A nuclear fallout shelter went untouched for 55 years. It might come in handy now

More than 100 people could shelter themselves from a nuclear apocalypse. The world outside, in this scenario? Annihilated

In the Kalorama neighbourhood of Washington DC, Smithsonian curator Frank Blazich puts on headlamp, checks his bag for a tape measure and descends into the sub-basement of Oyster-Adams intermediate school in search of the past.

“Oh, wow,” he says, coming to a metal door marked with a yellow and black pinwheel. “Look at that.”

Blazich had come because my colleague and I invited him. We’d become obsessed with talking about nuclear attacks and fallout shelters, and that’s what was on the other side of this door: an intact fallout shelter dating to 1962. A time capsule to a nation’s panic, lined up in a long, concrete hall.

“These were the water barrels,” Blazich says, pointing to a wall of 17.5-gallon drums labelled “Office of Civil Defense”. “Think five people per barrel, and we could get a rough approximation of who would be down here.”

We count: more than 100 people would have sheltered here to save themselves from nuclear apocalypse. The world outside, in this scenario? Annihilated.

“So, each person would get 10,000 calories for two weeks,” Blazich continues, blowing dust off a stack of tinned crackers. The crackers – “All Purpose Survival Biscuits” – would probably have been made of bulgur wheat, he explains.

When the pyramids of ancient Egypt were excavated, archaeologists discovered unspoiled bulgur wheat; Cold War scientists concluded that the stuff must be indestructible.

We’d become interested in this shelter for a few reasons. First, intact ones are rare; they were supposed to be dismantled in the 1970s. Second, North Korea’s Kim Jong-un is scary. He keeps surpassing predictions related to his nuclear arsenal – in September, he tested a weapon with seven times the yield of those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Recently a North Korean official said the country wouldn’t stop until its missiles could reach “all the way to the east coast of the mainland US”.

And third, the US President, a man not known for measured responses, has said that attacks would be met by “fire and fury like the world has never seen”, and has taken to calling Kim “Little Rocket Man”.

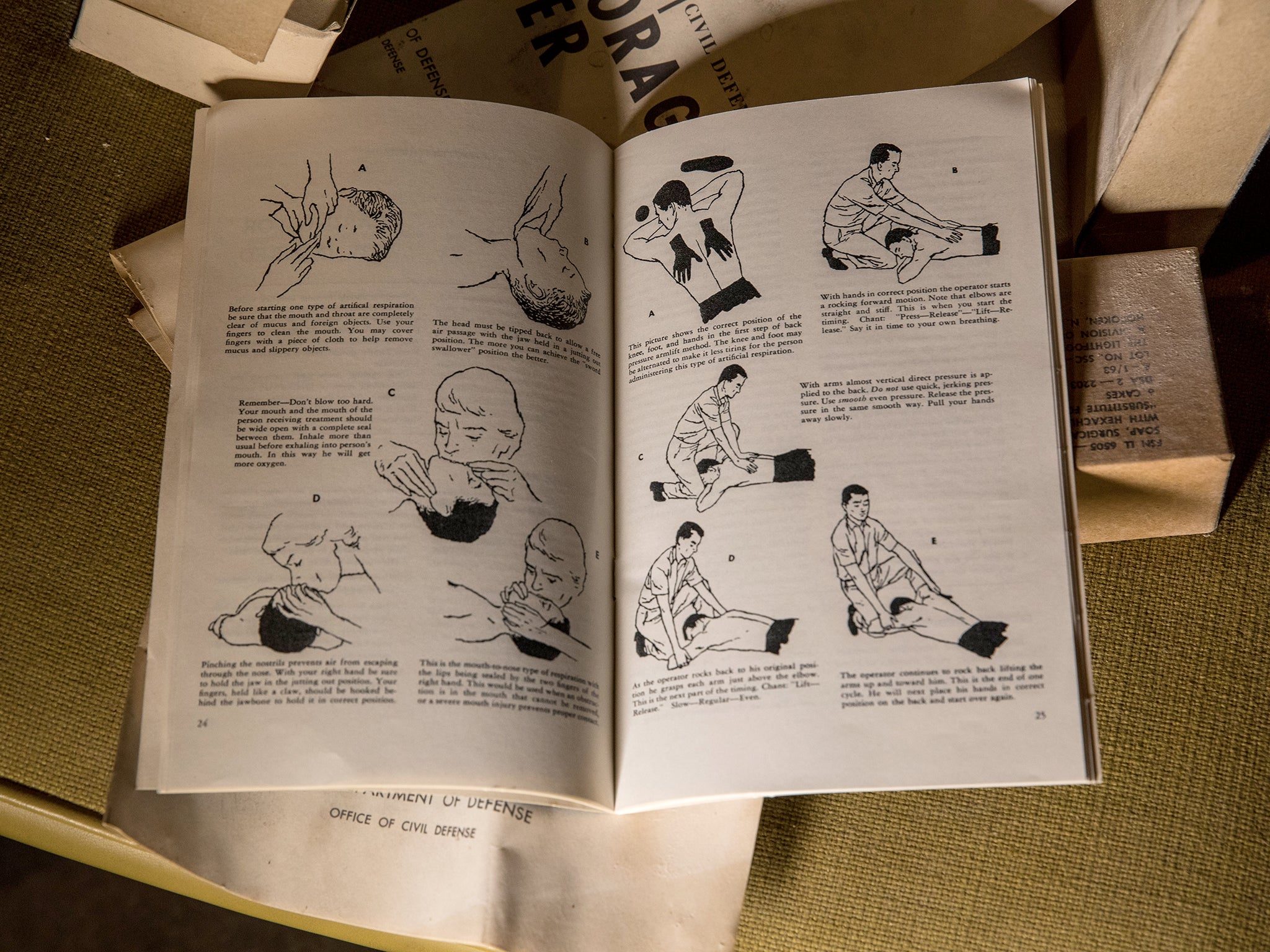

We find first-aid kits. Tongue depressors, cotton swabs. A yellowing pamphlet with instructions for treating everything from skin rashes to “sucking wounds in the chest”.

We find the latrines: barrel-shaped containers meant to be topped with a rubber seat. Blazich sits on one to make sure he’s assembled it correctly, then notices my colleague filming him. “You’ll have a video of me online,” he says, bursting into laughter. “The guy sitting on a 50-year-old toilet.”

Here we sit, on the fallout shelter toilet, because of the last reason we’re down here: 4) We want to solve a mystery: who this shelter was intended for, who the stuff belongs to now. We want to understand, in a grimly practical way, what it felt like the last time the country saw bunkers as a solution because we were all going to be blasted to holy hell.

What is a fallout shelter?

President John F Kennedy had a problem. It was 1961 and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was threatening to cut off access to West Berlin. “We do not want to fight, but we have fought before,” the President said in a July speech. He requested the government shell out $3.2bn in military spending – including $207m to identify spaces for fallout shelters. The United States could be bombed at any minute; shelters represented last-ditch hope for survival.

The money wasn’t enough to actually build shelters – it was up to volunteers to see through construction. Civilians would be defending themselves against nuclear war.

The District of Columbia took the lead, explains David Krugler, whose book, This Is Only a Test, tells the story of nuclear preparation in the nation’s capital. Churches and schools were surveyed. Basements were measured.

In offices, employees signed up as air-raid wardens, prepared to slap on armbands and shepherd co-workers to safety. In the food industry, companies produced shelter biscuits and “carbohydrate supplements” – fruit-flavoured candies to add flavour to confinement. Krugler tells us all of this, then says that we are not the only ones to have recently called him asking about nuclear warfare.

North Korea has everyone worried. The school spokeswoman says the same thing: Lots of people have been inquiring about the fallout shelter in Oyster-Adams – they had probably read the history-buff blogs we had, which catalogue possible shelter locations. And speaking of Oyster-Adams, here’s what we’ve learned so far: In the summer of 1962, a group of Washington DC schools were designated potential shelters. (Adams wasn’t on the initial list, but was added a few months later.)

“What is the civil defence using as an interpretation for this term ‘fallout shelter’?” asked a school board member, identified as Mrs Steele in meeting transcripts from September of that year.

A Mr Riecks explained: a fallout shelter was a place with a lot of radiation-resistant concrete between you and a nuclear bomb. “We have in our schools spaces for 28,000,” he said, citing a school called Macfarland, which could shelter 340. He noted, however, that Macfarland’s population was 1,300. The thousand students who couldn’t fit would just be taken to areas that were “as safe as possible.”

“Is there any basis for determining which 340 students go into those spaces?” a Mr Yorkelson wanted to know. “What is to prevent people in the street from rushing into the building and preempting the spaces assigned for children?” asked a Col Hamilton.

The short answer was, nothing. Nothing to determine which third of the student body got the shelter spaces, and nothing to keep the space from being swarmed. The short answer was that if there was a nuclear attack in the US capital, people would be flying by the seats of their pants.

Preparations for war that never came

But that, of course, was the subtext of what was happening in America in the era of fallout shelters. We wanted to know about our little shelter. What patriotic first-grade teacher had volunteered to be the air-raid warden at Oyster-Adams? What did fourth-graders remember about practice drills in the basement? How did the experience shape them, and when they looked at those walls of survival biscuits, did they see fear or salvation?

Our search for answers becomes a lesson in the slipperiness of history: When the fallout shelter was built, the elementary school was called John Quincy Adams. When it later merged with another school, all records of the previous incarnation were jettisoned. Seeking old yearbooks or class rosters, we visit the DC public school archives, digging through old newsletters and floor plans. Nothing.

The public-school archives lead us to a public-school warehouse, which lead us to the District’s city archives. Nothing. We reach out to the District’s Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency, which is what the Office of Civil Defence transformed into. Nothing. Someone recommends we try the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, but we don’t, because the odds seem slim. And because we are journalists, not Indiana Jones. And because it is beginning to feel a little weird for the two of us to take such fervent responsibility for a bunch of old barrels of water.

So there it is, an unsolved mystery. Biscuits, tongue depressors, latrine covers, thermometers and salt tablets, all meant for a nuclear war that never came. Nobody knows who they belong to, and nobody has any reason to take them away.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, we are at war’

We do find something else, though. Just when we had given up on our mystery, we find somewhere else to poke around. A different address. A different time capsule, but with the same kinds of memories.

While rifling through DCPS archives, we start to notice correspondence between the Office of Civil Defence and Gordon Junior High School in the Glover Park neighbourhood. In 1963 the school had a proposal. The only highly publicised trials in fallout shelters had been conducted on naval officers who, it could be argued, might not represent the average American. A Gordon teacher was proposing to place 62 students in the school’s shelter for a period of 36 hours to see how they made out. A roster was assembled.

The school had an illustrious student body, and some participants received notations: “Mother is Press Secretary to First Lady, Mrs. Johnson,” said one. “Father is US Representative Arnold Olsen, Montana.” There were children of Ethiopian and Indian diplomats, the son of a Turkish attache. A newspaper article was written about the proposed experiment, causing a minor uproar.

“Some of us believe that a shelter programme may be psychologically damaging,” read a letter to the editor signed by social workers and ministers. “It would tend to make nuclear war seem inevitable to children.”

Nevertheless, the experiment went forward. Participants assembled in the auditorium, greeted with seriousness by Principal J Dallas Shirley.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are at war,” he told them. “We are under threat of imminent attack.” The students filed down to a sub-basement none of them had known existed. They were divided into committees: sanitation, medical, food.

The shelter was filled with cots covered in paper blankets. “Like an olive-green paper,” remembers Christie Carpenter, the student whose mother was Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary.

“They made a lot of noise. My recollection is I didn’t sleep a wink.” Barry Truder remembers being assigned to the recreation committee and organizing an impromptu talent show. He invited people to make their own bingo cards.

They sang “Little Bunny Foo Foo” in a round. Verona Budke was placed on the communications team, staying in radio contact with the outside world, which came in the form of pretend news updates: A number of bombs had fallen in Washington, one told them. “There is great danger from radioactive fallout.” The night wore on. The students were told another group was seeking refuge – allowing them in would expose the students to radiation poisoning. But the other group contained children, they were told, so they voted to let them in.

The night wore on. One of the students, a boy whose father had been Kennedy’s assistant press secretary, started feeling lethargic. The communications team radioed the outside world; it was determined the boy had German measles.

They moved his cot to the other side of the room. Walter Combs was on the contamination committee, the group whose job it was to measure radiation levels in the shelter. He watched as his science teacher swung a Geiger counter around his head like a cowboy with a lariat, to capture the ambient air. Walter was in seventh grade. That year, he’d seen yellow megaphones rise above the Washington skyline, which would be used to tell the city when the Russians were bombing.

He’d sat through the Cuban missile crisis, when a social studies teacher said, “We are not going to have class today. We are just going to sit and look at each other because, depending on what happens, we might not ever see each other again.” Now, in the shelter, he watched his science teacher lassoing the air to see if it was poisonous, and he began to wonder whether it was all futile. What, after all, was the point? If this had been real and if the readings had been bad, what would they have done? Gone outside where the air was worse? There was no available treatment. There was only sitting below a school auditorium in a roomful of his 12- and 13-year-old classmates, and hoping the walls were thick enough.

And they weren’t. Or, they were, but not entirely. Or they were, but not as surveyors had intended or hoped for. The story of fallout shelters, it turns out, is partly a story about safety in the nuclear age, but it’s more about the placebo effect in times of panic. In a grimly practical way, the emotion of being inside one was a pleasant reassurance of self-deception.

Originally, when the government sent surveyors to find suitable shelter locations, they sought buildings that had a protection factor of 200, meaning that anyone in the shelter would be 200 times less exposed to radiation than a person outside, in the elements. But the surveyors didn’t find enough spaces, so the criterion were expanded: The fallout shelters at Gordon Junior High and Adams Elementary could have had a protection factor as low as 40, which might not have killed you, but it could have made you sick.

In many ways, Washington was the least sensible place to develop an extensive fallout shelter programme. Shelters were never designed to withstand bombs, only radiation aftermath. But in a dense, urban environment like Washington, it’s the bombs that would have killed people – quickly and before anyone could seek cover.

Shelters in a rural town would have greater lifesaving potential, but that was the catch-22: places where fallout shelters would have worked best were the places that nobody was likely to bomb. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the dismantling of the shelter programme began.

Attention was turned to safeguarding against natural disasters instead – preparations that seemed both more tangible and more likely needed. “The people who stayed really passionate about civil defence were laughed at by some; they were shrugged off by others,” says Krugler, the author.

There were other, smaller indignities in the fallout shelter programme. The “carbohydrate supplements”, meant to add a nutritional boost, were probably made with the red dye that was later banned because it was found to cause cancer. Frank Blazich, the Smithsonian curator, heard a rumour that after the quiet decommissioning of fallout shelters the carcinogenic fruit pebbles were sent to secretaries in government office buildings where they were then placed in candy bowls, to be eaten by the American public.

It was not clear what happened to the biscuits. Another mystery. Down in the subbasement of Oyster-Adams, we find a tin that had already been opened. Not 50 years ago, we assume, but more recently, by some other intrepid seeker of history. The bulgur crackers look like Saltines, and under Frank Blazich’s advice that they were probably still good, we try one. It tastes awful. Stale, mostly. It tastes like all the things we are afraid of, and all the things we do to convince ourselves that we are safe.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks