Giovanni Battista Moroni, Royal Academy, preview: All hail to a dedicated follower of fashion

Britain's first full-scale exhibition of the 16th-century Italian painter reveals his work's psychological insight - as well as his eye for fashion

Shears in one hand, precious cloth in the other, the best-known tailor in art stares out at posterity.

Tightly buttoned into his padded ivory doublet and tied into his ballooning crimson hose, he looks up briefly from cutting a black fabric along a chalk line. The props of portraiture so often suggest intellect – books, letters, writing materials – or wealth – gold, jewels, fur – that Giovanni Battista Moroni’s portrait of a working man, even one in a trade that could yield considerable wealth, is radical indeed. And in examining Moroni’s life and work, the first full-scale exhibition in Britain dedicated to the 16th-century Italian painter will reveal an artist who achieved new levels of psychological insight in portraiture and bypassed convention, while apparently adhering to the traditions of his trade.

The Tailor, a portrait acquired at some cost in 1855 by the National Gallery, was the first Moroni in its now considerable collection of the artist’s work, and is on loan to the Royal Academy, where the show opens this week. In the Victorian era, the artist was immensely popular with the British and those, like Henry James, who adopted Britain as their home: George Eliot writes of the confident Grandcourt in Daniel Deronda that with “his well-cut features and exquisite long hands …. You might have imagined him a portrait by Moroni”.

Writers such as Eliot and James may have admired not only Moroni’s capacity to conjure depth and subtlety of character – as they aspired to do in print – but also the way he embodied, within his subjects’ sumptuous attire, an ideal of Italy as the home of style.

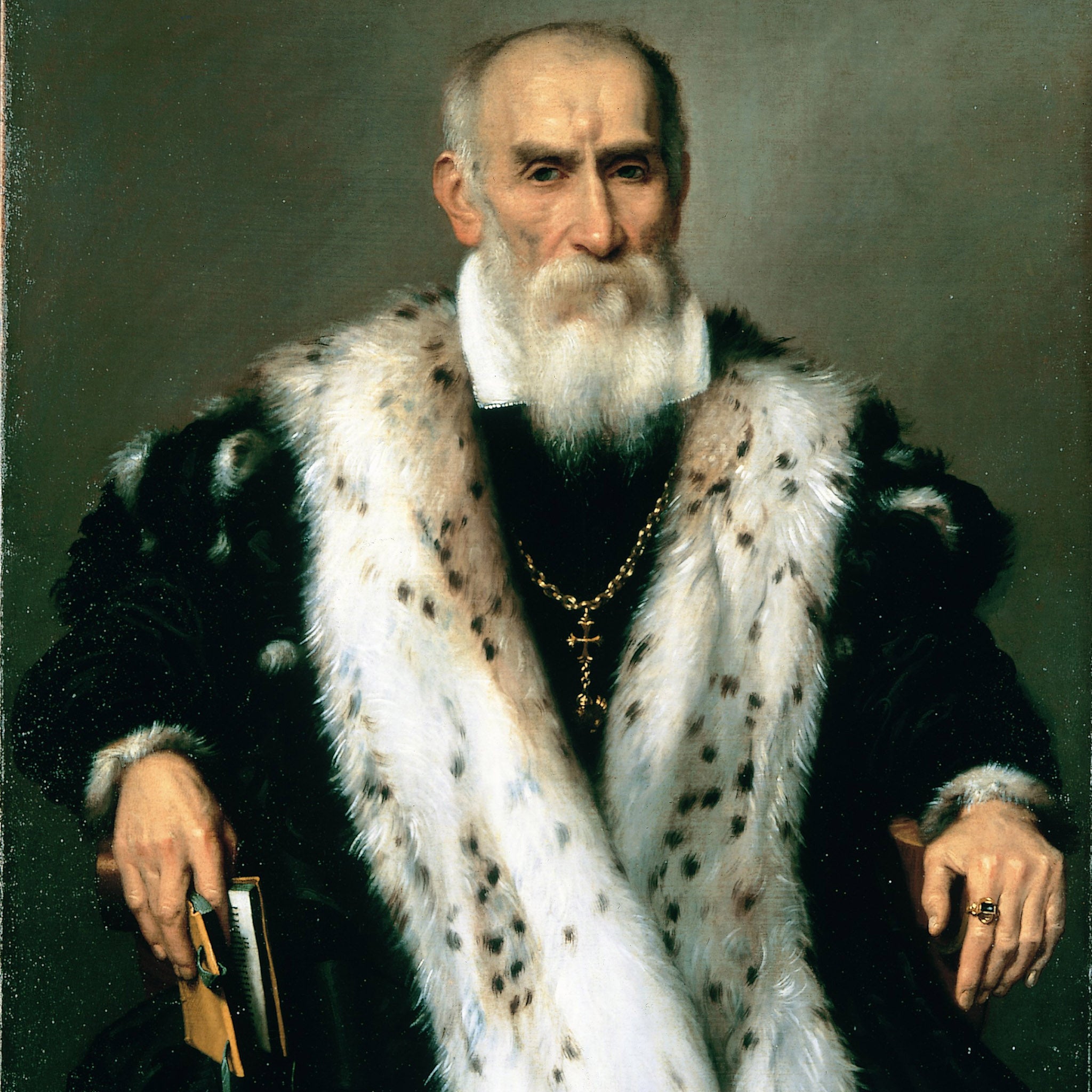

Moroni’s ability to suggest fur, brocade, velvet or lace is particularly masterful, and the rapidly changing fashion tastes of the 16th century can help art historians such as Arturo Galansino, who has co-curated the RA show, to date works. A turned-down, patterned collar, much like that of a modern shirt, dates a work to the 1550s; a small ruff, to the 1560s. The ruffs, picked out with tiny beads of white paint, grow bigger with each decade. Two different pictures of women from important families illustrate how quickly necklines change: the wide one on Isotta Brembati’s green-and-gold brocade dress in her 1555 portrait is overtaken by the high-necked, open bodice of a lady thought to be Luciana Albani Avogadro in a painting dated between 1556 and 1560. Both were poets, but, unlike male sitters, they are accessorised not with volumes of verse, but with showy fans. Brembati would later marry the widower known in his own portrait as The Man in Pink (1560), every inch of his costume as roseate as his cheeks.

Fashion historian Jane Bridgeman can help us decode such outfits. She dispels a commonly held theory that the fashion for black seen in Moroni’s work was wholly influenced by Philip II of Spain, often in mourning. Black was, rather, the uniform of the Venetian Republic, within which were the painter’s home town, Albino, and nearby early workplace, Bergamo. Venice’s citizens were obliged to wear a black robe, a forerunner of our academic gown, over their more flamboyant indoor clothes.

“Clothing in the 16th century has to reflect a person’s status,” says Dr Bridgeman. “You cannot go out wearing something extremely expensive if you are a carpenter. The cut is the same for everyone, more or less, and a lot of people wore fourth-, fifth- or sixth-hand clothing. But the difference is in the fabric.” A skilled craftsman like the handsome Tailor would extend the life of a garment with alterations, for decades. Sleeves and collars would be re-fashioned: Moroni’s earlier sitters have voluminous, ballooning sleeves that narrow over the years until Isotta Brembati, for example, has just a little puff sleeve below the shoulder. Isotta has overdone it a little, with her gold-muzzled sable, ornate cross, bracelets on both wrists and ribboned earrings. She is, says Dr Bridgeman, a little provincial.

For Moroni’s male subjects, getting dressed was complicated. There was always the doublet, at one stage wadded to give the wearer a strangely paunchy bow-shape – the Tailor opts for this himself. Then below, gigantic pumpkin-like trunk-hose would be worn with drainpipe, cuff-like, cannions. Elaborately constructed and tied on, the ensemble was finished off with a codpiece to mask the fussy closures. Only with time did the codpiece become ostentatious and explicit. A sword, for show, was a fantastically expensive item. The whole get-up was deeply impractical. Dr Bridgeman likens such fashions to a pair of six-inch Jimmy Choos: “You’re not walking anywhere – you’re falling in and out of cabs.”

Like the Elizabethans, Italian men copied the trend set by mercenaries who slashed their own robust garments; then they, and women too, pulled their silk undergarments through the slits – until it became fashionable to fake this, by stitching little billows of silk directly into the outer garment. Like today’s designer-ripped jeans, this distressed affectation cost more than the regular article. But one of the costliest items in the wardrobe was a seasonal lining of lynx, sewn into the outer garment for warmth every winter by a furrier, and detached each spring. It typically cost a year’s wages.

Even Moroni’s name derives from the Italian word for mulberry, whose leaves fattened the millions of silkworms needed to meet the demands of the fashion-conscious. Bergamo is still a centre for working silk, although much is today imported from China and finished in Italy. The son of a stonemason, Moroni was taught by a now little-known 16th-century painter, Alessandro Bonvicino, known as Moretto, who was referred to as “the Raphael of Brescia”. The contemporary chronicler of art and artists, Giorgio Vasari, marvelled at the skill of Moretto, who “took great pleasure in simulating cloth of gold or silver, velvet damask and other fabrics of all kinds”.

It suited Moroni, who used no assistants, to work in the last years of his life in his Albino home, away from spotlit Venice and Florence, and it is arguably this decision that has denied him a place in the big league. The Royal Academy show sets out to acknowledge his special gift. “You see other artists who are brilliant at clothes, but their portraits are not very good,” says Dr Bridgeman. “With Moroni, we notice the garments, but they do not get in the way of the subject.”

‘Giovanni Battista Moroni’ is at the Royal Academy from Sat to 25 Jan (royalacademy.org.uk),

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks