‘They’re asking for me to be murdered and I think that’s a bad idea’

Having gone into hiding after a fatwa on him was declared by Ayatollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of Iran, the author of ‘The Satanic Verses’ broke cover to defend himself

4 February 1990

After a year’s silence, Salman Rushdie today speaks out in defence of his novel The Satanic Verses. In a 7,000-word essay, written exclusively for The Independent on Sunday, he invites ‘‘ordinary, decent, fair-minded Muslims’’ to reconsider the book in an atmosphere of calm and reason.

Rushdie describes himself in his essay as ‘‘secular, pluralist, eclectic’’. He denies the charge of blasphemy, regrets the harm done to race relations over the past year, and expresses the hope that ‘‘the way forward might be found through mutual recognition of mutual pain’’.

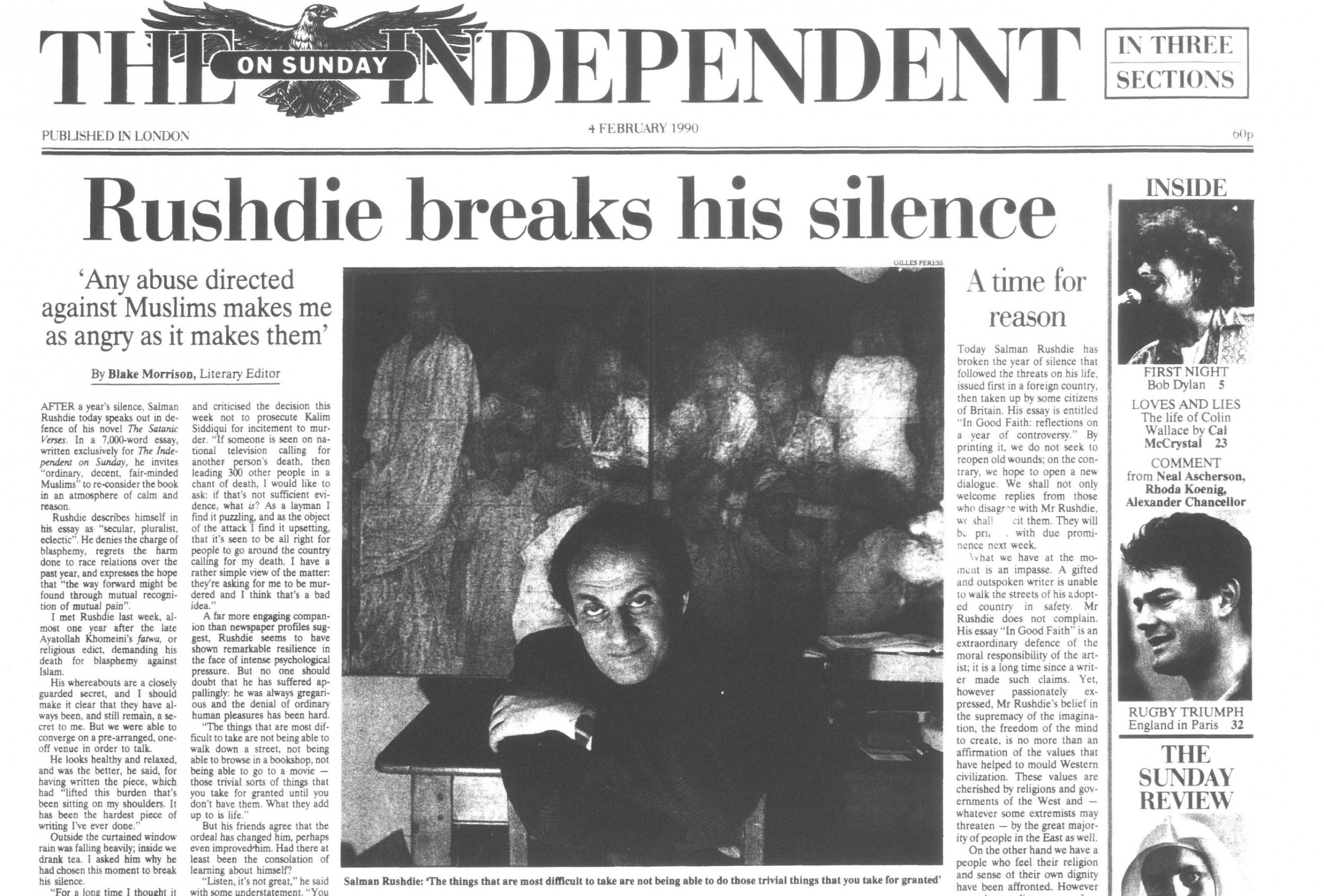

I met Rushdie last week, almost one year after the late Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa, or religious edict, demanding his death for blasphemy against Islam.

His whereabouts are a closely guarded secret, and I should make it clear that they have always been, and still remain, a secret to me. But we were able to converge on a pre-arranged, one- off venue in order to talk.

He looks healthy and relaxed, and was the better, he said, for having written the piece, which had ‘‘lifted this burden that’s been sitting on my shoulders. It has been the hardest piece of writing I’ve ever done.’’

Outside the curtained window rain was falling heavily; inside we drank tea. I asked him why he had chosen this moment to break his silence.

‘‘For a long time I thought it would be better for other people to take up the issue. And I also thought that in a way it might be eloquent to say nothing: here is someone whose business is language, now unable to speak. But I always knew there’d be a moment when people would be ready to listen again and though I’m hardly in a position to take a personal feel of what’s happening around the country, I began to think the moment had come.

‘‘I wanted to explain that with the events of the last year my responses have in many cases been very similar to those of the Muslim people attacking me: I’m horrified that the National Front could use my name as a way of taunting Asians and I wanted to make it clear: that’s not my team, they’re not my supporters.’’

But he is appalled by the violence of certain Muslims, too, and criticised the decision this week not to prosecute Kalim Siddiqui for incitement to murder. ‘‘If someone is seen on national television calling for another person’s death, then leading 300 other people in a chant of death, I would like to ask: if that’s not sufficient evidence, what is? As a layman I find it puzzling, and as the object of the attack I find it upsetting, that it’s seen to be all right for people to go around the country calling for my death. I have a rather simple view of the matter: they’re asking for me to be murdered and I think that’s a bad idea.’’

A far more engaging companion than newspaper profiles suggest, Rushdie seems to have shown remarkable resilience in the face of intense psychological pressure. But no one should doubt that he has suffered appallingly: he was always gregarious and the denial of ordinary human pleasures has been hard.

‘‘The things that are most difficult to take are not being able to walk down a street, not being able to browse in a bookshop, not being able to go to a movie - those trivial sorts of things that you take for granted until you don’t have them. What they add up to is life.’’

But his friends agree that the ordeal has changed him, perhaps even improved him. Had there at least been the consolation of learning about himself?

‘‘Listen, it’s not great,’’ he said with some understatement. ‘‘You make the best of the situation but it doesn’t mean it’s a positive experience. If you’d told me in advance this and this and this is going to happen over the next year I’d not have been very confident of my ability to cope with it. You don’t find out until you’re in the situation whether you can stand up to it. Fortunately, so far, I have. But I don’t recommend it. As a way of learning about yourself, there must be better ones.’’

He has worked. ‘‘Not in an ordinary way, and at times I could do nothing, but at the moment, touch wood, it’s going well. And there’s no doubt that when it is going well it’s easier to deal with the situation I’m in: only when a writer is writing does he feel like himself.’’ He has nearly finished a children’s book, is putting together a collection of essays, and has the synopsis for a novel, ‘‘one without any magic noses or cloven hooves’’ and not likely to be politically contentious: ‘‘But then I thought The Satanic Verses was a personal and inward novel, not a political one – obviously that’s not how it turned out. Some mistake, surely.’’

He has had novels with him to read and re-read: Moby Dick, Ulysses and Tristram Shandy above all. He has been reading poetry (‘‘Walcott, Milosz and a lot of American poetry: it puts you on your mettle as a novelist’’) and even writing it. He has also been reading – ‘‘for fairly obvious reasons’’ – writers of the 18th-century Enlightenment such as Rousseau, Diderot and Voltaire. ‘‘It’s very odd, when you think of how much has been written about them as the bedrock of European free speech, to see what actually happened to those guys in their lifetime. They were banned, persecuted, reviled and accused of blasphemy.’’

He admits to watching ‘‘a lot of junk television. I became hooked on a series called Capital City, about yuppie bankers, which was on when my other fixes – Dallas, Dynasty and Thirtysomething – were off the air. Having had a lot of late nights by myself I’ve also become an addict of American football.’’

Rushdie has been described as ‘‘obsessive’’ and ‘‘egomaniac’’. With me, he seemed rather keen to talk about things other than his work, not least the way the world he has been removed from has changed over the past year.

‘‘In normal circumstances, I’d have been on the first plane to Berlin and dancing on the Wall. I felt very envious of my friends who did go. I felt I’d missed one of the great moments of our time.

‘‘For week after week every item that led the news seemed to be good news - it was amazing. Those of us who were young in 1968 used to talk of that moment as some great shift in power towards the people. But actually nothing happened: a few kids ran down the street chased by the police! This time it actually did happen. And what’s optimistic about it is that those in power seem intelligent and restrained: it’s rather heartening to find that when people take over political control they’re far more reasonable than politicians.

‘‘To have a serious writer like Vaclav Havel running a country, quite possibly two serious writers running countries if Vargas Llosa wins the election in Peru, is a sign that perhaps the world is a less hopeless place than I thought it was. It would be nice if it happened here.’’ Did that mean he was still hostile to ‘‘Mrs Torture’’ Mrs Thatcher ? Hadn’t his attitude to the British state changed?

‘‘Yes. It’s very simple: if somebody takes steps to protect your life when it’s in great danger you feel more kindly towards them than you did before. So at a personal level my feelings towards the British government have changed, and that’s been assisted by the fact that the party I’ve supported and voted for all my life, the Labour Party, has been vocal in the attack on me, though there have also been incredibly supportive people like Michael Foot. Maybe I would use a different language for talking about the Conservatives now, and I make no apologies for that. I think better of the Tories for this trivial reason: they saved my life.’’

In recent weeks Paul Johnson, among others, has wondered why it is that Rushdie cannot now appear in public: can his life be in any more danger than Mrs Thatcher’s, for example? On Tuesday a lecture he has written on the connection between literature, politics and religion - but which does not allude explicitly to The Satanic Verses – will be delivered on his behalf by Harold Pinter at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. I asked him about the suggestion that he deliver it in person.

‘‘It crossed my mind, too, and if it were up to me I’d be there. But there are people I have to talk to about this, and it’s their judgement that I can’t be. I can reassure Paul Johnson that there is no one more anxious to resume my life than me. If I’m not doing so there’s a reason.’’

And one day ...?

‘‘I have to be optimistic about that because what’s the alternative: to be pessimistic, and that’s not much fun. When things seem appropriate they will happen.’’

He is a very strong, some have said arrogant person, and that conviction of his own worth has helped him to get through this experience. But had there been moments of doubt?

‘‘Every day, more than once – of course. But I’ve re-read the book - having to re-read one’s own work, a thing that all writers hate doing – and I honestly believe there isn’t a sentence I can’t justify. I’m happy to go through the book with anyone and talk about any page of it: that’s an open offer. But it’s difficult for such discussion to take place in an atmosphere of violence.’’

We said our goodbyes. As we parted I thought of all the things I would do over the rest of the day that he could not. His final words were: ‘‘I can defend my novel’s shape, the images it uses, the language it develops. That’s comparatively easy. What’s hard is to have to defend my life.’’

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies