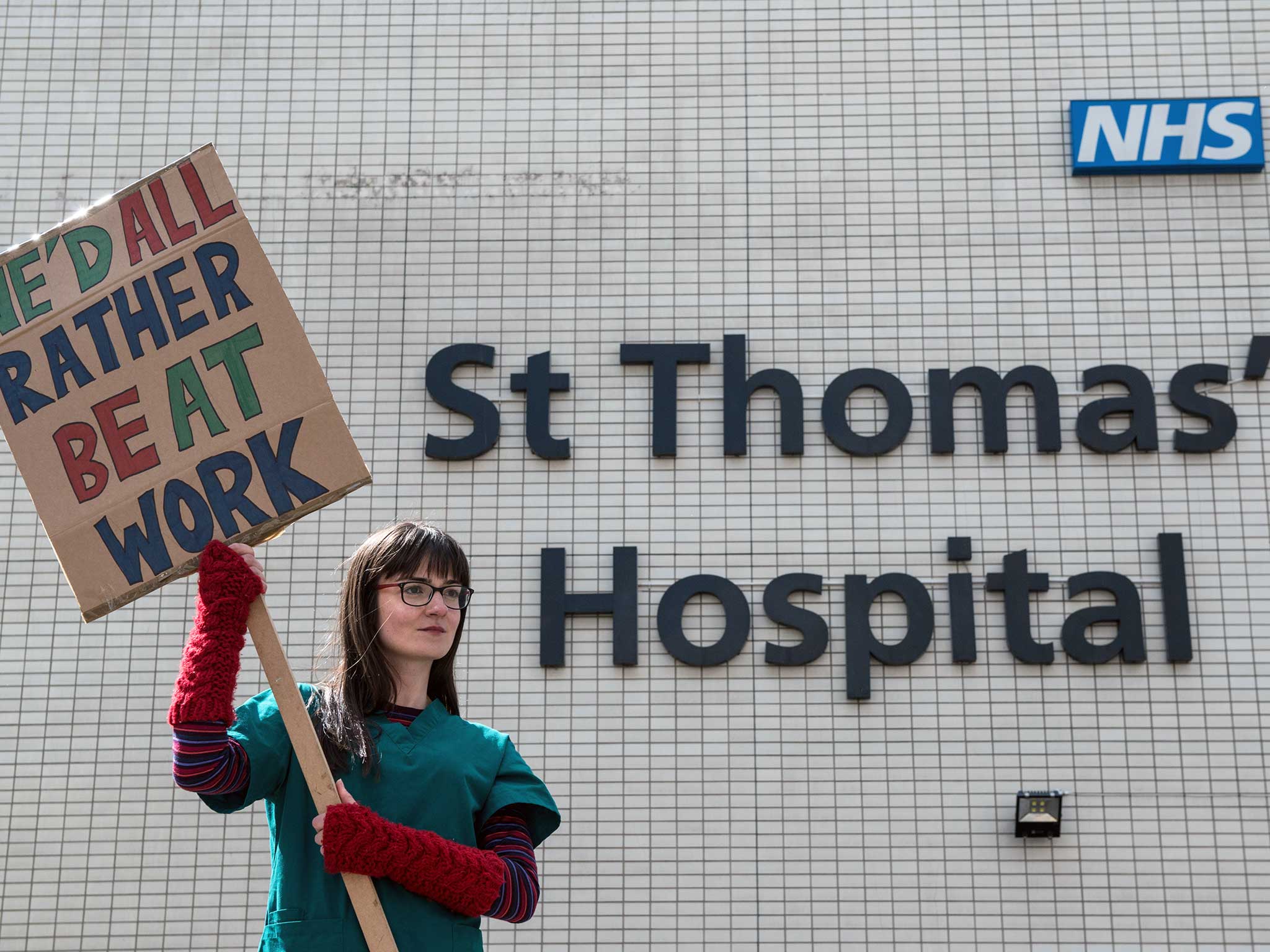

The strikes by junior doctors in England come down to money – but not, as ministers hint, because already well-paid medics seek to line their pockets further.

Nor are the striking doctors manning the picket lines out of revolutionary fervour like the 1980s miners, as suggested by Downing Street, which is clearly dictating the Government’s hard line in this dispute.

Wisely, Jeremy Hunt, the Health Secretary, has refused to demonise the doctors as latter day Arthur Scargills. It is obvious that many of them feel angry, overstretched and genuinely concerned about patient safety under the new contract being imposed upon them.

Yet after this week’s two day-long strikes, it is not easy to see where the British Medical Association (BMA) goes next. An indefinite strike, or stoppages at much shorter notice, would risk losing the public support the doctors still enjoy. The differences between the Government and the BMA are not as great as their rhetoric suggests, but neither side wants to back down.

The best course would be for an honest broker to resolve the main problem – pay for Saturday working. The broker could be one or more heads of the Royal Colleges, which did not endorse this week’s action. Some supported a sensible cross-party proposal to pilot the changes and an independent study of whether they would reduce weekend death rates. Hunt was wrong to dismiss as “opportunism” this Labour-led initiative, which could have averted the two strikes.

But the real money problem at the heart of the dispute is that the NHS is being funded on a wing and a prayer. The Government could have ensured that no junior doctor would be worse off under the contract, but it is trying to squeeze more juice out of an already crushed lemon. The NHS must find £22bn of efficiency savings by 2020-21 but, as yet, there is no plan how to achieve them.

Last month, some light was shone on how this magic number emerged. David Laws, the former Liberal Democrat Cabinet minister, wrote in his book about the Coalition Government that Simon Stevens, the chief executive of NHS England, estimated that it would need £15-16bn a year by 2020 just to maintain current standards in the health service. “You’ve got to be joking,” was Downing Street’s reaction, according to Laws.

So, under a revised plan, the estimated £30bn funding gap would be met by £8bn of extra funding and £22bn of efficiency savings – three times the long-running NHS average, requiring a continuing squeeze on pay that would lead to staff shortages.

NHS England denies it was “leant on”, insisting that different scenarios were modelled. But sometimes a story is so damaging that it has to be disputed. The Laws version has the ring of truth to it.

The Tory manifesto at last year’s election promised an extra £8bn and to bring in a “seven-day NHS”, which led to the new contract for junior doctors. But ministers have been slow to spell out how the seven-day pledge will be funded. Although the health budget will rise by £2bn in the current financial year, about half of that will be soaked up by extra pension costs and more will cover rising NHS deficits, leaving only a limited amount for changes such as seven-day working.

Front-loading the extra £8bn to the early years of this parliament was a necessary move but will only postpone an inevitable financial crisis for a couple of years. An under-funded social care system will put even more pressures on hospitals.

It is an open secret at Westminster that something’s gotta give. Even some senior Conservatives admit it. “We are going to have to revisit NHS funding,” one minister said.

The Blair Government pumped billions into the NHS to raise health spending to the European average. Now, as the NHS faces the toughest budget squeeze in its history, we are falling behind again.

Latest OECD figures show that the UK spends 8.5 per cent of GDP on public and private health care – 1.7 points less than the average of the 14 other countries who were in the EU before 10 new members joined in 2004, and 13th in the league table of 15.

Labour lifted the UK up the table thanks to a rare event – a popular tax rise, the 2002 increase in national insurance contributions by Gordon Brown, who earmarked the proceeds for health. It showed that people are prepared to pay for the NHS they want.

There is always a risk that extra cash is swallowed up by higher pay, as Labour discovered when it made a mess of a new GPs’ contract. But what is needed now is an NHS tax rise earmarked for frontline services.

Instinctively, David Cameron and George Osborne will be against it – as their reaction to Stevens’ original £15bn-£16bn estimate showed. They are committed to cutting taxes. But, after undermining their much-trumpeted ‘One Nation’ credentials since the election, a tax rise targeted at the better off to rescue the NHS would be the perfect way to restore them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks